The Shadow of Metacomet: King Philip’s War and America’s Unsettled Legend

In the annals of American history, certain conflicts resonate with the weight of foundational myths, shaping the national consciousness long after the last shot is fired. Among these, none is perhaps more brutally illustrative of the continent’s origins than King Philip’s War, a cataclysmic struggle fought in the heart of New England between 1675 and 1678. Often overshadowed by later, more nationally celebrated wars, this desperate clash between English colonists and a confederation of Native American tribes led by the Wampanoag sachem Metacomet – known to the English as King Philip – remains a pivotal, yet profoundly unsettling, legend of America. It was a war of total devastation, a crucible that forged a nascent colonial identity while simultaneously decimating indigenous populations and forever altering the landscape of power and memory.

To understand King Philip’s War is to delve into a volatile frontier where two vastly different civilizations collided, each clinging to their own vision of the land and their place within it. For decades prior, a fragile peace had largely held, a legacy of the initial compact between Metacomet’s father, Massasoit, and the Plymouth colonists. This alliance, famously solidified at the first Thanksgiving, had allowed the English to establish a foothold. But as the Puritan settlements expanded, so too did the pressure on Native lands and sovereignty. English common law began to supersede tribal customs, livestock trampled Native cornfields, and Christian missionaries sought to convert the "heathen" natives, often relocating them to "praying towns" – a well-intentioned but culturally disruptive policy that further eroded traditional ways of life.

Metacomet, who became sachem in 1662, inherited a precarious position. He witnessed firsthand the relentless encroachment and the diminishing autonomy of his people. His attempts to negotiate and adapt, including selling land to the colonists, ultimately proved insufficient to stem the tide. He saw his people increasingly treated as subjects rather than sovereign partners. The growing mistrust was palpable, a powder keg waiting for a spark.

That spark came in January 1675, with the murder of John Sassamon, a "praying Indian" who had served as an interpreter and advisor to both Metacomet and the English. Sassamon had reportedly warned the Plymouth authorities of an impending Native uprising, an act viewed as treason by Metacomet and his followers. When three Wampanoag men were tried by an English jury (which included "praying Indians") and executed for Sassamon’s murder, Metacomet saw it as an intolerable usurpation of his authority and a profound injustice. This act of colonial jurisprudence, perceived as a violation of sovereignty, pushed Metacomet to a fateful decision: to resist by force.

What followed was a war of unparalleled ferocity and devastation for its time. Metacomet, a brilliant strategist and charismatic leader, forged a confederation of tribes including the Wampanoag, Nipmuc, Pocumtuc, and Narragansett. His forces, intimately familiar with the terrain and employing effective guerrilla tactics, launched swift, devastating raids on colonial frontier towns. The war quickly spiraled into a conflict of scorched earth and utter brutality on both sides.

"The English had long enjoyed a comfortable sense of security," writes historian Jill Lepore in The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity, "but the war shattered this illusion, revealing the precariousness of their foothold in the New World." Indeed, the sheer scale of the conflict shocked the colonists. Within months, twelve out of ninety English towns were completely destroyed, and many more were damaged. Casualty rates were staggering: an estimated 10-15% of the colonial male population of military age was killed, a higher proportion than in any other American war. For comparison, this would be akin to millions of American deaths in a modern conflict.

The Native forces, fighting for their very survival and ancestral lands, initially achieved significant successes. They ambushed colonial militias, burned settlements like Lancaster and Deerfield, and terrorized the frontier. Women and children were not spared; families were massacred or taken captive. The psychological impact on the colonists was immense, fueling a fear and hatred that would color Anglo-Native relations for centuries.

