Okay, here is a 1200-word article in a journalistic style about the Battle of Connell’s Prairie, Washington, framing it within the broader legends of America.

The Echoes of a Forgotten Fight: Connell’s Prairie and the Unwritten Legends of America

America is a nation built on legends – tales of pioneers, daring explorers, and monumental battles that forged its identity. Yet, beneath the familiar narratives lie countless forgotten skirmishes, pivotal moments brushed aside by the relentless march of time and selective memory. One such chapter, rich in human drama, injustice, and the clash of civilizations, unfolded on a crisp autumn day in 1855, in a quiet clearing then known as Connell’s Prairie in what would become Washington Territory. This isn’t a legend of triumph, but a potent, unvarnished story that speaks volumes about the true cost of westward expansion and the enduring spirit of resistance.

The Battle of Connell’s Prairie, a brutal ambush by Native American warriors led by the legendary Nisqually Chief Leschi, against a detachment of U.S. Army regulars and volunteers, serves as a stark reminder that many American legends are not of clear-cut heroes and villains, but of complex figures caught in the unforgiving currents of history. It’s a story that encapsulates the broader Puget Sound War, a tragic conflict often overshadowed by its more famous counterparts, yet one that carved deep and lasting scars into the landscape and the collective memory of the Pacific Northwest.

The Looming Storm: Manifest Destiny’s Darker Side

By the mid-19th century, the concept of Manifest Destiny, the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand across the continent, was in full swing. Gold rushes, land speculation, and a burgeoning settler population pushed relentlessly westward, colliding with the established cultures and ancestral lands of Indigenous peoples. Washington Territory, newly formed in 1853, became a flashpoint. Its first governor, Isaac Stevens, a man of relentless ambition and a former military engineer, was tasked with both surveying the new territory for a transcontinental railroad and, crucially, negotiating treaties with the numerous Native tribes to clear the way for settlement.

Stevens’ treaty councils, held with haste and often under duress, became a primary catalyst for the coming war. Tribes were presented with documents they often didn’t fully understand, translated by interpreters who sometimes distorted the terms, and pressured to cede vast tracts of land for meager compensation and relocation to reservations far from their traditional hunting and fishing grounds. The Medicine Creek Treaty of 1854, which affected Chief Leschi’s Nisqually and allied tribes, was particularly egregious. It assigned them a small, rocky reservation unsuitable for their way of life, an insult that Leschi found impossible to accept.

"The paper you ask me to sign is not good," Leschi reportedly told Stevens, encapsulating the deep distrust that permeated the negotiations. "It is not for us to live upon. My people will die there." This refusal, born of a deep connection to his land and a clear-eyed understanding of the treaty’s implications, set him on a collision course with the territorial government.

Leschi: From Negotiator to Reluctant Warrior

Leschi, born around 1808, was not initially a warmonger. He had served as a guide for early settlers and maintained cordial relations with many pioneers. However, the blatant disregard for Native rights and the imposition of unsustainable terms in the treaties transformed him. He became a unifying figure, appealing to the Nisqually, Puyallup, Muckleshoot, and Klickitat tribes to resist the encroachment. For many Native people, Leschi represented a last hope for preserving their way of life. For the settlers, he became a symbol of defiance, a "hostile" chief who threatened their progress and security.

As tensions mounted in the summer and fall of 1855, isolated incidents escalated into open conflict. Settlers, increasingly fearful, formed volunteer militias. Native communities, seeing their lands shrinking and their way of life threatened, prepared for defense. The Yakama War had already erupted east of the Cascades, and its ripples soon spread to the Puget Sound. Governor Stevens, returning from the east, found the territory in a state of near-panic. He declared martial law in certain areas, fueling further resentment and solidifying Leschi’s resolve.

The Ambush at Connell’s Prairie: October 27, 1855

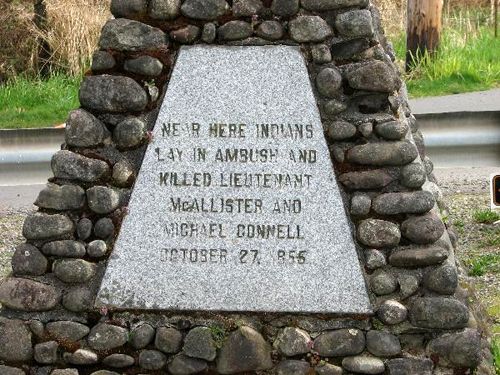

The stage was set for confrontation. On October 27, 1855, a combined force of U.S. Army regulars from Fort Steilacoom and local volunteers, numbering around 100 men, were on patrol, attempting to locate and engage Leschi’s forces. Under the command of Lieutenant William A. Slaughter, a young, ambitious officer, they pushed through the dense, unforgiving wilderness of the Puyallup River Valley.

