Echoes in Cedar and Stone: The Enduring Power of Haida Traditional Arts

On the rugged, mist-shrouded islands of Haida Gwaii, where ancient cedars pierce the sky and the Pacific Ocean roars against a dramatic coastline, an extraordinary artistic tradition has flourished for millennia. This is the ancestral home of the Haida Nation, and their art – vibrant, intricate, and deeply spiritual – is far more than mere decoration. It is a living language, a historical record, a spiritual conduit, and the very heartbeat of a resilient people. Haida traditional arts, with their distinctive formline designs and profound narratives, stand as a testament to ingenuity, cultural continuity, and an unbreakable connection to the natural world.

From monumental totem poles that stand sentinel over villages to exquisitely carved argillite miniatures, from functional bentwood boxes to ceremonial masks and intricately woven textiles, Haida art embodies a sophisticated visual vocabulary. It speaks of the cosmos, of animal spirits, of ancestral lineages, and of the fundamental balance between the human and natural realms.

The Visual Language: Formline and its Philosophy

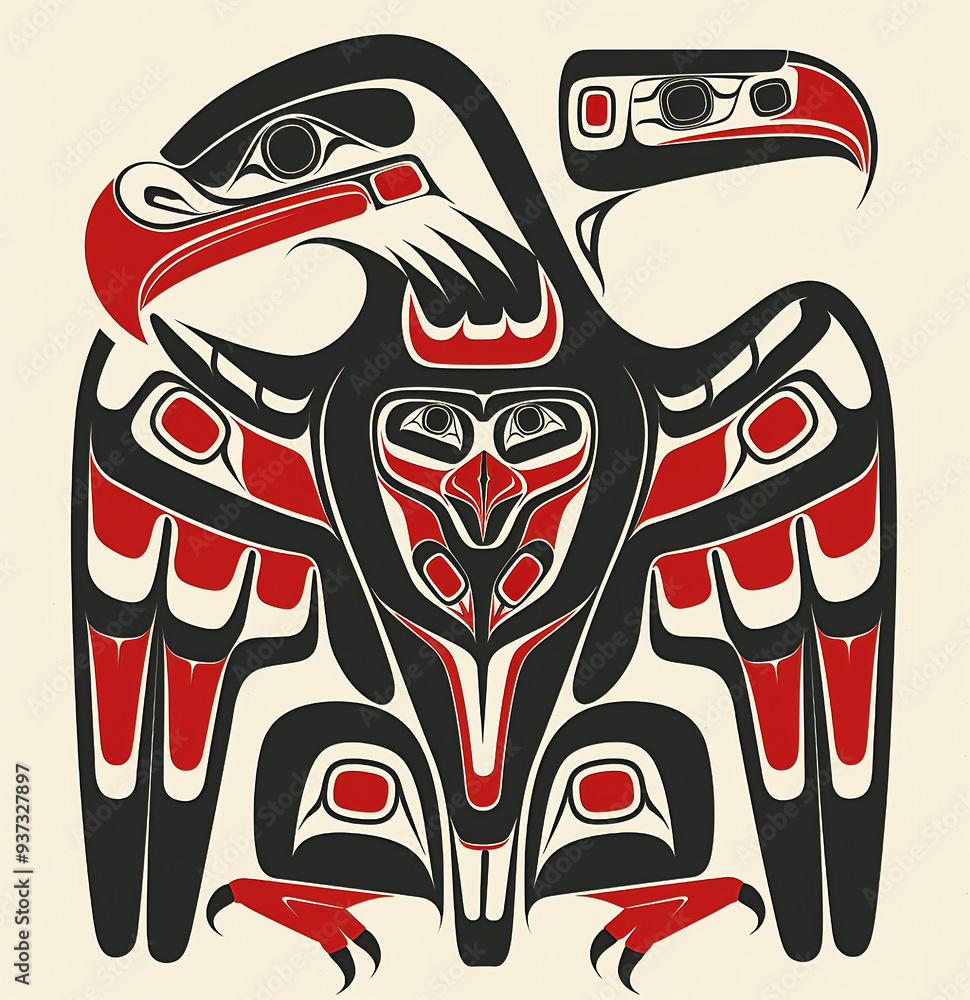

At the core of Haida art lies the unique and complex system known as "formline." This is not simply a style but a highly structured grammatical system of design. Characterized by swelling and tapering lines, ovoids, U-forms, and S-forms, formline creates a dynamic flow, allowing artists to render figures—often animal crests like Raven, Eagle, Bear, and Killer Whale—with incredible fluidity and symbolic depth. These elements are not just outlines; they are active components that define and connect shapes, creating a sense of movement and interconnectedness.

"Formline is a visual language," renowned Haida artist Robert Davidson once stated, emphasizing its capacity to convey complex ideas and narratives. "It carries the same power as the spoken word, but it’s seen. It’s a language of our people." This system allows for the decomposition and recomposition of figures, where eyes, joints, and internal organs are often depicted as independent ovoids or U-forms, creating a sense of transparency and revealing the inner spirit or essence of the being. This artistic convention reflects a worldview where the visible and invisible worlds are intertwined, and where the boundaries between human and animal are fluid, allowing for transformation and spiritual journeys.

Sentinels of Stories: The Totem Poles

Perhaps the most iconic manifestation of Haida art is the monumental totem pole. Carved from the majestic red and yellow cedars that abound on Haida Gwaii, these towering structures are not objects of worship but powerful storytellers, mnemonic devices, and statements of lineage and prestige. Each figure carved into a pole represents a crest, an ancestral being, or a significant event in a family’s history, often rooted in origin myths or epic sagas.

