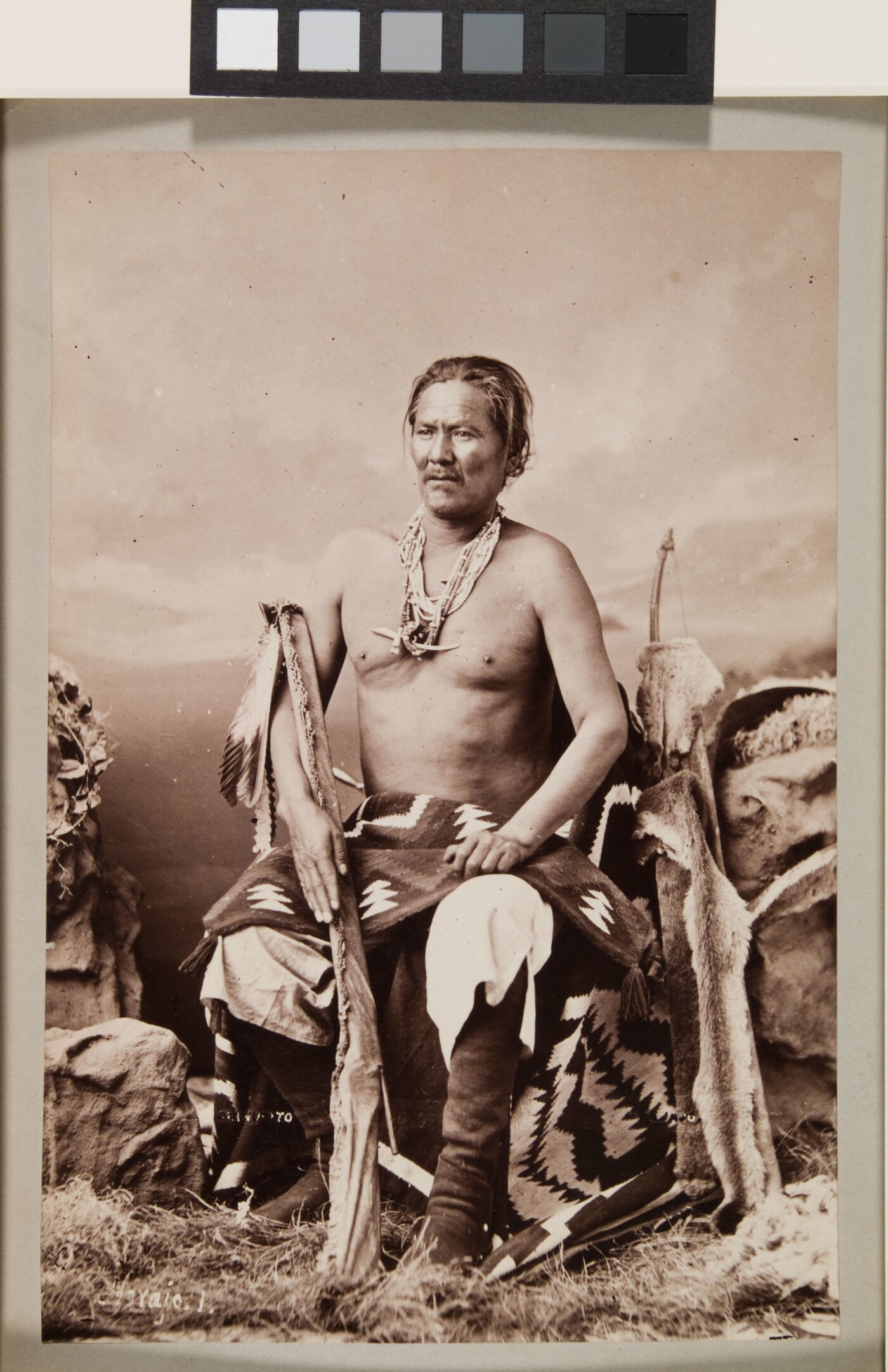

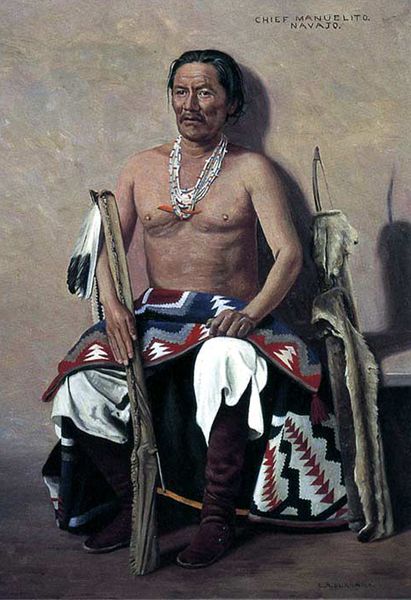

The Enduring Echoes of Resistance: Manuelito, Navajo War Chief, and the Legends of America

America’s tapestry of legends is often woven with threads of pioneering spirit, westward expansion, and heroic individualism. Yet, beneath the familiar narratives of cowboys and frontiersmen lies a deeper, more complex layer of stories – tales of resilience, profound injustice, and the unwavering spirit of indigenous peoples defending their ancestral lands. Among these, the saga of Manuelito, the formidable Navajo war chief (Hastiin Chʼil Haajiní), stands as a stark, powerful counter-narrative, challenging simplistic notions of American heroism and demanding recognition for the enduring strength of the Diné. His life, a testament to unyielding defiance and a pragmatic vision for survival, is not just a Navajo legend, but an essential chapter in the broader, often uncomfortably honest, legends of America.

Born around 1818 near Bear’s Ears in present-day Utah, Manuelito emerged during a period of escalating conflict between the Navajo people and encroaching American settlers and the U.S. military. The Diné, a proud and independent nation, had for centuries thrived in the vast, rugged landscapes of the American Southwest, their culture deeply intertwined with the land they called Dinétah. Manuelito, whose name translates to "Little Manuel" from Spanish, quickly distinguished himself not only as a skilled warrior and tactician but also as a charismatic leader with a profound understanding of his people’s traditions and an acute awareness of the existential threats they faced.

The mid-19th century brought the full force of American expansionism to the Southwest. Following the Mexican-American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the United States inherited vast territories, including Dinétah. This acquisition ushered in an era of escalating tensions, marked by broken treaties, retaliatory raids, and a fundamental clash of worldviews. For the U.S. government, the "Indian Problem" in the Southwest was an impediment to progress and settlement; for the Navajo, it was an invasion of their homeland and an assault on their very way of life.

