Echoes of the Plains: The Enduring Cultural Tapestry of the Comanche Nation

LAWTON, Oklahoma – The name "Comanche" often conjures images of fearsome warriors thundering across the Great Plains on horseback, masters of buffalo hunting and formidable adversaries. While these images hold a kernel of truth, they merely scratch the surface of a deeply rich, complex, and enduring culture that, despite centuries of immense pressure, continues to thrive. Beyond the historical narratives of conquest and conflict lies a vibrant tapestry of practices, beliefs, and traditions that define the Numunuu, "The People," as the Comanche call themselves.

To understand Comanche cultural practices is to understand a people intrinsically linked to the land, the horse, and the buffalo – a trinity that shaped their identity, social structures, and spiritual worldview for generations. From their origins as a small band of Shoshone speakers in the northern Rockies, the Comanche migrated south, acquiring horses in the early 1700s and transforming into the dominant power on the southern plains, establishing an empire known as Comancheria.

The Horse and the Buffalo: Pillars of Existence

The acquisition of the horse was a pivotal moment, revolutionizing every aspect of Comanche life. It allowed them to hunt buffalo with unparalleled efficiency, travel vast distances, conduct raids, and defend their territory. "The horse wasn’t just a tool; it was family, it was power, it was life itself for us," explains LaDonna Brown, a Comanche Nation tribal elder and cultural preservationist. "Without the horse, we couldn’t have been the Numunuu we became."

The buffalo, in turn, provided everything. Its meat was their primary sustenance, its hide used for tipis, clothing, shields, and moccasins. Bones became tools, sinew for thread, and dung for fuel. This symbiotic relationship fostered a profound respect for nature and an understanding of sustainability long before the term was coined. Hunting was not merely a means of survival but a spiritual endeavor, often preceded by prayers and rituals to honor the animal’s sacrifice. The annual buffalo hunt was a communal event, strengthening social bonds and reinforcing collective identity.

Social Structure and Kinship: The Strength of the Bands

Comanche society was organized into autonomous, fluid bands, each led by a chief whose authority was based on skill, wisdom, and success in warfare or hunting. While no central government existed among the bands, kinship ties were paramount. Extended families formed the bedrock of society, with strong emphasis on mutual support and loyalty. Children were raised communally, taught by elders, and encouraged to develop self-reliance and bravery.

Gender roles, though distinct, were complementary and equally vital. Men were primarily hunters, warriors, and protectors, responsible for providing food and defending the band. Women were the heart of the home, responsible for setting up and dismantling tipis, preparing food, tanning hides, crafting clothing, and raising children. Their intricate beadwork, quillwork, and parfleche designs were not just decorative but often carried spiritual significance and served as a form of artistic expression and historical record. "Our grandmothers were the backbone," says cultural educator Ronald Red Elk. "They kept the camp running, they passed down the stories, they ensured our survival every single day."

Spirituality and Worldview: Connecting with the Sacred

Comanche spirituality was deeply intertwined with the natural world. They believed in a Creator, often referred to as the Great Spirit or the Great Mystery, and that spirits inhabited all living things and natural phenomena. Visions were highly valued, sought through solitary quests and fasting, providing guidance and spiritual power (puha). Animal spirits, particularly the eagle and the bear, held special significance as sources of strength and wisdom.

The Sun Dance, though practiced by some Comanche bands, was more central to their northern Plains neighbors. For the Comanche, other ceremonies and individual spiritual practices were more prominent. The Native American Church, incorporating the ritual use of peyote, gained significant traction among the Comanche and other Plains tribes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It provided a spiritual haven and a means of cultural continuity during periods of intense assimilation pressure. Participants gather in a tipi, sing sacred songs, pray, and consume peyote as a sacrament, seeking spiritual insight, healing, and connection to the divine.

Warfare and Diplomacy: A Complex Legacy

The Comanche’s reputation as fierce warriors is well-deserved. Their mastery of mounted warfare made them virtually unstoppable on the plains. Raids were not solely about violence but often served strategic purposes: acquiring horses, captives (who were often adopted into the tribe), or avenging wrongs. Their war parties were highly disciplined, employing complex tactics and communication signals.

However, their history is also rich with diplomacy. The Comanche engaged in extensive trade networks, exchanging buffalo products, horses, and captives with Pueblo peoples, Wichitas, and later, Anglo-Americans and Mexicans. They formed alliances when it suited their interests and meticulously negotiated treaties, though these were often broken by encroaching settlers and governments. Quanah Parker, the last principal chief of the Kwahadi Comanche and a pivotal figure in the transition to reservation life, epitomized this blend of warrior spirit and diplomatic acumen, advocating for his people’s rights and adapting to a changing world.

Oral Tradition and Language: The Voice of the Ancestors

Like many Indigenous cultures, the Comanche relied heavily on oral tradition to transmit knowledge, history, and values across generations. Storytelling was a vital practice, often taking place around campfires, where elders recounted creation myths, heroic deeds, cautionary tales, and practical wisdom. These narratives instilled moral lessons, reinforced cultural norms, and preserved the collective memory of the Numunuu.