Leschi, a master of the terrain, knew this country intimately. He understood the advantages of the thick forest, the ravines, and the limited visibility. He strategically positioned his warriors – likely numbering between 100 and 150, many armed with muskets, bows, and knives – along a narrow trail at Connell’s Prairie, a small clearing surrounded by a tangle of brush and ancient trees. It was a classic ambush site, chosen with deadly precision.

As Slaughter’s column advanced, unsuspecting, they entered the kill zone. The Native warriors, hidden and silent, waited until the U.S. forces were fully committed. Then, with a sudden, deafening volley of gunfire and war cries, they sprang their trap. The attack was swift, fierce, and chaotic. Soldiers and volunteers, caught completely by surprise, scattered amidst the trees, struggling to return fire against an unseen enemy.

Lieutenant Slaughter, reportedly rallying his men, was among the first to fall, struck down by a bullet to the chest. His death sent a shockwave through the ranks. Several other soldiers and volunteers were killed or wounded in the initial minutes. The engagement was a close-quarters, brutal affair, with both sides fighting desperately in the undergrowth. The U.S. forces, disoriented and leaderless, were forced to retreat, leaving their dead and wounded behind.

While the Native forces also suffered casualties, the Battle of Connell’s Prairie was a significant tactical victory for Leschi. He had demonstrated that his warriors were organized, determined, and capable of inflicting serious damage on the better-armed U.S. military. It boosted Native morale and signaled that the conflict would be far from an easy conquest for the settlers.

Aftermath and the Escalation of War

The defeat at Connell’s Prairie sent ripples of fear and outrage through the fledgling settler communities. News of Slaughter’s death and the ambush fueled demands for harsher action against the Native tribes. The battle solidified the perception of Leschi as a dangerous adversary and intensified the pursuit of him and his followers.

The Puget Sound War raged on for several more months, characterized by skirmishes, raids, and the construction of blockhouses by settlers for defense. Governor Stevens, increasingly autocratic, suspended civil law and pursued a policy of aggressive military action. The war was brutal for both sides, leading to significant loss of life, displacement, and immense suffering.

Leschi’s Tragic Legend: Justice Denied and Later Restored

The legend of Connell’s Prairie, however, doesn’t end on the battlefield. It extends to the tragic fate of Chief Leschi himself. After months of evading capture, he was eventually betrayed and arrested in 1856. He was charged with the murder of Lieutenant Slaughter, an act committed during a legitimate act of war.

Leschi’s trial became a legal and moral battleground. Two juries failed to convict him, recognizing the inherent injustice of prosecuting a combatant for acts committed in war. However, a third trial, heavily influenced by political pressure and public sentiment, ultimately found him guilty. Despite pleas for clemency from many, including some of the settlers who knew and respected him, Governor Stevens refused to intervene. On February 19, 1858, Leschi was hanged near what is now Fort Steilacoom. His last words, according to some accounts, included a declaration of his innocence, stating he was "no murderer" and that he had only "defended his people."

Leschi’s execution sparked outrage among many at the time and continued to be a source of shame and debate for generations. He became a martyr for Native American rights and a symbol of the injustices perpetrated during the era of westward expansion.

In a remarkable act of historical redress, nearly 150 years later, in December 2004, a special historical court convened by the State of Washington, comprised of three state Supreme Court justices, officially exonerated Chief Leschi. The court found that he had been "unlawfully hanged" and that he was "a prisoner of war, lawfully defending his people." This landmark decision acknowledged the fundamental injustice of his trial and execution, finally recognizing Leschi not as a criminal, but as a warrior and a leader who fought for his people’s survival.

The Enduring Echoes

Today, Connell’s Prairie is no longer a wilderness ambush site but a patchwork of suburban developments and agricultural land near the modern cities of Sumner and Puyallup. There are no grand monuments to the battle, no towering statues commemorating the fallen on either side. Yet, the legend of Connell’s Prairie persists, whispered in the oral histories of the Nisqually and Puyallup tribes, studied by local historians, and slowly being reclaimed as a vital part of Washington’s, and America’s, story.

This forgotten battle and the subsequent injustice of Leschi’s trial and execution serve as a powerful counter-narrative to the simplistic legends of conquest. They remind us that the expansion of the United States was a deeply complex, often violent process, marked by profound cultural clashes and tragic consequences for Indigenous peoples.

The story of Connell’s Prairie is a legend of America not of glorious victory, but of a desperate fight for survival, of a leader who chose resistance over submission, and of a nation grappling with the darker chapters of its past. It’s a legend that compels us to look beyond the surface, to understand the nuanced truths, and to remember that the voices of the vanquished also have a vital place in the grand tapestry of American history. Only by acknowledging these difficult truths can we truly understand the foundations upon which this nation was built and move toward a more complete and just reckoning with our past.