The Bloody Mirror: Hannah Duston’s Revenge and the Unsettling Fabric of American Legend

The tapestry of American legends is woven with threads of heroism, endurance, and often, an unsettling brutality. Among these narratives, few resonate with the chilling power and moral complexity of Hannah Duston’s revenge. Her story, etched into the late 17th century, is not merely a tale of survival against impossible odds, but a stark, bloody mirror reflecting the raw savagery of the American frontier, challenging our definitions of courage, justice, and the birth of a nation. It is a legend that refuses to be neatly categorized, a testament to the primal forces that shaped a nascent America, and a potent reminder that history’s heroes are often forged in the crucible of unspeakable violence.

On March 15, 1697, the quiet frontier settlement of Haverhill, Massachusetts, was shattered by the horrors of King William’s War. This was a brutal conflict, often overshadowed by later wars, but one that saw French and Wabanaki Confederacy forces (primarily Abenaki) launch devastating raids against English settlements. These were not pitched battles between armies, but sudden, violent incursions designed to instill terror, capture prisoners, and reclaim ancestral lands encroached upon by the ever-expanding colonial tide.

Hannah Duston, a 39-year-old mother of eight, had just given birth to her ninth child, Martha, a mere week earlier. Her husband, Thomas Duston, was working in a field when the war party descended. With incredible presence of mind and courage, Thomas managed to shepherd seven of their children to safety, making them run ahead while he fought off the attackers with his musket. "He placed himself in the rear of his children," wrote the prominent Puritan minister Cotton Mather, a contemporary chronicler of the events, "and there stood facing about and firing upon the Indians, and so retreating, from tree to tree, that he got safe with these seven of his children into a garrison."

But Hannah, weakened by childbirth, could not flee. Along with her newborn infant and her nurse, Mary Neff, she was captured. The horrors began almost immediately. As the war party retreated into the wilderness, the cries of the infant Martha became an unbearable nuisance. One of the Abenaki warriors, with cold pragmatism, seized the baby and brutally bashed her head against an apple tree, killing her instantly. This act, recounted in Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana, was not merely a tragic detail; it was the spark that ignited a furnace of vengeance in Hannah Duston’s heart.

The arduous journey north into the wilderness was a gauntlet of physical and psychological torment. Hannah, Mary Neff, and other captives were forced to march through snow and frozen terrain, their grief and terror compounded by exhaustion and hunger. For Hannah, the image of her murdered infant would have burned brightest, transforming her into something beyond a mere victim. She was no longer just a mother mourning; she was a woman incubating a terrible, single-minded purpose.

Their captors, a band of twelve Abenaki, including two adult men, three women, and seven children, were heading for an established village where they intended to sell or adopt the captives. During their journey, they stopped at an island at the confluence of the Merrimack and Contoocook Rivers, near what is now Boscawen, New Hampshire. It was here that Hannah Duston’s plan began to coalesce.

Among the captives was a 14-year-old English boy named Samuel Lennard, who had been captured over a year earlier and was essentially integrated into the Abenaki family. He understood their language and customs. According to Mather’s account, one of the Abenaki men, perhaps sensing their despair or simply engaging in a perverse form of "education," spoke to the captives about their customs. He reportedly showed them how to scalp a person, explaining the technique and the purpose – to collect bounties offered by the French for English scalps. This chilling lesson, intended perhaps to illustrate their vulnerability or the cycle of frontier violence, inadvertently provided Hannah Duston with the very tools for her revenge.

Hannah, with the unwavering support of Mary Neff and the crucial participation of Samuel Lennard, began to formulate her desperate scheme. She would have to act swiftly, decisively, and with extreme violence. The risk was immense; failure meant certain death, probably agonizing. But the memory of her baby, the trauma of her capture, and the prospect of a brutal future spurred her on.

In the dead of night, while their captors slept soundly, Hannah, Mary, and Samuel rose. They armed themselves with hatchets, the very tools used by their captors. What followed was an act of cold-blooded retribution that has shocked and fascinated generations. They moved through the sleeping encampment, striking down ten of the twelve Abenaki. They spared one woman and a child, either out of some flicker of mercy or perhaps because they were too young to pose a threat. The victims included two adult men, two adult women, and six children – the very children who had been sleeping beside them.

After the brutal slayings, Hannah Duston, driven by a desire for undeniable proof of her actions and perhaps by the knowledge of bounties offered by the colonial government for Native American scalps, proceeded to scalp all ten of the dead. This act, horrifying to modern sensibilities, was a grim reality of frontier warfare for both sides. Scalps were often taken as trophies, as proof of kills, and as currency in the brutal economy of colonial conflict. It was a practice tragically adopted by both Europeans and Native Americans in the escalating cycle of violence.