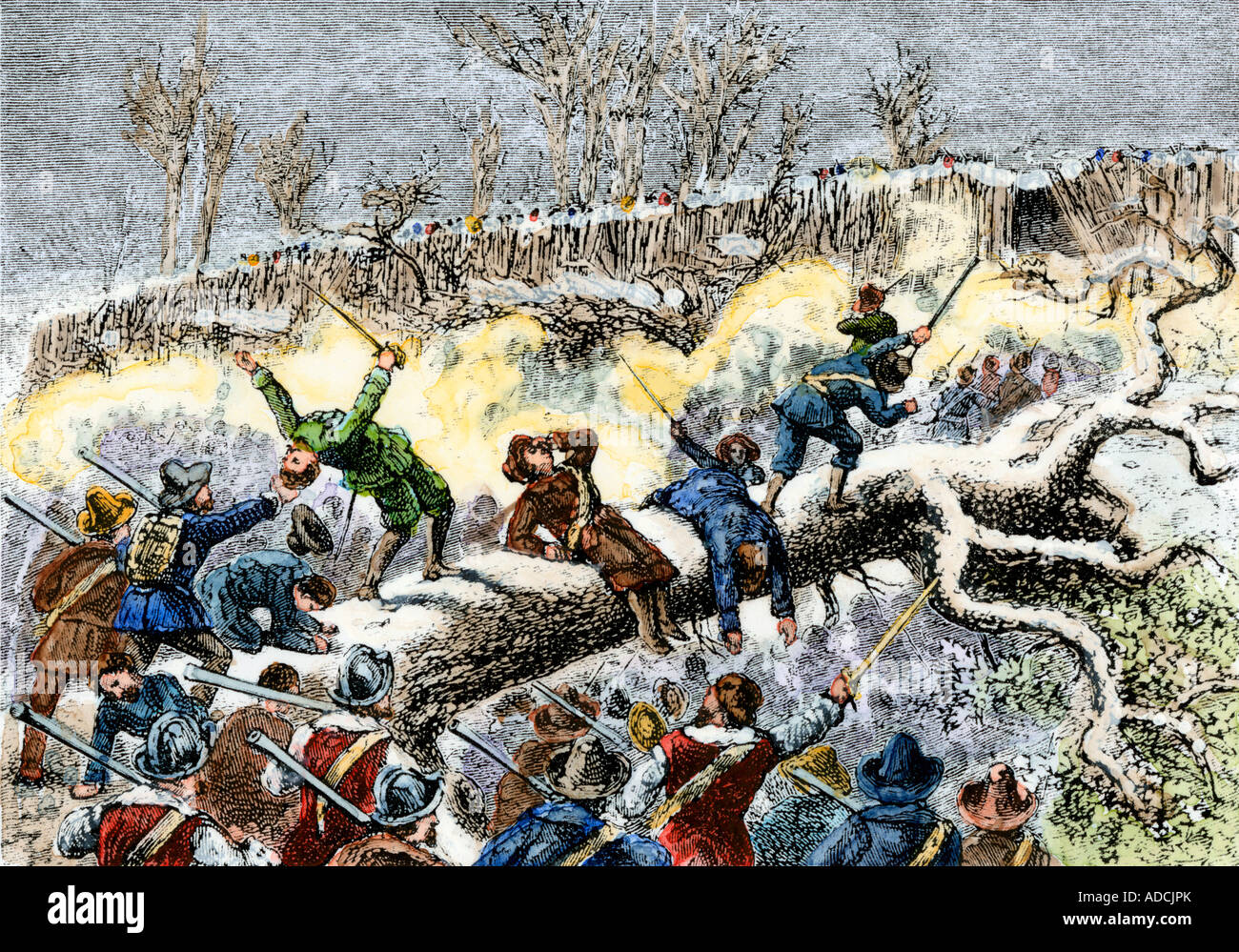

However, the tide began to turn. The colonists, though initially disorganized, eventually mobilized, forming inter-colonial militias. Their superior firepower, combined with a relentless scorched-earth policy, began to take its toll. A crucial turning point came in December 1675 with the "Great Swamp Fight." Despite the Narragansett tribe’s declared neutrality, the colonists, fearing they would join Metacomet, launched a surprise attack on their fortified winter village in present-day South Kingstown, Rhode Island. In a brutal, hours-long battle, hundreds of Narragansett warriors, women, and children were killed, and their village, along with vital winter provisions, was burned. This devastating blow crippled the Narragansett and broke the back of the Native resistance, effectively cutting off Metacomet’s primary source of potential allies and supplies.

The war then became a desperate struggle of attrition for Metacomet’s dwindling forces. Facing starvation, disease, and relentless pursuit, many Native warriors were forced to surrender or defect. The English also made use of "praying Indians" as scouts and guides, a controversial but effective strategy that pitted Native against Native, further fracturing indigenous unity. The colonists offered bounties for Native scalps, a practice that dehumanized the enemy and incentivized extreme violence.

By the summer of 1676, Metacomet was on the run, his confederation shattered, his family captured and sold into slavery in the West Indies. He returned to his ancestral home on Mount Hope in Rhode Island, a tragic figure witnessing the destruction of everything he had fought for. On August 12, 1676, he was tracked down by a colonial militia, led by Captain Benjamin Church, and killed by a "praying Indian" named John Alderman.

The indignities did not end with his death. Metacomet’s body was dismembered; his head was severed and sent to Plymouth, where it was impaled on a pike and displayed in the town square for over two decades, a grim trophy and a stark warning to any who dared defy colonial power. His hand, recognizable by a scar from a pistol burst, was sent to Boston. The war officially ended in 1678 with the Treaty of Casco, but its devastating effects lingered for generations.

The immediate aftermath of King Philip’s War was a colonial victory, but at an immense cost. The Native American population of southern New England was decimated; many were killed, captured, or forced to flee westward, their traditional way of life shattered beyond repair. Those who remained faced continued subjugation and dispossession. For the colonists, the victory cemented their dominance, but it also left deep scars. The war reinforced a narrative of righteous struggle against "savage" enemies, shaping a nascent American identity that often overlooked the complexities and injustices of the conflict.

The legend of King Philip’s War is multifaceted. For the English colonists, it became a story of survival, of divine providence guiding their expansion, and of the necessary subjugation of a dangerous wilderness. Philip himself was often demonized as a bloodthirsty tyrant, a symbol of indigenous resistance that needed to be crushed for the sake of "civilization." This narrative, steeped in the biases of the victors, dominated historical accounts for centuries.

However, for Native Americans, Metacomet became a tragic hero, a symbol of resistance against overwhelming odds, a fierce defender of his people’s land and culture. His struggle represents a profound loss, the beginning of a long period of dispossession and cultural suppression. Modern scholarship has increasingly sought to reclaim and recontextualize Metacomet’s story, recognizing him not as a savage, but as a strategic leader who fought with desperation and courage for his people’s very existence.

King Philip’s War, therefore, is more than just a historical event; it is a foundational American legend, albeit one steeped in blood and sorrow. It underscores the brutal realities of colonial expansion, the clash of irreconcilable worldviews, and the enduring legacy of violence that shaped the nation. The conflict set precedents for future Indian wars, solidified the racial divide between Europeans and Native Americans, and fundamentally altered the demographic and political landscape of New England.

Today, the battlefields and former villages of King Philip’s War are largely quiet, their stories often buried beneath layers of subsequent history. Yet, the shadow of Metacomet and the war he led continues to linger. It reminds us that America’s legends are not always triumphant tales of Manifest Destiny; they are also complex, often painful narratives of resistance, loss, and the enduring struggle to reconcile a past that is far from settled. Understanding King Philip’s War is crucial to comprehending the deep roots of identity, land, and conflict that continue to shape the American experience, making it a legend that, though uncomfortable, remains profoundly essential.