Manuelito understood the gravity of the situation. Unlike some who advocated for immediate peace at any cost, he recognized that true peace could only be achieved if the Navajo’s sovereignty and land rights were respected. He became a leading voice of resistance, advocating for armed struggle against the encroaching forces. His military acumen was legendary, characterized by swift, strategic raids that confounded U.S. troops and Mexican militias alike. He was known for his ability to rally his people, inspiring them with his courage and his unwavering commitment to their freedom.

The decisive turning point in this conflict came during the American Civil War. With federal troops initially diverted to the Eastern Front, the defense of the Southwest fell to volunteer units, most notably the New Mexico Volunteers led by Colonel Christopher "Kit" Carson. Carson, a legendary frontiersman often romanticized in American lore, was tasked with pacifying the Navajo. His campaign, however, was not one of conventional warfare. It was a brutal, scorched-earth strategy aimed at destroying the Navajo’s economic base – their crops, livestock, and homes – to force their surrender.

From 1863 to 1864, Carson’s forces systematically laid waste to Dinétah. They burned cornfields, slaughtered sheep, destroyed hogans (traditional Navajo homes), and poisoned water sources. The objective was clear: make the Navajo’s homeland uninhabitable, leaving them with no choice but to surrender or starve. Manuelito, leading a faction of several thousand Diné, continued to resist fiercely, retreating into the most remote canyons and mesas. He famously declared, "My people, I have done all I can for you. I have fought the white man, I have made raids, I have tried to make peace. But it is useless. The white man is too strong."

