Echoes in the Granite: Connecticut’s Forgotten Witch Hunts

In the annals of American history, the year 1692 looms large, a chilling timestamp marking the infamous Salem Witch Trials. Yet, long before the hysteria gripped Massachusetts Bay Colony, a darker, quieter terror had already taken root in the verdant, granite-strewn lands of Connecticut. Here, in the nascent Puritan settlements, fear, superstition, and social anxieties coalesced into a series of witch hunts that, though less widely known, were arguably more brutal in their initial fervor and set a grim precedent for the tragedies that would follow. This is the story of Connecticut’s forgotten witch hunts, a stark reminder of the fragile line between faith and fanaticism, and the enduring human capacity for both fear and resilience.

The early 17th century in New England was a time of immense hardship and unwavering faith. Settlers grappled with unforgiving wilderness, disease, crop failures, and the ever-present threat of Native American conflict. For the devout Puritans, these struggles were often interpreted through a deeply spiritual lens: God’s will, or the Devil’s insidious work. The "invisible world" of spirits, angels, and demons was not a metaphor but a tangible reality, and the Devil was believed to actively recruit human agents – witches – to sow discord and misery among God’s chosen people.

It was against this backdrop of fervent piety and existential dread that the first accusation of witchcraft in the American colonies emerged, not in Salem, but in Windsor, Connecticut. In 1647, Alse Young, an older woman whose life remains largely shrouded in mystery, was accused, tried, and subsequently hanged for witchcraft. Her execution on May 26, 1647, marked a somber first for a continent still finding its footing. The records are sparse, offering little detail beyond her name and the date of her death, a testament to how quickly such events were accepted and then often deliberately obscured. Yet, her fate set a terrifying precedent, opening the door for further accusations and cementing the belief that witches walked among them.

The years following Alse Young’s execution saw a disturbing acceleration of accusations across Connecticut. Unlike the concentrated outbreak in Salem, Connecticut’s witch hunts were more diffuse, often occurring in distinct clusters within various towns. These early cases were characterized by a chilling lack of formal process and a swift journey from accusation to gallows.

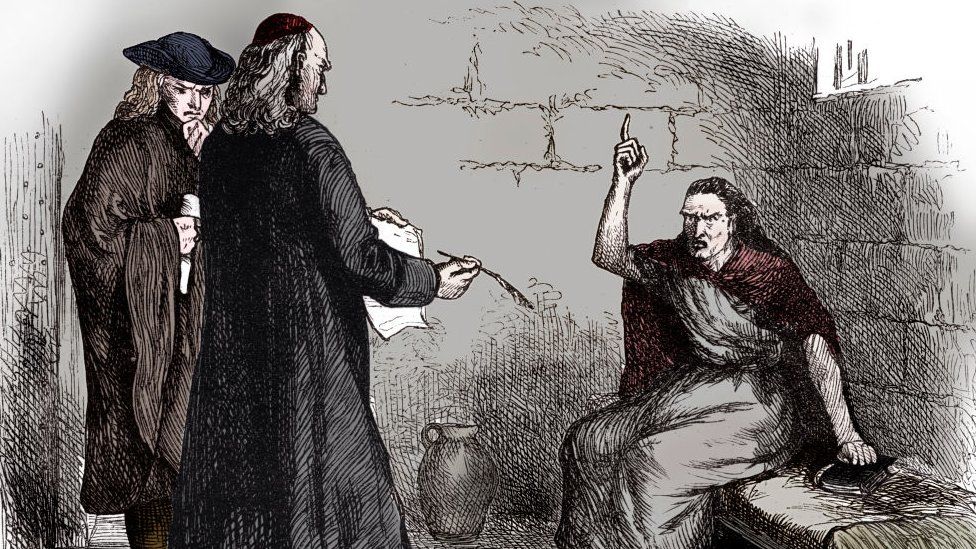

One of the most revealing early cases involved Mary Johnson of Wethersfield in 1648. Accused of being a witch, Johnson confessed under duress, providing a detailed account that mirrored the nascent European witch lore. She claimed to have consorted with the Devil, describing flying, sexual encounters with infernal figures, and participating in secret covens. Her confession, though almost certainly coerced, was deemed sufficient proof and she was hanged. Her story, preserved in the writings of colonial figures like Increase Mather, offered a terrifying blueprint for later accusations, solidifying the idea that witches were not merely a threat but a present, tangible evil within the community.

