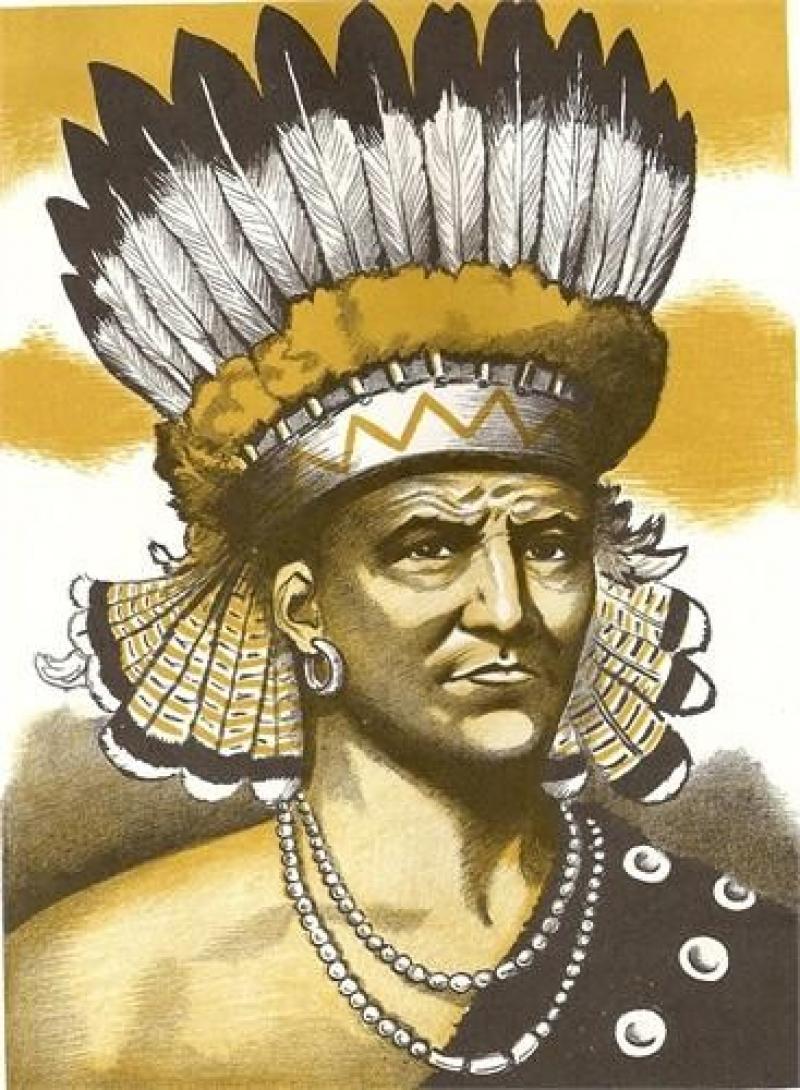

Echoes in the Wilderness: Chief Powhatan and the Enduring Legends of America

America is a nation woven from stories, a vibrant tapestry of myths, histories, and folklore that stretches from the primordial whispers of indigenous creation to the digital age’s urban legends. These narratives, often blurring the lines between fact and fiction, are more than mere entertainment; they are the bedrock of a collective identity, shaping our understanding of who we are and where we come from. Among these foundational tales, few figures loom as large, or are as profoundly misunderstood, as Chief Powhatan, the paramount leader whose powerful confederacy stood as the initial, formidable barrier to English colonial ambition in the early 17th century. His story, intertwined with the very genesis of Anglo-America, offers a unique lens through which to examine the enduring power and complexities of American legends.

The American mythological landscape is as diverse as its people. It encompasses the cosmic journeys of Native American trickster gods, the Puritan struggles against wilderness and perceived witchcraft, the towering feats of frontier heroes like Paul Bunyan and Pecos Bill, the rebellious spirit of pirates and outlaws, and the quiet dignity of everyday people who carved out lives against immense odds. Yet, before the axes of loggers echoed in the forests or the steam whistles of trains pierced the plains, the land was alive with the legends of its first inhabitants. These were oral traditions, rich with ecological wisdom, spiritual insight, and detailed histories passed down through generations. The arrival of Europeans, however, irrevocably altered this narrative, injecting new characters, conflicts, and ultimately, new myths into the continent’s unfolding saga.

At the heart of this collision of worlds lies the figure of Wahunsenacawh, known to the English as Chief Powhatan. He was not merely a tribal chief but the mamanatowick, the paramount leader of an intricate political and economic confederacy of Algonquian-speaking tribes inhabiting Tsenacommacah, a vast territory stretching across much of present-day eastern Virginia. By the time the English arrived at Jamestown in 1607, Powhatan had consolidated power over some 30 distinct tribal groups, commanding a population estimated at around 15,000. His capital, Werowocomoco, located on the York River, was a bustling hub of diplomacy, trade, and cultural life.

The English, desperate and ill-prepared, found themselves in the shadow of this sophisticated indigenous empire. Their early accounts, often self-serving and biased, nevertheless paint a picture of a leader of immense authority and strategic acumen. Captain John Smith, perhaps Powhatan’s most famous (and self-aggrandizing) interlocutor, described him as "a tall, well proportioned man, with a severe aspect, his hair very gray, and a thin beard… of a strong and able body." Smith’s narratives, particularly his famous "rescue" by Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas, became one of the foundational legends of America, shaping perceptions of Native Americans for centuries.

