The Unsung Architect: Alexander Culbertson and the Real Legends of America

America is a nation built on legends, a vast tapestry woven from the daring exploits of frontiersmen, the enduring spirit of pioneers, and the larger-than-life figures of folklore. From Paul Bunyan’s colossal axe strokes shaping the landscape to Davy Crockett’s legendary bear hunts, these tales capture the essence of a nation perpetually reinventing itself, pushing boundaries, and forging an identity in the crucible of the wilderness. Yet, beneath the shimmering surface of these popular myths lies a deeper, more profound layer of legend – the stories of real men and women whose lives, though often less romanticized, profoundly shaped the continent and its burgeoning identity. Among these, the figure of Alexander Culbertson, a towering figure in the 19th-century fur trade, emerges not as a mythical hero, but as an authentic architect of the American West, whose pragmatic diplomacy, daring enterprise, and complex relationships created a legend far more intricate and enduring than any tall tale.

The "legends of America" are not solely confined to the realm of the fantastic. They are also etched into the very soil, in the pathways blazed by explorers, the settlements carved from forests, and the arduous journeys undertaken in pursuit of destiny. This grand narrative, often dubbed "Manifest Destiny," was not merely an abstract concept; it was enacted by individuals, driven by ambition, necessity, and a relentless will to expand. While figures like Kit Carson and Daniel Boone often dominate the popular imagination, their legends are often simplified, distilled into archetypes of rugged individualism. Culbertson’s story, however, offers a more nuanced and compelling insight into the true mechanics of frontier expansion, presenting a legend of adaptation, negotiation, and the often-uncomfortable bridging of disparate worlds.

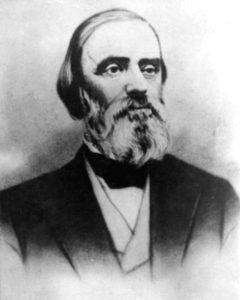

Born in 1809 in Pennsylvania, Alexander Culbertson was not destined for the quiet life of an eastern farmer. Drawn by the irresistible pull of the western frontier, he ventured into the vast, untamed territories of the Upper Missouri River in 1833. Here, in the heart of what was then a contested wilderness, he would spend over three decades, rising through the ranks of the powerful American Fur Company to become one of its most influential figures. His domain was Fort Union, often called the "Kingdom of the Upper Missouri," a bustling nexus of trade and diplomacy nestled at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers. This was not merely a trading post; it was a strategic outpost, a cultural crossroads, and a symbol of American commercial reach deep into Native American lands.

Culbertson’s legend is rooted in his extraordinary ability to navigate this complex, multi-cultural landscape. Unlike many of his contemporaries who viewed Native Americans with hostility or condescension, Culbertson understood that survival and prosperity in the fur trade depended entirely on forging strong, reciprocal relationships with the indigenous tribes. He quickly mastered several Native American languages, including Blackfeet, Crow, and Hidatsa, transforming himself into an indispensable interpreter and diplomat. This linguistic prowess, combined with a keen understanding of Native American customs and protocols, earned him respect and trust among powerful chiefs, a crucial asset in an environment where misunderstanding could quickly escalate to conflict.

His most enduring personal connection was his marriage to Natawista (also known as Medicine Snake Woman), the daughter of a powerful Blackfeet chief. This wasn’t merely a romantic union; it was a strategic alliance, a common practice among fur traders to cement commercial and diplomatic ties. Yet, their marriage transcended pure utility, reportedly becoming a relationship of genuine affection and mutual respect. Natawista, a woman of intelligence and grace, played a vital role in Culbertson’s success, offering him insights into tribal politics and facilitating his access to the vast Blackfeet hunting grounds, a primary source of the valuable buffalo robes that became the backbone of the later fur trade. Their union symbolized the complex, often intimate intermingling of cultures that characterized the frontier, a stark contrast to the later narratives of unyielding conflict.

"Culbertson truly understood that the economic lifeblood of the fur trade flowed through the trust he built with the Native American nations," observed historian David J. Wishart in his seminal work on the American Fur Company. "He wasn’t just buying pelts; he was managing an empire built on relationships, an empire where diplomacy was as vital as firepower."

At Fort Union, Culbertson presided over a vibrant, polyglot community. Goods from St. Louis – guns, blankets, beads, alcohol – were exchanged for beaver pelts and buffalo robes from the Blackfeet, Crow, Assiniboine, and Hidatsa. The fort was a hub of activity, a stage where traders, trappers, Native American hunters, and curious travelers like George Catlin and John James Audubon converged. Culbertson, with his imposing stature and commanding presence, was the undisputed master of this domain. He hosted lavish feasts, mediated disputes, and shrewdly managed the flow of commerce that connected the isolated plains to the burgeoning markets of the East. His legend grew not from superhuman feats, but from his remarkable capacity for organization, his unwavering resolve, and his unique ability to command respect from both rough-hewn frontiersmen and proud tribal leaders.

Yet, like all legends, Culbertson’s story is tinged with the inevitable arc of change and decline. The fur trade, once the engine of western expansion, began to wane. The fashion for beaver hats in Europe gave way to silk, and the relentless hunting of buffalo for their robes started to decimate the vast herds. The arrival of steamboats, the encroachment of settlers, and the relentless march of "progress" heralded the end of the untamed frontier Culbertson had known. The "Kingdom of the Upper Missouri" was eventually sold, and the era of the independent fur trader faded into history.

Culbertson, ever the adaptable frontiersman, transitioned with the times. He continued to serve as an invaluable interpreter and negotiator for the U.S. government, playing a crucial role in pivotal treaty councils, including the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. Here, his deep understanding of Native American perspectives and his ability to articulate government positions in culturally appropriate ways were indispensable, helping to shape the boundaries and relations that would define the West for decades to come, albeit often imperfectly. He was a bridge-builder in a time of increasing division, striving to maintain peace even as the forces of expansion made conflict almost inevitable.

In his later years, Culbertson experienced financial setbacks and personal tragedies, a common fate for many who had prospered in the volatile frontier economy. He invested in ventures that failed, and the vast wealth he had accumulated through years of hard work eventually dwindled. But even in decline, his influence persisted. He had seen the West transformed from an immense wilderness to a landscape increasingly carved up by settlers and railroads. He had witnessed the shift from Native American sovereignty to federal control, and he had been an active participant in that profound, often painful, metamorphosis.

Alexander Culbertson’s legend is not one of a mythic hero battling fantastical beasts, but of a real man grappling with the immense forces of history. His story challenges the simplistic narratives of good versus evil often found in American folklore. He was a capitalist, driven by profit, yet he operated with a pragmatism and respect that was rare among his peers. He facilitated the expansion of American power, yet he also advocated for fair treatment of Native Americans. He embodied the contradictions and complexities of the American frontier – a place of immense opportunity and equally immense exploitation, of cultural clash and unexpected cooperation.

His legacy is the tangible mark he left on the West: the relationships he fostered, the knowledge he acquired, and the sheer force of his personality that shaped a crucial era. He reminds us that the true legends of America are often found not in the embellished tales of superhuman strength, but in the gritty, often ambiguous, lives of individuals who stood at the crossroads of history. Culbertson, the fur trader, diplomat, and intercultural navigator, is an unsung architect of the American West, a legend whose life, more than any tall tale, illuminates the true spirit, challenges, and enduring legacy of the nation’s formative years. His legend speaks to the power of human connection, the necessity of understanding, and the complex, often messy, reality of building a nation.