Echoes of Apsáalooke: The Enduring Fight for the Crow Language

The wind whispers across the vast plains of Montana, carrying not just the scent of sagebrush and pine, but the faint echoes of a language as old as the mountains themselves. It is the language of the Apsáalooke, or Crow people, a vibrant and complex tongue that for centuries served as the heartbeat of a proud nation. Today, however, these echoes are growing fainter, threatened by a tide of assimilation that has steadily eroded indigenous languages across the globe. Yet, amidst this decline, a powerful movement is rising, driven by elders, educators, and a new generation determined to ensure that the voice of the Apsáalooke endures.

The Crow language, a member of the Missouri River Siouan family, is far more than just a means of communication; it is a living repository of culture, history, and an entire worldview. Its structure, intricate and nuanced, reflects the Apsáalooke relationship with the land, their spiritual beliefs, and their social organization. Unlike English, Crow is a polysynthetic language, meaning words are often formed by combining many morphemes (meaningful units), creating highly descriptive and precise expressions. A single Crow word can convey a concept that might require an entire sentence in English.

"When we speak Crow, we’re not just speaking words; we’re speaking our ancestors, our land, our very identity," explains Dr. Janine Pease, a respected Crow elder and educator. "Every sound, every syllable, carries the weight of generations. To lose our language is to lose a part of our soul, a unique way of understanding the world that no other language can replicate." This intrinsic link between language and identity is precisely what makes its preservation a matter of cultural survival, not just linguistic curiosity.

The journey towards endangerment for the Crow language, like many other Indigenous tongues in North America, is a tragic chapter born from policies of forced assimilation. The late 19th and 20th centuries saw the systematic dismantling of Native American cultures, with language at the forefront of the attack. Boarding schools, established by the U.S. government and religious institutions, became instruments of cultural genocide. Native children were forcibly removed from their homes, forbidden from speaking their native languages, and often punished severely for doing so.

"My grandmother told me stories of having her mouth washed out with soap for speaking Crow," recalls Robert Yellowtail Jr., a Crow tribal historian. "They wanted to ‘kill the Indian to save the man,’ and the first thing they killed was our language. Generations grew up without learning their mother tongue, either because their parents were punished for speaking it, or because they feared their children would suffer the same fate." This intergenerational trauma created a devastating breach in the natural transmission of language, leading to a precipitous decline in fluency.

Today, the numbers paint a stark picture. While the Crow Tribe numbers over 13,000 enrolled members, the number of fluent Crow speakers is estimated to be less than 4,000, with the vast majority being elders over the age of 60. This demographic reality means that time is of the essence. As the fluent elder population diminishes, so too does the direct, living connection to the language’s nuances, its idiomatic expressions, and its cultural context.

Recognizing this critical juncture, the Crow Nation has embarked on an ambitious and multifaceted mission to revitalize Apsáalooke. At the heart of this effort are immersion programs designed to cultivate new generations of fluent speakers.

One of the most promising initiatives is the Apsáalooke Language Immersion School (ALIS) in Lodge Grass, Montana. Founded on the principle that full immersion is the most effective way to learn a language, ALIS offers an environment where children are steeped in Crow from their first steps into the classroom. From morning greetings to lessons in math and science, every interaction is conducted in Apsáalooke.

"It’s challenging, no doubt," says Sara Old Coyote, a young teacher at ALIS, her voice brimming with passion. "Many of our students come in with very little exposure to Crow, but their minds are like sponges. You see their eyes light up when they grasp a new concept, not just in English, but in their ancestral language. It’s not just teaching words; it’s teaching a way of seeing the world, a Crow way of knowing." The school aims to produce students who are not only fluent but also culturally grounded, understanding the values and traditions embedded within the language.

Beyond formal schooling, community-led initiatives are equally vital. Master-apprentice programs pair fluent elders with dedicated learners, fostering one-on-one mentorships that allow for intensive, personalized language acquisition. These programs often take place in everyday settings – cooking, gardening, or working on traditional crafts – mimicking the natural way language is learned in a home environment.

