Echoes of Conflict: The Enduring Impact of the Black Hawk War on the Sauk Nation

The summer of 1832 was a crucible of conflict in the American Midwest, a violent climax to decades of encroaching American expansion. What began as a desperate attempt by a band of Sauk, Meskwaki (Fox), and Kickapoo people, led by the venerable warrior Black Hawk, to reclaim their ancestral lands, quickly devolved into a brutal and largely one-sided war. While often overshadowed in mainstream American history by grander narratives of Manifest Destiny, the Black Hawk War left an indelible scar on the Sauk Nation, profoundly shaping their identity, land base, political autonomy, and cultural survival for generations to come. Its echoes resonate even today, a stark reminder of the devastating human cost of westward expansion.

The Seeds of Dispossession: A Treaty of Contention

To understand the war’s impact, one must first grasp its origins. The Sauk and Meskwaki people had long inhabited the fertile lands around the confluence of the Mississippi and Rock Rivers, in what is now Illinois and Iowa. Their way of life was intrinsically linked to these lands – for hunting, farming, and the burial of their ancestors. However, the relentless westward march of American settlers, fueled by a hunger for land and a belief in their own civilizational superiority, put immense pressure on Native American territories.

The flashpoint was the Treaty of St. Louis in 1804. Signed by a handful of Sauk chiefs, allegedly without the full consent or understanding of the broader nation, this treaty ceded vast tracts of Sauk and Meskwaki land, including their primary village of Saukenuk, to the United States. While the U.S. government considered it a legitimate transaction, many Sauk, including Black Hawk, viewed it as fraudulent and illegitimate. Black Hawk himself later recounted in his autobiography, "I touched the goose quill to the treaty, not knowing that by that act I consented to give away my village." This fundamental disagreement over land ownership and the legitimacy of the treaty created a simmering resentment that would eventually boil over.

For decades, a precarious peace held. The Sauk continued to live in Saukenuk, but American settlers steadily encroached, establishing farms and towns. Tensions escalated, and the Sauk found themselves caught between two worlds: their traditional way of life and the relentless advance of American "progress."

Black Hawk’s Stand: A Desperate Return

By the spring of 1832, the situation for Black Hawk’s band, often referred to as the "British Band" due to their past alliance with the British against the Americans, became untenable. Facing starvation and constant harassment from settlers and the Illinois militia, Black Hawk, then in his mid-sixties, made a fateful decision. Defying the advice of his rival, Chief Keokuk, who advocated for peaceful accommodation, Black Hawk led approximately 1,000 Sauk, Meskwaki, and Kickapoo people – including many women, children, and elderly – back across the Mississippi River into Illinois. His intention was not to wage war, but to plant corn and re-establish their presence on their ancestral lands, hoping that the sheer act of return would be enough to deter further encroachment.

However, the U.S. government and the Illinois militia interpreted this movement as an invasion. The ensuing conflict saw a series of skirmishes, tactical retreats by Black Hawk’s band, and increasingly brutal pursuit by U.S. forces, which included regular army troops under Generals Henry Atkinson and Winfield Scott, as well as volunteer militias that boasted future presidents Abraham Lincoln and Zachary Taylor, and future Confederate president Jefferson Davis, among their ranks.