Historically, totem poles served various purposes: memorial poles commemorated the deceased; mortuary poles housed the remains of chiefs; house frontal poles marked the entrance to important longhouses; and interior house posts supported massive roof beams, often depicting ancestral figures. The raising of a pole was a momentous occasion, accompanied by elaborate potlatches—feasts and ceremonies where wealth was distributed, and rights and privileges were publicly affirmed. The poles, therefore, were public declarations, visible markers of identity, history, and status within the community.

The process of carving a pole was itself a profound act of collaboration and spiritual engagement, often taking years. Master carvers, apprentices, and community members worked together, honoring the spirit of the tree and imbuing the wood with the narratives it would forever bear. These poles, weathering the elements, gradually return to the earth, a natural cycle that mirrors the transient nature of life, yet their stories endure through oral tradition and new carvings.

The Black Slate: Argillite Carvings

In striking contrast to the monumental scale of totem poles are the exquisite carvings made from argillite, a unique black slate found only on Haida Gwaii, specifically at Slatechuck Creek. This soft, fine-grained stone allows for incredibly intricate detail, making argillite carvings prized possessions. Early carvings, often pipes, became highly sought after by European traders and sailors in the 19th century, serving as an early form of economic exchange and cultural bridge.

Argillite carvings range from small figures of animals and mythological beings to complex "sg_aang_gwa" (pole-like carvings) depicting multiple figures, often with a mischievous or satirical edge. The dark, lustrous surface of the polished argillite beautifully highlights the flowing lines and delicate forms, creating a captivating interplay of light and shadow. The skill required to work this material is immense, demanding precision and patience, as one wrong cut can shatter the piece. Haida artists have transformed this unique geological resource into a globally recognized art form, demonstrating their adaptability and artistic genius.

Beyond Carving: Masks, Weaving, and More

Haida traditional arts extend far beyond wood and stone. Masks, carved from wood and often adorned with abalone shell, human hair, and paint, were central to ceremonial performances. These masks could depict human faces, animal spirits, or transformative beings, often designed with moving parts to reveal a spirit changing from one form to another. They were not merely costumes but powerful conduits for spiritual connection, allowing dancers to embody the characters of myths and bring ancestral stories to life during potlatches and other ceremonies.