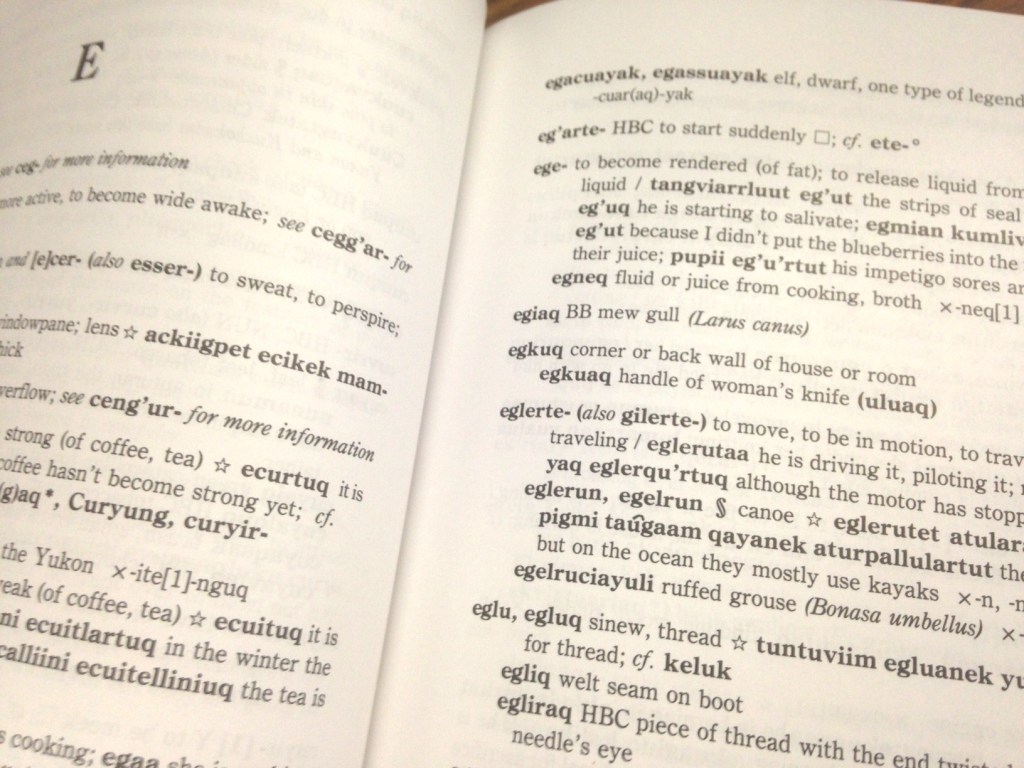

Technology has also emerged as a powerful ally in the revitalization effort. The Crow Language Consortium, in partnership with various universities and organizations, has developed online dictionaries, phrasebooks, and interactive learning apps, making the language more accessible to learners both on and off the reservation. Social media platforms are increasingly used by younger Crow people to share phrases, songs, and cultural content in Apsáalooke, creating virtual spaces for language practice and community building.

"We have an app now, ‘Crow Language,’ that I use all the time," shares Marcus Three Irons, a 22-year-old Crow college student who is determined to become fluent. "It’s so cool to have that resource on my phone. My grandparents are so proud when I try to speak with them, even if I make mistakes. This language connects me to them, to my history, to who I really am." His sentiment echoes a growing awareness among younger Crow people of the profound importance of their linguistic heritage.

Despite these inspiring efforts, significant challenges remain. Funding for language programs is often precarious, relying on grants and donations that can fluctuate. There is a pressing need to train more qualified Crow language teachers, as the pool of fluent speakers willing and able to teach is limited. Furthermore, the pervasive influence of English-language media and mainstream culture presents a constant gravitational pull, often making it difficult to maintain consistent immersion outside of structured programs.

"It’s a race against time, truly," states Dr. Pease, her expression thoughtful. "Every elder we lose is like losing a library. But the spirit of our people is strong. We are a resilient people, and our language is a testament to that resilience. It’s not about going back in time; it’s about bringing the wisdom of our past into our future, ensuring our children and grandchildren can choose to speak their heritage."

The revitalization of the Crow language is more than just an academic exercise; it is an act of cultural sovereignty and self-determination. It is a defiant stand against centuries of oppression, a reclaiming of identity that was once systematically stripped away. Every word spoken in Apsáalooke, every song sung, every story told, is a victory. It reinforces the unique worldview of the Apsáalooke people, ensuring that their intricate relationship with the land, their spiritual practices, and their profound wisdom continues to resonate through the generations.

As the sun sets over the Crow Agency, casting long shadows across the Bighorn Mountains, one can almost hear the ancient sounds carried on the breeze. These are not merely whispers of the past, but increasingly, the confident, growing voices of the future. The fight for the Crow language is an ongoing journey, a testament to the enduring spirit of a people determined to speak their truth, in their own powerful tongue, for all time. The Apsáalooke are not merely preserving words; they are ensuring their very existence.