The Enduring Flame: A Legacy of Treaties and Resilience for the Potawatomi Nation

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

In the verdant embrace of the Great Lakes region, where the whispers of ancient forests mingle with the lapping of freshwater shores, once thrived the Bodéwadmi, the Potawatomi. Known as the "Keepers of the Fire" – the central council fire of the Anishinaabeg Confederacy (which included the Ojibwe and Odawa) – their domain stretched across what is now Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Ohio, and parts of Ontario. Their history, rich with cultural depth and deep connection to the land, is inextricably linked to a complex web of treaties – agreements that, over centuries, transformed their lives, diminished their lands, yet paradoxically, also laid the groundwork for their enduring sovereignty.

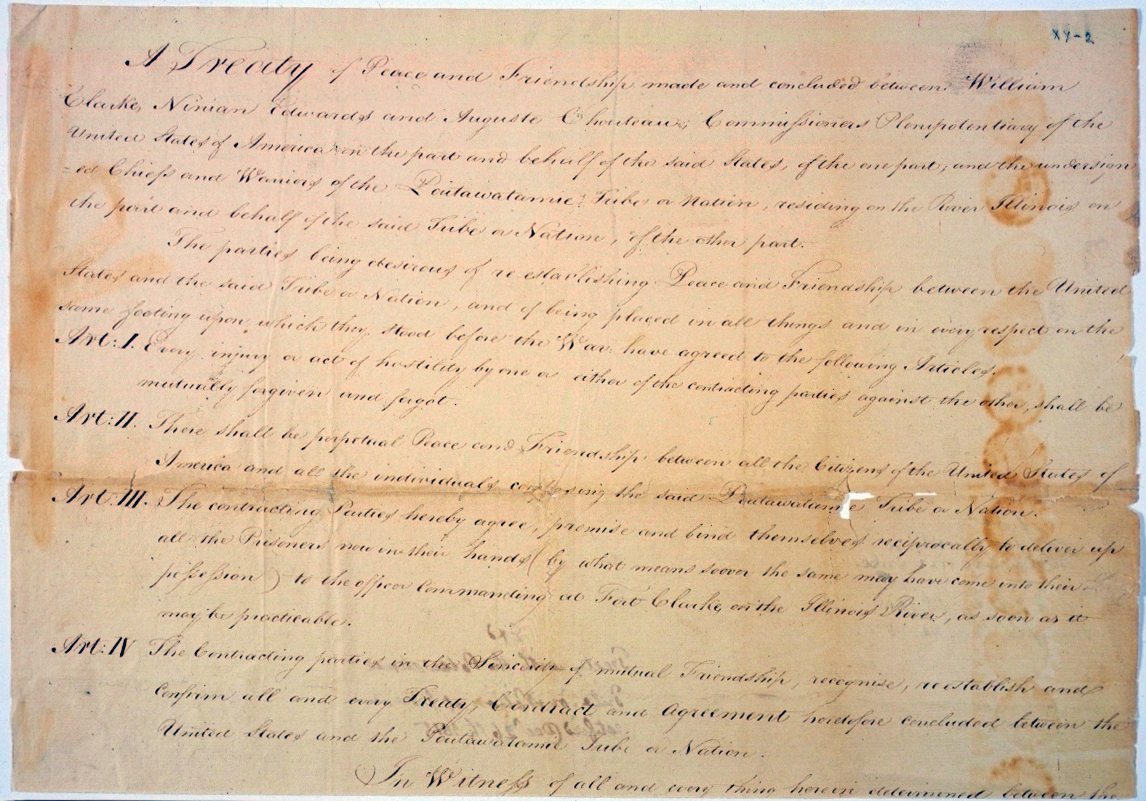

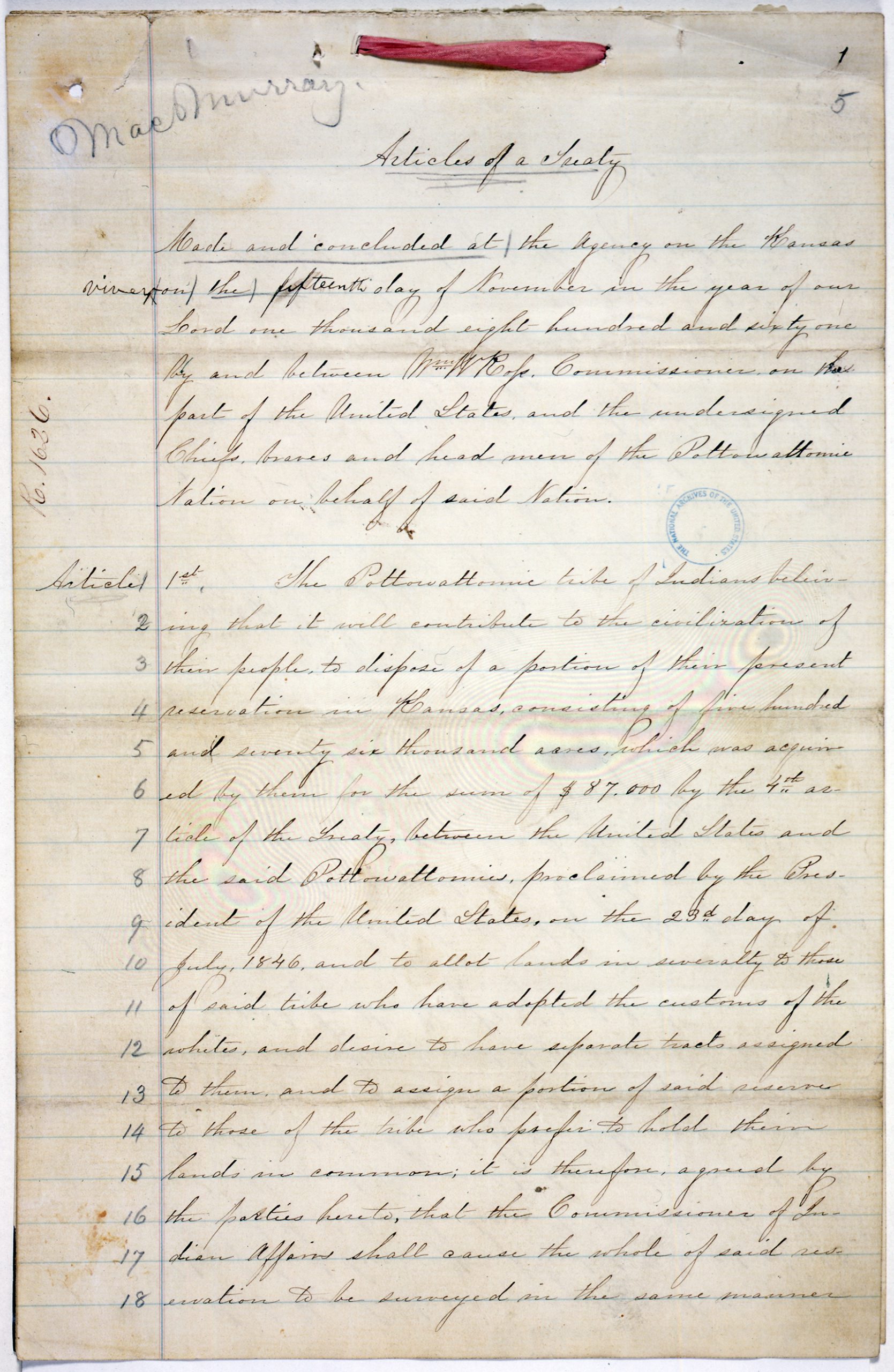

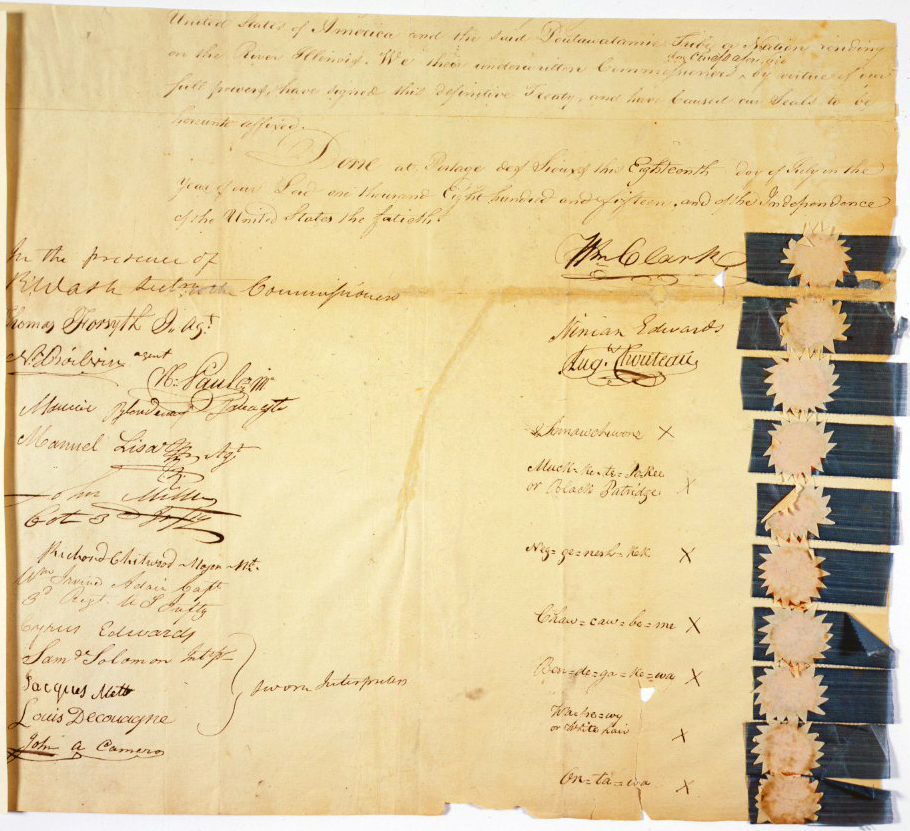

These treaties, numbering over 100 with the United States alone, are not mere historical documents. They are living instruments, scars of past injustices, and foundations for present-day rights. They tell a story of strategic alliances, economic shifts, overwhelming pressure, forced removal, and ultimately, an unyielding spirit of self-determination that defines the Potawatomi Nation today.

From Alliance to Cession: The Early American Encounters

The Potawatomi’s interactions with European powers began in the 17th century with the French, primarily through the fur trade. These early relationships were often based on mutual respect and military alliances, particularly against rival Indigenous nations and later, the British. The French, unlike the British and later the Americans, were less interested in outright land ownership and more in trade and strategic partnerships.

