The Enduring Spirit of the Nimiipuu: Exploring Nez Perce Spiritual Practices

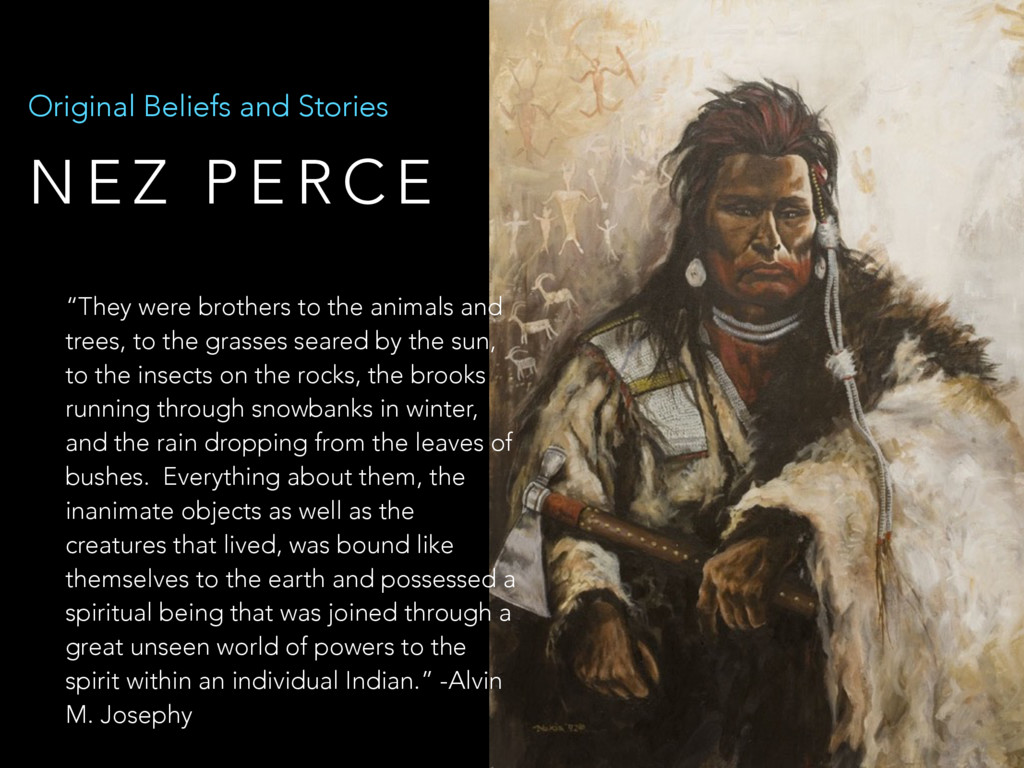

The wind whispers through the Wallowa Valley, a sacred breath carrying echoes of a time when the Nimiipuu – "The People," known to the world as the Nez Perce – lived in an unbroken harmony with their ancestral lands. For this resilient Indigenous nation of the Pacific Northwest, spirituality was never a separate compartment of life, but the very fabric of their existence, interwoven with every sunrise, every river stone, and every shared story around the fire. It was a spirituality rooted in an profound reverence for the natural world, a deep connection to the Creator, and an unyielding belief in the power of individual and communal spirit.

To understand Nez Perce spiritual practices is to grasp their concept of Tamánwit, a complex term encompassing not just "Creator" or "Great Spirit," but also "the law of the land," "the way," or "the teachings." It represents the inherent order of the universe, the moral code, and the sacred relationship between humans and all living things. This concept dictated their behavior, their ceremonies, and their very perception of reality. Every mountain, river, and plain held spiritual significance, not merely as resources, but as living entities, imbued with spirit and wisdom.

The Quest for Wéyekin: Individual Power and Purpose

At the heart of individual Nez Perce spiritual development was the vision quest, a deeply personal and transformative journey undertaken by young people, typically around puberty. Sent out alone into the wilderness, often to remote and sacred sites, they would fast, meditate, and pray, seeking a spiritual guardian or Wéyekin (also spelled Weeyekkin). This Wéyekin could manifest as an animal, a plant, a natural phenomenon like lightning or a storm, or even an ancestral spirit.