The profile of the accused in Connecticut often mirrored patterns seen elsewhere: women, often older, widowed, or unmarried, who were perceived as somehow outside the patriarchal social norms. Those with sharp tongues, independent minds, or who practiced traditional healing arts were particularly vulnerable. If a neighbor’s cow fell ill, a child suffered a mysterious ailment, or a crop failed, the finger of suspicion often pointed to the marginalized woman living on the edge of the community, her misfortune or distinctiveness transformed into evidence of maleficium – the doing of evil by supernatural means.

The legal framework for these trials was rudimentary and heavily biased against the accused. "Spectral evidence," where accusers claimed to see the spirit of the accused tormenting them, was often accepted. "Touch tests," where an accused witch was made to touch a tormented victim, and if the torment ceased, it was proof of guilt, were also employed. The presence of a "witch’s mark" – a mole, birthmark, or any unusual blemish – could be interpreted as a sign of the Devil’s pact. Confession, often extracted through sleep deprivation, intimidation, or even torture, was considered the most damning evidence of all.

Wethersfield, Windsor, and Fairfield emerged as particular hotspots. In Wethersfield, several individuals faced accusations, including Goodwife Bassett, who was executed in 1651. In Windsor, the elderly Lydia Gilbert was hanged in 1654, accused of causing a man’s death after a shooting accident. These were not isolated incidents but part of a creeping terror that saw families torn apart and communities consumed by paranoia.

However, Connecticut’s witch hunt narrative also holds a unique and crucial distinction: it contained the seeds of its own demise well before the Salem frenzy. A key figure in this shift was Governor John Winthrop Jr. A man of science and medicine, Winthrop was deeply skeptical of spectral evidence and the more extreme forms of accusation. As a magistrate, he often intervened in trials, advocating for leniency, demanding more concrete evidence, and urging caution. His influence, combined with a growing unease among some ministers and magistrates about the increasingly flimsy basis for convictions, began to slow the tide.

A pivotal moment occurred in Fairfield in 1692, the very year Salem erupted. Mercy Disborough, a local woman, was accused of witchcraft. Her trial became a legal battleground, with Winthrop and other skeptics pushing back against the use of spectral evidence. Despite initial conviction by a local jury, Disborough was eventually acquitted by the colonial General Court of Assistants, a decision that signaled a critical turning point. This acquittal, based on a rejection of the more fantastical claims, effectively put an end to capital witchcraft convictions in Connecticut, almost a year before the Salem trials peaked and began their own agonizing collapse.

By the time the Salem hysteria reached its zenith, resulting in 20 executions, Connecticut had largely moved past its own period of intense witch hunting. The colony had executed at least 11 individuals for witchcraft, and many more had been accused, imprisoned, or had their lives irrevocably shattered. The experience of Connecticut, therefore, offers a more nuanced understanding of early American witch trials. It shows a society grappling with its fears, but also one capable of introspection and, eventually, a reasoned retreat from mass hysteria, albeit at a terrible cost.

The legacy of Connecticut’s witch hunts remained largely unacknowledged for centuries. Unlike Salem, which became a cultural touchstone, the names and stories of Connecticut’s accused were largely forgotten, buried under layers of historical silence and local shame. Only in recent decades have efforts been made to exhume these forgotten narratives, to honor the victims, and to understand the profound lessons embedded in their suffering.

Organizations like the Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project and local historical societies have worked tirelessly to bring these stories to light, advocating for official exonerations and establishing memorials. These efforts are not merely about correcting historical records; they are about confronting a dark chapter and understanding how fear and intolerance can warp justice.

In a world still grappling with misinformation, "cancel culture," and the rapid spread of unsubstantiated accusations, the echoes from Connecticut’s granite hills resonate with chilling relevance. The witch hunts of the 17th century serve as a potent reminder of the dangers of unchecked accusations, the fragility of due process, and the profound human cost when societies surrender to fear and prejudice. The names of Alse Young, Mary Johnson, Lydia Gilbert, and others, once whispered in terror, now stand as solemn sentinels, urging us to remember, to learn, and to forever remain vigilant against the forces that seek to condemn without proof, and to destroy lives in the name of an imagined evil. Their story, though long overshadowed, is an indispensable chapter in the ongoing narrative of justice and human rights in America.