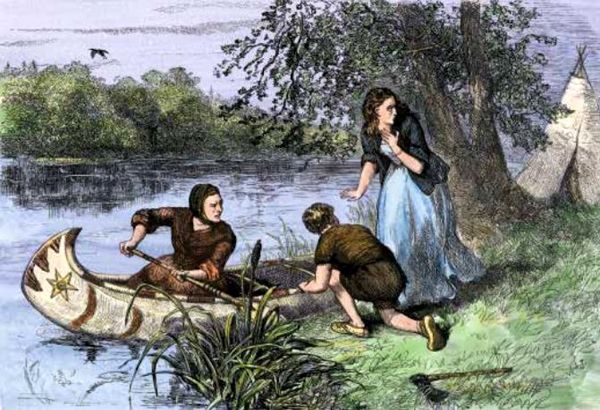

With their gruesome trophies in hand, the three survivors then stole a canoe and paddled down the Merrimack River, navigating treacherous currents and hidden dangers, until they reached the safety of Haverhill. The sight of Hannah Duston, Mary Neff, and Samuel Lennard returning, alive and bearing ten bloody scalps, must have been both a cause for celebration and a source of profound horror for the beleaguered colonists.

Their return was not met with condemnation, but with awe and admiration. Cotton Mather, in his influential account, presented Hannah Duston as a divinely inspired heroine, an instrument of God’s vengeance against "barbarous Infidels." He praised her "heroic action" and saw her as a testament to the strength and piety of the Puritan spirit. The Massachusetts General Court rewarded the trio with a bounty of fifty pounds – a substantial sum at the time – for their "brave exploit." Later, the governor of Maryland, upon hearing the tale, sent an additional twenty-five pounds.

Hannah Duston became an instant celebrity, a symbol of frontier resilience and righteous vengeance. Her story was told and retold, shaping the emerging American narrative of the brave pioneer triumphing over the "savage" wilderness. In the 19th century, as America expanded westward and solidified its national identity, Duston’s legend was further romanticized. She was immortalized in poetry, prose, and public monuments. Statues were erected in her honor, notably in Boscawen, New Hampshire (1874), and Haverhill, Massachusetts (1879), depicting her with a hatchet raised, a grim avenger. These monuments cemented her place as one of America’s first female heroes, a fierce mother protecting her progeny and striking back at her tormentors.

However, as historical understanding evolved, so too did the perception of Hannah Duston’s actions. The 20th and 21st centuries brought a more nuanced, and often critical, lens to her story. Historians began to question the celebratory narrative, grappling with the moral implications of killing and scalping sleeping children. Was it heroism, or was it an act of horrific murder, albeit under extreme duress?

From a modern perspective, the act of scalping children is undeniably gruesome and morally reprehensible. Yet, to understand Hannah Duston, one must attempt to inhabit the brutal world she inhabited. The frontier was a place where survival often demanded unspeakable acts. The line between victim and perpetrator blurred in a cycle of violence fueled by fear, revenge, and land disputes. The Abenaki, too, were fighting for their survival, retaliating against colonial expansion, disease, and broken treaties. Their raid on Haverhill was part of this larger, tragic conflict.

The legend of Hannah Duston thus becomes a potent, if uncomfortable, case study in the selective memory and myth-making inherent in nation-building. It forces us to confront the darker elements of our origins, the moments when the "heroes" of one narrative are the "villains" of another. For Native American communities, her statues and the celebratory accounts are painful reminders of colonial violence and the dehumanization of their ancestors.

The Hannah Duston legend serves as a crucial reminder that the American frontier was not a simple landscape of good versus evil. It was a crucible where human beings, under immense pressure, committed acts of both extraordinary courage and unfathomable cruelty. Her story is not just about a woman’s revenge; it is about the brutal birth pangs of a nation, the complex interplay of trauma and vengeance, and the enduring challenge of reconciling our romanticized past with its grim realities.

Today, Hannah Duston remains a figure of intense debate. She is a powerful symbol of resilience, a woman who refused to be a passive victim. Yet, she is also a stark reminder of the ethical compromises made in the name of survival and the cyclical nature of violence. Her legend, far from being a simple tale of heroism, forces us to look into a bloody mirror and ask difficult questions about the foundations of American identity, the nature of revenge, and the uncomfortable truths that lie beneath the surface of our most cherished myths. It is a story that, despite its horrific details, continues to haunt us, demanding that we acknowledge the full, complex, and often unsettling fabric of our history.