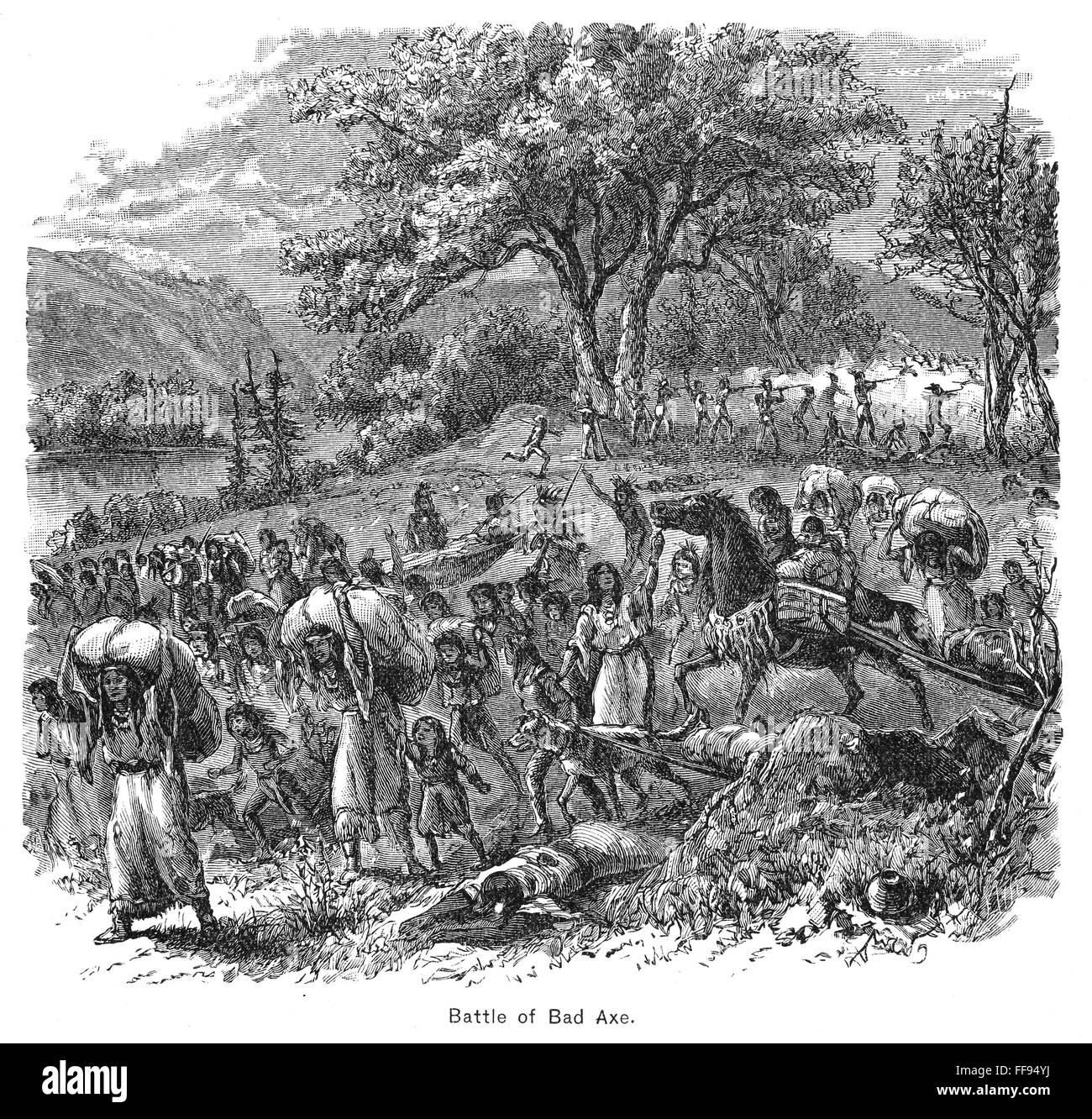

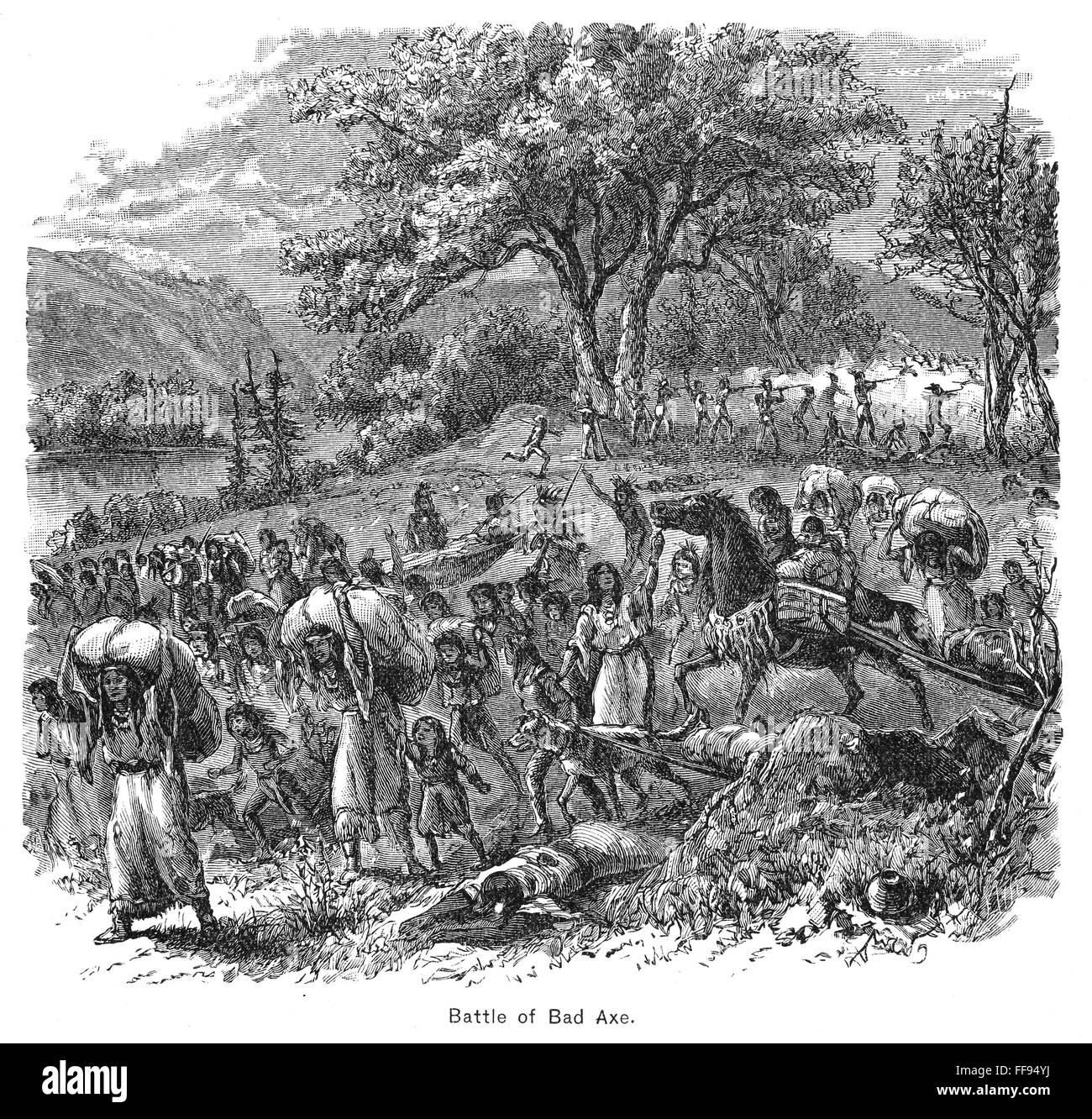

The Slaughter at Bad Axe: A War of Extermination

The true horror of the Black Hawk War culminated on August 1-2, 1832, at the Battle of Bad Axe. Having been relentlessly pursued and starved, Black Hawk’s band attempted to cross the Mississippi River near the mouth of the Bad Axe River in present-day Wisconsin, hoping to reach safety in Iowa Territory. What followed was less a battle and more a massacre. As the exhausted and starving Native Americans, many of them non-combatants, tried to ferry across the river, U.S. troops and militia opened fire indiscriminately from the bluffs, while a U.S. steamboat, the Warrior, shelled them from the river.

Eye-witness accounts describe scenes of unimaginable brutality. Men, women, and children were shot as they swam, clubbed to death as they reached the shore, or drowned in the river. Estimates vary, but between 250 and 400 Native Americans were killed, while U.S. casualties were minimal, numbering around 26 throughout the entire war. One militiaman, Lieutenant Robert Anderson (later a Union general at Fort Sumter), wrote, "It was a horrid sight to witness so many women and children, as well as brave warriors, so unfeelingly slaughtered." The Bad Axe Massacre effectively ended the Black Hawk War, sealing the fate of Black Hawk’s band and setting a grim precedent for future conflicts between settlers and Native Americans.

Immediate Aftermath: Land Cession and Forced Migration

The most immediate and devastating impact of the war was the massive loss of land. In the wake of the defeat, Black Hawk was captured and paraded across the country as a symbol of conquered savagery. The Treaty of Fort Armstrong, signed in September 1832, forced the Sauk and Meskwaki to cede yet another vast territory – some 6 million acres in what became known as the "Black Hawk Purchase." This immense tract, encompassing much of eastern Iowa and parts of western Illinois, was opened for white settlement. For the Sauk, this was not just a loss of territory, but a profound severing from their ancestral homeland, their hunting grounds, their sacred sites, and the graves of their forebears.