The encounter with a Wéyekin was not merely a dream; it was a profound spiritual experience that imparted a unique power, a specific song, a personal name, and guidance for one’s life path. A person’s Wéyekin determined their strengths, their spiritual gifts, and their role within the community – whether they would become a skilled hunter, a wise leader, a powerful healer, or a renowned storyteller. This personal power was not for selfish gain but was meant to be used for the benefit of the family and the tribe. It was a lifelong connection, a source of wisdom and strength that could be called upon in times of need.

Communal Rites: Cycles of Purification and Gratitude

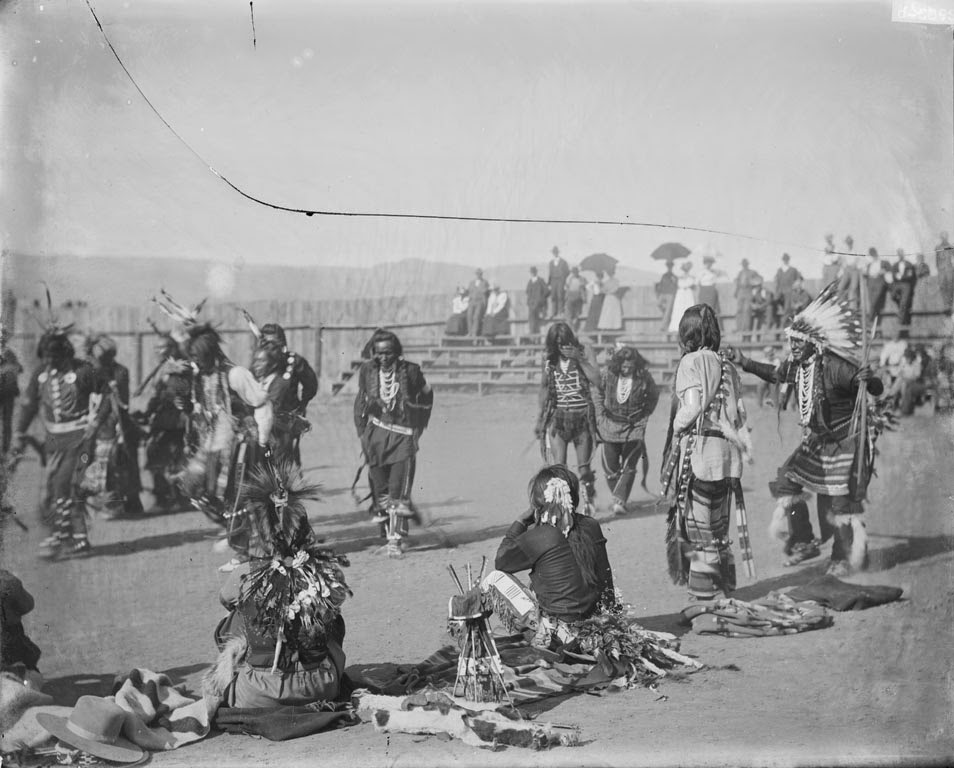

While individual quests were vital, communal ceremonies reinforced the tribal bonds and their collective spiritual identity. The Sweat Lodge, or Ch’k’u’q’a, was (and remains) a central ritual of purification and prayer. Constructed from natural materials – a dome of willow branches covered with hides or blankets – it replicated the womb of Mother Earth. Heated stones placed in a central pit would release steam when water was poured over them, creating an intense, dark, and purifying environment. Inside, participants would pray, sing sacred songs, and offer thanks, shedding physical and spiritual impurities. It was a space for healing, contemplation, and reconnection with the Creator and the community.