Weaving, primarily done by Haida women, also holds a place of immense cultural significance. Spruce root and cedar bark were meticulously prepared and woven into a variety of practical and ceremonial items: hats, baskets, cloaks, and particularly the magnificent "Naaxin" or Chilkat blankets. These blankets, characterized by their flowing, curvilinear designs often featuring abstracted animal forms, were woven using a unique twining technique that allowed for complex patterns to be incorporated directly into the fabric. The "button blanket," a later innovation, integrated European trade cloth and mother-of-pearl buttons into striking crest designs, serving as regalia for chiefs and dancers.

Canoes, essential for travel, trade, and whaling, were also magnificent works of art. Carved from single cedar logs, these vessels were designed for speed and stability, often adorned with painted crests and sculptural elements on the bow and stern, reflecting the Haida’s profound relationship with the ocean.

The Shadow of Colonialism and the Light of Resurgence

The vibrant trajectory of Haida art, like that of many Indigenous cultures, faced immense challenges with the arrival of European settlers. The imposition of colonial laws, the devastating impact of diseases, and particularly the Canadian government’s ban on the Potlatch ceremony (from 1884 to 1951) – a cornerstone of Haida social and artistic life – pushed many traditional art forms to the brink of extinction. Without the ceremonial context for their creation and use, and with children forcibly removed to residential schools where their language and culture were suppressed, the intergenerational transmission of artistic knowledge was severely disrupted.

"Our art was considered pagan, an obstacle to civilization," noted a Haida elder, reflecting on the dark period. Many master artists passed away without having been able to fully transmit their knowledge to a new generation. Pieces were confiscated and sold to museums and private collectors worldwide, further disconnecting the art from its people.

However, the spirit of Haida art proved too resilient to be extinguished. In the mid-20th century, a remarkable resurgence began, spearheaded by a few dedicated individuals. Bill Reid (1920-1998), a Haida artist of mixed Haida and European ancestry, played a pivotal role. Though initially trained in mainstream art forms, Reid committed himself to understanding and mastering the traditional Haida formline. He meticulously studied old pieces in museum collections, drawing upon the knowledge of elders and working to breathe new life into the dying tradition. His monumental sculptures, like "The Raven and the First Men" and "Spirit of Haida Gwaii," are iconic works that blend traditional forms with contemporary artistic vision, bringing Haida art to a global audience.

Following Reid, another luminary emerged: Robert Davidson (b. 1946). As a young man, Davidson was instrumental in the revival of pole carving on Haida Gwaii, raising the first new totem pole in his village of Massett in nearly a century in 1969. This act was a powerful declaration of cultural renewal. Davidson, like Reid, dedicated his life to mastering the traditional formline and, crucially, to teaching it to new generations of Haida artists. He established apprenticeships, ensuring that the intricate knowledge of carving, painting, and design would be passed on, securing the future of the art form.

A Living Legacy: Identity and Future

Today, Haida traditional arts are experiencing a powerful renaissance. A new generation of Haida artists, building upon the foundations laid by Reid and Davidson, continues to innovate while deeply respecting traditional principles. They are exploring new mediums, incorporating contemporary themes, and pushing the boundaries of what Haida art can be, all while staying firmly rooted in the ancestral visual language.

Haida art remains inextricably linked to Haida identity, sovereignty, and the ongoing work of cultural revitalization. It is a powerful tool for education, for economic development, and for asserting the nation’s unique place in the world. Art galleries and cultural centers on Haida Gwaii and beyond showcase contemporary Haida works, while cultural programs ensure that the skills of carving, weaving, and design are taught to children and youth.

The art itself is a constant reminder of the Haida relationship with Haida Gwaii—the land, the sea, and the spirits that inhabit them. It is a visual affirmation of their worldview, their history, and their enduring connection to their ancestors. As the mist continues to swirl around the ancient cedars of Haida Gwaii, the echoes of the carver’s adze and the weaver’s shuttle resonate, a testament to the enduring power and living legacy of Haida traditional arts—a profound language that continues to speak across generations, telling stories of resilience, beauty, and the unbreakable spirit of a nation.