The defeat also solidified the power of Chief Keokuk, who had advocated for peace and accommodation, over Black Hawk’s more resistant faction. While Keokuk’s diplomacy likely saved his people from further direct military confrontation, it came at the cost of immense land cessions and a diminished sense of self-determination.

With their traditional lands gone, the Sauk were forced to relocate, first to temporary reservations in Iowa, then progressively westward into Kansas, and finally, for many, to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in the 1860s. This forced migration, often accompanied by disease, starvation, and exposure, was a traumatic experience, echoing the "Trail of Tears" endured by southeastern tribes. Each move further alienated them from their cultural roots and disrupted their social structures.

Cultural Erosion and the Fight for Survival

Beyond the immediate loss of life and land, the Black Hawk War inflicted deep and lasting wounds on the Sauk Nation’s cultural fabric. The traditional cycle of life – hunting, farming, ceremonies tied to specific seasons and places – was shattered. The buffalo, central to their diet and culture, were rapidly disappearing due to white hunters. The U.S. government, through its Indian agents, actively promoted assimilation, encouraging farming, Christian conversion, and the adoption of American clothing and customs. Sauk children were sent to boarding schools where their languages were forbidden and their traditional spiritual beliefs suppressed.

The trauma of the war and subsequent displacement led to a period of profound social dislocation. Alcoholism, disease, and internal strife became prevalent on the reservations. The Sauk, once a powerful and unified nation, found themselves reduced to wards of the state, dependent on government annuities for survival. Their political structures were undermined, as the U.S. government often empowered "chiefs" who were compliant with American policies, further eroding traditional forms of governance.

However, amidst this adversity, the Sauk people demonstrated remarkable resilience. Despite immense pressure, many continued to practice their traditional ceremonies in secret, pass down their language and stories, and maintain their kinship ties. Oral histories kept the memory of Saukenuk alive, a constant reminder of what was lost and a source of strength for the future.

A Divided Nation: Iowa vs. Oklahoma

The impact of the war also contributed to the physical division of the Sauk and Meskwaki people. While many were forcibly removed to Oklahoma, a significant number of Meskwaki, often referred to as Fox, were determined to return to their ancestral lands in Iowa. Through sheer persistence and by pooling resources, they legally purchased a small tract of land near Tama, Iowa, in the 1850s, creating the Meskwaki Settlement. This act of self-determination was unprecedented and remarkable, establishing a community that, while facing its own challenges, maintained a greater degree of cultural autonomy than many of their relatives in Oklahoma.

Today, the descendants of the Sauk and Meskwaki are primarily organized into three federally recognized tribes: the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma, the Sac and Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa (Meskwaki Nation), and the Sac and Fox Nation of Missouri in Kansas and Nebraska. While they share a common heritage, their distinct histories post-1832 have led to unique cultural expressions and political trajectories. The war, therefore, not only dispossessed them of land but also fundamentally altered their communal geography and political landscape.

The Enduring Legacy: Resilience and Remembrance

The Black Hawk War remains a potent symbol for the Sauk Nation. It is a story of profound loss – of land, life, and sovereignty – but also a testament to their enduring spirit and resistance. Modern Sauk and Meskwaki communities are actively engaged in language revitalization programs, cultural preservation efforts, and the assertion of their tribal sovereignty. They operate their own governments, schools, and businesses, striving to build strong, self-sufficient nations.

The memory of Black Hawk, once demonized as a rogue warrior, has been reclaimed by his people as a symbol of courageous defense of their heritage. His words from his autobiography resonate with enduring power: "What has been done cannot be undone. But the future can be shaped by the lessons of the past."

The Black Hawk War serves as a stark reminder of the complexities and injustices inherent in the formation of the United States. It highlights how land greed and cultural misunderstanding led to catastrophic consequences for Indigenous peoples. The war did not just end in 1832; its impacts reverberated through generations, shaping federal Indian policy, land tenure, and the very identity of the Sauk Nation. Understanding this conflict is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for recognizing the historical trauma that Indigenous communities continue to navigate and for appreciating their remarkable resilience in the face of centuries of adversity. The echoes of Black Hawk’s stand continue to demand attention, urging a deeper understanding of American history and a renewed commitment to justice for its first peoples.