The shift in power following the French and Indian War (1754-1763) brought the British into prominence, and with them, a more aggressive stance on land. Potawatomi leaders, including the influential Chief Pontiac, were central figures in the resistance against British encroachment, highlighting an early, albeit ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to unite Indigenous nations against colonial expansion.

The true turning point came with the birth of the United States. The nascent American republic, fueled by the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and a burgeoning population, viewed the vast Indigenous lands as ripe for settlement. The Treaty of Fort Harmar in 1789, a follow-up to the Treaty of Fort McIntosh (1785), saw early, albeit limited, land cessions from various tribes, including the Potawatomi, to the United States. These were precursors to a flood of agreements.

Perhaps the most significant early treaty was the Treaty of Greenville (1795). Following the Northwest Indian War, where the Potawatomi fought alongside other tribes against American expansion, this treaty effectively ended major hostilities in the Ohio Valley. While it established a "treaty line" that theoretically protected some Indigenous lands, it also marked the beginning of substantial land cessions. For the Potawatomi, it was a bitter pill, surrendering large portions of what is now Ohio and southeastern Indiana. It was a forced peace, born of military defeat, rather than genuine negotiation among equals.

The Accelerating Pace of Dispossession: The 19th Century Onslaught

The early 19th century saw an exponential increase in treaty negotiations, driven by American land hunger and the insatiable demand for agricultural expansion. The Potawatomi, along with other Great Lakes tribes, found themselves caught in a relentless vise. Treaties were often negotiated under duress, with promises of annuities (annual payments), goods, and services that frequently went unfulfilled or were siphoned off by corrupt agents. "Whiskey treaties," where alcohol was used to impair judgment and coerce signatures, were not uncommon.

A prime example of this escalating pressure was the Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809), where William Henry Harrison, then governor of Indiana Territory, secured over 3 million acres of land from various tribes, including the Potawatomi, for a paltry sum. This land grab further fueled resentment and contributed to the rise of Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, who sought to unite tribes against American encroachment. Many Potawatomi warriors joined Tecumseh’s Confederacy, fighting valiantly at the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811) and later in the War of 1812, often siding with the British in a desperate bid to protect their homelands. Their efforts, however, were ultimately unsuccessful.

The most devastating period of treaty-making and land loss for the Potawatomi came in the 1830s, fueled by President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830. This federal policy aimed to forcibly relocate all Native American tribes west of the Mississippi River. The Potawatomi, despite their long history in the Great Lakes, were no exception.