This legend, however, is deeply problematic. The romanticized image of Pocahontas, forever saving the dashing Englishman, overshadows the harsh realities of colonial encounter and distorts Powhatan’s role. Many historians now believe Smith’s "rescue" was either a ritualistic adoption ceremony meant to assert Powhatan’s dominance over Smith, or an embellishment by Smith himself, designed to elevate his own heroic status. Regardless, the tale has endured, becoming a powerful symbol of reconciliation and "first contact," even as it whitewashes the violence and exploitation that followed.

Powhatan, far from being a simple tribal elder, was a shrewd and pragmatic leader facing an unprecedented challenge. He initially viewed the English not as an existential threat, but as another tributary group to be absorbed or managed within his extensive network. He sought to control their movements, leverage their technology (especially their metal tools and weapons), and understand their intentions. He offered them food when they starved, hoping to incorporate them into his sphere of influence. But as the English numbers grew and their demands escalated, Powhatan’s strategy shifted from wary hospitality to calculated resistance.

One of the most compelling insights into Powhatan’s mind comes from an exchange recorded by John Smith, likely in 1609. Frustrated by the constant English demands and their encroaching presence, Powhatan is said to have delivered a powerful speech to Smith, questioning the futility of their conflict:

"I am now grown old, and must soon die; and the succession must descend to my brothers, Opitchapam, Opechancanough, and Kekataugh, and then to my two sisters, and their two daughters. I wish also to enjoy some rest, and ere I die, peaceably to leave my rich possessions to my kindred, for whom I have taken so much pains and adventure. Do you think I am so simple, as not to know it is better to eat good meat, lie well, and sleep quietly with my women and children, laugh and be merry with my English, and trade for their copper and hatchets, than to run away from them, and lie cold in the woods, feed upon acorns, roots, and such trash, and be so hunted by you, that I can neither rest, eat, nor sleep? In this way, my women and children are dying of cold and hunger. Indeed, your chief desire is to be in what I possess, but for that, it is not possible to agree. For you are always sending your men to invade my people, to take our corn, our land, and to destroy our houses. Why should you take by force that which you may have by love? Why should you destroy us, who have provided you with food? What can you get by war?…"

While this speech is mediated through Smith’s own interpretation and potential embellishment, it nevertheless captures the profound wisdom and weary pragmatism of a leader trying to protect his people and culture from an overwhelming, alien force. It speaks to a desire for peace and trade, undercut by a clear understanding of the English hunger for land and resources. This quote, whether precisely accurate or a reflection of the sentiment, has become a legendary utterance, symbolizing the indigenous plea for understanding and coexistence in the face of colonial expansion.

Powhatan’s death in 1618 marked a turning point. Without his unifying leadership, the confederacy gradually fractured, though his successor, Opechancanough, mounted formidable resistance in the Great Massacres of 1622 and 1644. Ultimately, the relentless pressure of English expansion, disease, and superior weaponry proved insurmountable. The Powhatan Confederacy, once a vibrant indigenous empire, was reduced to a scattering of reservations, its people dispossessed and its culture marginalized.

Yet, the legend of Chief Powhatan endures. He represents not just a historical figure, but a powerful symbol of indigenous sovereignty, resilience, and the tragic consequences of colonial encounter. His story, alongside that of Pocahontas, became part of the broader American narrative, often simplified and distorted to fit a specific national mythology – one that emphasized the "discovery" of a "new world," the taming of a "wilderness," and the "progress" of European civilization.

Beyond Powhatan, other American legends serve similar functions, shaping and reflecting the nation’s evolving identity. The Pilgrim Fathers landing at Plymouth Rock embodies the narrative of religious freedom and steadfast faith. The Salem Witch Trials, a dark chapter, morphed into a cautionary tale about hysteria and conformity. The figures of the American Revolution – Washington, Jefferson, Franklin – are elevated to demigods, their lives imbued with an almost divine purpose to forge a new nation. Later, the rugged individualism of the frontier, embodied by figures like Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, became central to the American psyche, celebrating self-reliance and the spirit of exploration. Even the tall tales of Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed, though overtly fictional, speak to the American ideal of conquering nature and spreading bounty.

What ties these diverse legends together is their capacity to instruct, inspire, and occasionally, obscure. They are the collective dreams and anxieties of a nation, reflecting its values, its aspirations, and its often-unresolved tensions. The legend of Chief Powhatan, in particular, forces us to confront the complex and often painful origins of America. It reminds us that the "new world" was ancient and inhabited, that its first leaders were powerful and wise, and that the stories we tell about our beginnings profoundly impact our understanding of the present.

In a modern America grappling with its past, re-examining these legends is not just an academic exercise; it’s a vital step towards a more complete and honest national self-understanding. By critically engaging with the myths surrounding Chief Powhatan and other foundational figures, by peeling back the layers of romanticism and bias, we can uncover the deeper truths about the collision of cultures, the struggle for land and power, and the enduring legacies of both triumph and tragedy. The echoes of Powhatan’s wisdom, his strategic brilliance, and his ultimate loss continue to resonate in the American wilderness, inviting us to listen more closely to the diverse voices that have shaped, and continue to shape, the legends of this complex nation.