Yet, even in the face of overwhelming odds, Manuelito refused to yield until his people’s survival depended on it. As winter approached, and starvation became a grim reality for his dwindling followers, Manuelito faced the agonizing decision. He saw his people dying from hunger and exposure, their spirit slowly breaking under the relentless pressure. In September 1866, after two years of relentless pursuit and a profound act of self-sacrifice, Manuelito, along with his remaining followers, surrendered to U.S. forces at Fort Wingate.

His surrender marked the tragic end of the Navajo War and the beginning of one of the darkest chapters in Navajo history: the Long Walk (Hwéeldi). Thousands of Navajo men, women, and children were forcibly marched hundreds of miles from their ancestral lands to Bosque Redondo, a desolate reservation near Fort Sumner in eastern New Mexico. It was a journey of immense suffering, akin to the Cherokee’s Trail of Tears, where countless lives were lost to starvation, disease, and exhaustion. The conditions at Bosque Redondo were horrific. The land was barren, water was scarce and brackish, and the U.S. government failed to provide adequate food, clothing, or shelter. The Navajo, a people accustomed to vast spaces and self-sufficiency, were confined, their spirit crushed by dependency and despair.

Manuelito, now a prisoner, continued to demonstrate his leadership. Even in captivity, he remained a voice for his people, advocating for better conditions and relentlessly pressing for their return home. He understood that the experiment at Bosque Redondo was a catastrophic failure, detrimental to both the Navajo and the U.S. government. His quiet dignity and persistent lobbying, alongside other Navajo leaders like Barboncito and Armijo, played a crucial role in convincing U.S. officials that the Bosque Redondo project was unsustainable.

In 1868, after four years of immense suffering, the U.S. government finally relented. A treaty was negotiated, allowing the Navajo to return to a portion of their ancestral lands. This historic event, known as the Treaty of 1868, established the Navajo Nation as a sovereign entity within the United States. Manuelito was a key signatory and instrumental in shaping the terms of the agreement, demonstrating a remarkable transition from war chief to statesman. His counsel was vital in securing a return to their homeland, a rare achievement for a defeated indigenous nation at that time.

The return journey, while a joyous homecoming, was also fraught with challenges. The Navajo had to rebuild their lives from scratch, their herds decimated, their fields barren. Manuelito, however, did not retreat into the shadows. He continued to serve his people as a headman, working tirelessly for their economic recovery and cultural preservation. He understood that survival in the new world required adaptation. He encouraged education, but on Navajo terms, advocating for schools that would teach their children the skills needed to navigate the dominant society while still honoring their traditions. He famously advised, "Take good care of your sheep and goats and horses, and then your families. Be honest, and live in peace. If you do this, you will grow to be a great nation."

Manuelito’s legacy is multifaceted and profound. For the Navajo people, he remains an iconic figure, a symbol of their enduring resilience, their unbreakable connection to their land, and their steadfast determination to preserve their culture in the face of immense pressure. His life story is a narrative of profound courage – not just the courage of a warrior on the battlefield, but the deeper courage to make agonizing choices for the survival of his people, and the wisdom to transition from armed resistance to diplomatic advocacy.

In the broader context of American legends, Manuelito’s story serves as a vital corrective. It challenges the romanticized view of westward expansion as an unblemished march of progress, revealing instead the often brutal realities of conquest and dispossession. His legend forces Americans to confront the difficult truths of their nation’s history, acknowledging the immense sacrifices made by indigenous peoples and the profound injustices they endured. It underscores that true American heroism is not solely found in the tales of victors, but also in the unwavering spirit of those who resisted, suffered, and ultimately survived.

Manuelito passed away in 1893, but his spirit lives on. His name is etched into the landscape of the Navajo Nation, invoked in stories, songs, and ceremonies. His struggle for sovereignty and self-determination continues to resonate in contemporary debates about indigenous rights, land stewardship, and cultural preservation. The "Legends of America" are incomplete without the powerful, poignant, and ultimately triumphant narrative of Manuelito – a war chief who, through his defiance and his wisdom, ensured that the Diné would not only survive but thrive, continuing to enrich the diverse tapestry of American identity. His is a legend not of conquest, but of endurance, a testament to the human spirit’s capacity to overcome, to adapt, and to always, always remember where it comes from.