Seasonal ceremonies, particularly the First Foods Feasts, were expressions of profound gratitude and respect for the bounty of the earth. The Nez Perce traditionally relied on a rich diet of fish (especially salmon), game, and various roots and berries. The first harvest of camas roots (a staple food), kouse, huckleberries, and the return of the salmon were celebrated with elaborate ceremonies. These feasts involved prayers, traditional songs, dances, and sharing the first catches or harvests. They were not just meals but sacred acknowledgements of the Creator’s generosity and the interconnectedness of all life, reinforcing their role as stewards of the land.

The Power of Story and Song: Weaving Tradition

Nez Perce spirituality was also deeply embedded in their oral traditions. Storytelling was a vital means of transmitting knowledge, values, and spiritual teachings across generations. Elders were the custodians of these narratives, recounting tales of creation, the adventures of the Trickster Coyote (Isi), and historical events. Coyote, often portrayed as a mischievous but ultimately benevolent figure, was central to many Nez Perce myths. He was responsible for shaping the world, teaching humans survival skills, and sometimes, through his mistakes, illustrating moral lessons.

These stories were more than entertainment; they were living texts that taught children about Tamánwit, the importance of respecting nature, the consequences of greed, and the virtues of courage and community. Songs, too, held immense spiritual power. Passed down through families or received during vision quests, they were used in ceremonies, for healing, for hunting, and for expressing emotions. Each song carried its own energy and purpose, a direct line to the spiritual realm.

Dreamer-Prophets and the Struggle for Sovereignty

As Euro-American settlers encroached upon their lands in the 19th century, Nez Perce spiritual practices became a source of strength and resistance. The rise of Dreamer-Prophets like Smohalla and Too-hul-hul-sote marked a significant spiritual movement. These prophets, often having experienced powerful visions, preached a return to traditional ways, emphasizing the sacredness of the land and rejecting assimilation.

Too-hul-hul-sote, a powerful Wallowa Nez Perce spiritual leader, vehemently opposed the U.S. government’s demands to confine his people to a reservation. His defiance stemmed directly from his spiritual convictions. In a famous exchange with General Oliver O. Howard in 1877, Too-hul-hul-sote declared, "The earth is my mother, and I cannot sell the earth. I will not sell a part of my country, nor my country itself. Did not my ancestors live on this land as long as the grass grows?" This powerful statement encapsulated the Nez Perce spiritual connection to their homeland – a relationship that transcended mere ownership and was instead about kinship and stewardship.

The tragic Nez Perce Flight of 1877, led by Chief Joseph, Looking Glass, White Bird, and others, was not just a military retreat but a profound spiritual journey. For over a thousand miles, pursued by the U.S. Army, the Nez Perce carried their spiritual practices with them. Despite immense hardship, they continued to hold ceremonies, pray, and draw strength from their ancestral beliefs. The famous surrender speech of Chief Joseph, "I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed… From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever," was a moment of profound spiritual exhaustion and sacrifice, not a renunciation of their beliefs, but a pragmatic decision born of the desire to preserve the remaining lives of his people.

Resilience and Revitalization in the Modern Era

The forced removal and subsequent attempts at assimilation, including the outlawing of many Indigenous spiritual practices, dealt severe blows to Nez Perce culture. However, the spirit of the Nimiipuu endured. Many practices went underground, passed down in secret, preserving the core of their spiritual heritage.

Today, Nez Perce spiritual practices are experiencing a powerful resurgence. The Nez Perce Tribe (Nimiipuu Tribal Executive Committee) actively works to revitalize their language (Nez Perce or Niimiipuutímt), traditional ceremonies, and cultural arts. Younger generations are learning the ancient songs, participating in sweat lodge ceremonies, and reconnecting with the land. The First Foods Feasts are celebrated openly, reinforcing communal bonds and environmental stewardship. The wisdom of the elders continues to guide the community, ensuring that the Tamánwit remains a living force.

The enduring spirit of the Nez Perce stands as a testament to the profound power of a people deeply rooted in their sacred earth. Their spiritual practices, born of respect, gratitude, and an intimate relationship with the natural world, continue to offer lessons in resilience, interconnectedness, and the timeless pursuit of harmony – a harmony that resonates through the Wallowa Valley and far beyond, inviting all to listen to the whispers of the land.