The Comanche language, Nʉmʉ tekwapʉ, a Uto-Aztecan language, is a critical component of their identity. While it faced severe decline due to forced assimilation policies that prohibited its use in schools, there is a strong revitalization effort underway today. The Comanche Nation offers language classes, develops educational materials, and encourages its use in homes and communities. "Our language carries our worldview, our humor, our specific way of seeing the world," says Brown. "To lose it is to lose a piece of our soul. We are fighting hard to bring it back."

Adaptation and Resilience: The Modern Comanche Nation

The late 19th century brought cataclysmic changes. The decimation of the buffalo herds, the relentless pressure of the U.S. Army, and the forced relocation to reservations in Oklahoma marked a brutal period of cultural disruption. Traditional ways of life were suppressed, children were sent to boarding schools where their language and customs were forbidden, and land was allotted, breaking up communal holdings.

Yet, the spirit of the Numunuu persisted. Today, the Comanche Nation, headquartered in Lawton, Oklahoma, is a federally recognized sovereign tribe with a vibrant community. While many traditional practices have evolved or been adapted, the core values of kinship, respect for elders, connection to the land, and cultural pride remain strong.

Contemporary cultural practices include:

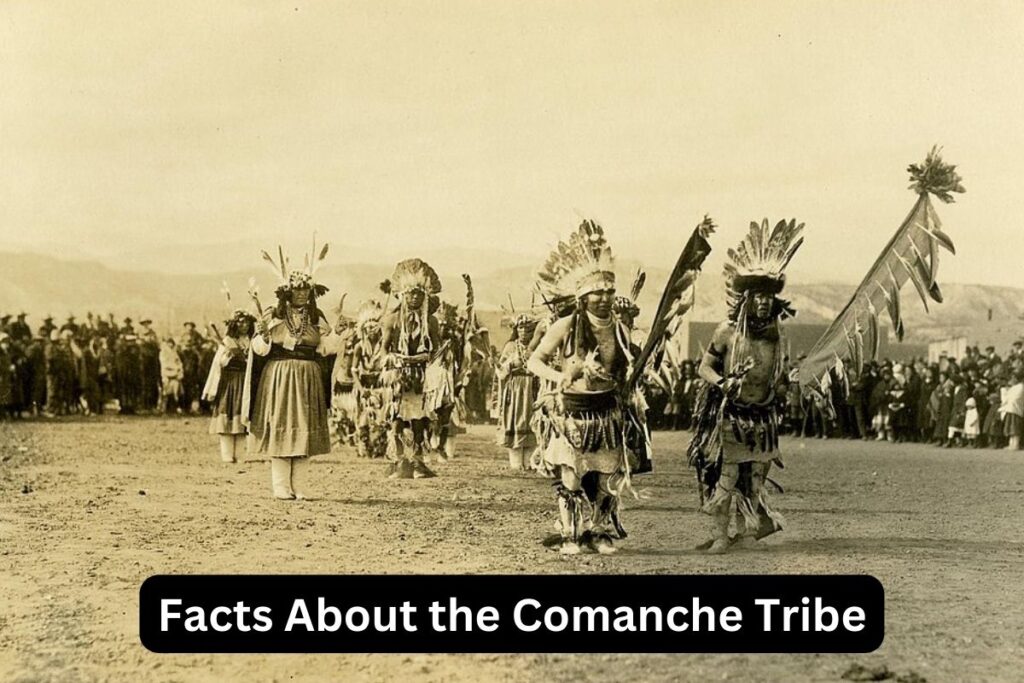

- Powwows: These intertribal gatherings are vibrant celebrations of Native American culture, featuring traditional dances, drumming, singing, and regalia. They are a powerful way for Comanche people to connect with their heritage, share their culture, and honor their ancestors.

- Language Revitalization Programs: Intensive efforts are being made to teach the Comanche language to younger generations through classes, immersion programs, and digital resources.

- Cultural Preservation Centers: The Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center in Lawton serves as a hub for preserving artifacts, sharing history, and hosting cultural events and educational programs.

- Traditional Arts and Crafts: Artists continue to create beadwork, pottery, regalia, and other traditional crafts, often incorporating contemporary elements while honoring ancestral techniques.

- Ceremonial Practices: While some ceremonies are private, others, like specific dances or healing practices, continue within the community, often adapted to modern contexts but retaining their spiritual essence.

- Veterans’ Honoring: The Comanche have a long and proud history of military service, from their warrior ancestors to modern-day soldiers. Honoring veterans is a significant cultural practice, recognizing their bravery and sacrifice.

The story of Comanche cultural practices is one of extraordinary resilience. From being "Lords of the Plains" to enduring profound hardship, the Numunuu have not only survived but continue to assert their identity and heritage. "Our ancestors faced immense challenges, but they never forgot who they were," reflects Red Elk. "Their strength flows through us. We are still here, still Comanche, still strong." The echoes of the plains continue to resonate, carried forward by a people determined to ensure their unique cultural tapestry remains vibrant for generations to come.