The Treaty of Chicago (1833) stands as a monumental example of this era. Signed by a relatively small group of Potawatomi leaders, many under duress or without full authority, it ceded over 5 million acres of prime land, including the site of modern-day Chicago, for what amounted to pennies an acre. The treaty promised new lands in Kansas, but the process of removal was brutal and poorly managed.

The "Trail of Death": A Forced Exodus

The most tragic consequence of these removal treaties was the Potawatomi Trail of Death in 1838. Following the Treaty of Yellow River (1836), which mandated the removal of the Potawatomi in Indiana, approximately 859 Potawatomi people, led by their revered Catholic spiritual leader, Chief Menominee, were forcibly marched 660 miles from Twin Lakes, Indiana, to lands in Kansas.

"We have been told that our Father, the President, wished us to go to the other side of the Mississippi, and we have been promised money and the goods we need for our journey," Chief Menominee had said, "but we have not seen them. We want to live here where we were born, where our fathers and grandfathers died, where our children are buried. We do not want to go to a strange country."

Despite his impassioned pleas and the clear injustice, the march began in September, under the guard of armed militia. The conditions were horrific: lack of food, water, and sanitation, coupled with extreme heat and disease. Over 40 people, primarily children and the elderly, died during the two-month ordeal. This forced march serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of the U.S. government’s removal policies.

Fragmentation and Resilience: The Scattered Fires

The removal era did not result in a single, unified Potawatomi nation in the West. Instead, it led to fragmentation. Those who survived the Trail of Death settled primarily in Kansas, forming the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. Later, some of these were again moved to Indian Territory (Oklahoma), becoming the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

However, not all Potawatomi were removed. Some, through strategic alliances, legal maneuvering, or simply by hiding and resisting, managed to remain in their ancestral homelands. The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians in Michigan, for instance, were one of the few bands who managed to negotiate the right to remain due to their earlier conversion to Catholicism and a more settled agricultural lifestyle. Similarly, the Forest County Potawatomi Community and the Hannahville Indian Community in Wisconsin and Michigan, respectively, represent other groups who avoided forced removal, often by retreating into remote areas or negotiating specific terms.

This dispersal meant that the "Keepers of the Fire" now maintained several distinct fires across the continent, each with its own unique history of survival, adaptation, and a fierce determination to preserve their culture and sovereignty.

The Long Road to Reaffirmation and Self-Determination

The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought further challenges, including the Dawes Act (Allotment Act) of 1887, which sought to break up communal tribal lands into individual parcels, further eroding tribal sovereignty and leading to more land loss. The Potawatomi, like many tribes, faced relentless pressure to assimilate.

However, the mid-20th century marked a turning point. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 provided a framework for tribes to re-establish their governmental structures. Later, the Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 empowered tribes to take control of their own affairs, from education and healthcare to economic development.

Today, the various Potawatomi nations – including the Citizen Potawatomi Nation (Oklahoma), Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation (Kansas), Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians (Michigan/Indiana), Forest County Potawatomi Community (Wisconsin), Hannahville Indian Community (Michigan), Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Potawatomi Indians (Gun Lake Tribe) (Michigan), Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi (Michigan), and several bands in Canada – are vibrant, self-governing entities.

They have leveraged their inherent sovereignty, often rooted in the very treaties that once dispossessed them, to build thriving economies through diversified businesses, including gaming, manufacturing, and tourism. They are actively engaged in cultural revitalization, language preservation, and environmental stewardship, reclaiming their heritage and ensuring its continuity for future generations.

The treaties, once instruments of profound loss, are now often cited in legal battles to affirm hunting, fishing, and water rights, or to reclaim ancestral lands. They serve as a constant reminder of the United States’ historical obligations and the inherent sovereignty of Native nations.

The Enduring Flame

The history of the Potawatomi Nation’s treaties is a powerful narrative of resilience against overwhelming odds. It is a story of a people who, despite facing systematic dispossession and cultural assault, refused to be extinguished. The "Keepers of the Fire" have not only kept their ancestral flame alive, but they have also rekindled it into a beacon of self-determination, reminding us all that true sovereignty is not granted; it is inherent, enduring, and eternally guarded by the spirit of a people deeply connected to their past and fiercely committed to their future. The legacy of these treaties, both painful and empowering, continues to shape the identity and trajectory of the Potawatomi Nation, a testament to their unwavering strength and spirit.