The Echoes of Ancient Tongues: Unraveling the Rich Tapestry of Pueblo Language Dialects

For many, the word "Pueblo" conjures a singular image: ancient, earth-toned dwellings nestled in the vast landscapes of the American Southwest, inhabited by a unified people with shared traditions. While the architectural and cultural similarities among the various Pueblo communities are undeniable, this perception often masks a profound and vibrant truth: the Pueblo world is a stunning linguistic mosaic, a testament to centuries of distinct historical pathways and the enduring power of language as a marker of identity. Far from speaking a single "Pueblo language," these communities are home to an astonishing array of tongues, many of which are mutually unintelligible, representing entirely separate language families.

This linguistic diversity is one of the Southwest’s most remarkable, yet often overlooked, treasures. It challenges the common narrative of monolithic indigenous cultures, revealing instead a complex web of interactions, migrations, and independent developments. To understand the Pueblo peoples is, in part, to understand their languages – the very sinews of their unique worldviews, spiritual practices, and connection to the land.

A Confluence of Tongues: The Major Language Families

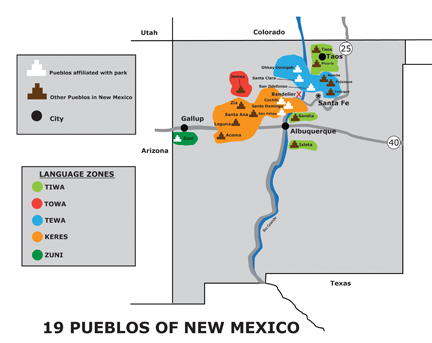

The approximately two dozen federally recognized Pueblo communities, primarily located in New Mexico and Arizona, speak languages belonging to no less than four distinct language families, along with two linguistic isolates. This makes the Pueblo region one of the most linguistically diverse areas in North America.

1. Tanoan Family: This is the largest and most widespread family among the New Mexico Pueblos, further divided into three main branches:

- Tiwa: Spoken at Taos, Picuris (Northern Tiwa), and Sandia and Isleta (Southern Tiwa). While they share a common ancestor, the Tiwa languages are not mutually intelligible across the northern and southern groups. A speaker from Taos, for example, would struggle to understand someone from Isleta without prior learning. Tiwa languages are known for their complex tonal systems and intricate verb morphology.

- Tewa: Spoken at Ohkay Owingeh (formerly San Juan), San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Nambe, Pojoaque, and Tesuque Pueblos. Tewa is relatively more mutually intelligible among its speakers, though dialectal differences exist. It is often described as having a rich oral tradition, with many stories and ceremonies preserved solely through spoken word.

- Towa: Spoken exclusively at Jemez Pueblo. Historically, Towa was also spoken at Pecos Pueblo, but that community eventually dwindled and its remaining members migrated to Jemez in the 19th century, integrating their language and culture. Towa is distinct from both Tiwa and Tewa, representing its own unique branch within Tanoan.

2. Keresan Family: This family is unique because it is not demonstrably related to any other language family, making its origins a subject of intense linguistic debate. Keresan languages are spoken at seven Pueblos: Cochiti, Santo Domingo (Kewa), San Felipe, Santa Ana, and Zia (Eastern Keresan), and Acoma and Laguna (Western Keresan). Like Tiwa, the Keresan languages are not mutually intelligible across their eastern and western branches, and even within branches, significant dialectal variations exist. Keresan languages are characterized by their complex phonology, including a wide array of glottalized and ejective consonants.

3. Zuni Language (Isolate): Spoken at Zuni Pueblo in western New Mexico, Zuni is a linguistic isolate, meaning it has no demonstrable genetic relationship to any other known language family in the world. This makes Zuni particularly fascinating to linguists, as it represents an independent line of linguistic development stretching back millennia. Its unique grammar, vocabulary, and sound system are a testament to its long, isolated history.

4. Hopi Language (Uto-Aztecan Family): Spoken at the Hopi Mesas in northeastern Arizona, Hopi is part of the larger Uto-Aztecan language family, which stretches from the U.S. Southwest down into Mexico. This places Hopi in a linguistic lineage distinct from the New Mexico Pueblos, reflecting a different migratory history and cultural trajectory. Hopi is well-known in linguistic circles for its unique temporal and aspectual system, which some scholars have famously (and sometimes controversially) linked to a different perception of time among its speakers.

Why Such Diversity? A Tapestry Woven Over Millennia

The remarkable linguistic diversity among the Pueblos is a result of several interwoven factors:

- Ancient Migrations and Distinct Origins: The ancestors of today’s Pueblo peoples arrived in the Southwest in different waves, from different directions, and speaking different languages. Some groups may have descended from the ancient Mogollon or Hohokam cultures, while others trace their lineage to the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi).

- Geographical Isolation: For centuries, individual Pueblo communities, though sharing cultural traits, often remained relatively isolated from one another due to geographical barriers like mountains, deserts, and vast distances. This allowed their languages to evolve independently, diverging over time into distinct tongues, much like European languages diverged from a common Indo-European root.

- Cultural Autonomy: Despite shared ceremonial cycles and trade networks, each Pueblo maintained a strong sense of autonomy and distinct identity. Language became a powerful symbol of this distinctiveness, preserving unique histories, spiritual knowledge, and community bonds.

As Dr. Anthony F.C. Wallace, a prominent anthropologist, once noted, "Language is not merely a tool for communication; it is the fundamental medium through which a culture perceives and interprets the world." For the Pueblos, their languages are living archives of their past, repositories of their wisdom, and the very foundation of their sovereignty.

Language as the Heartbeat of Culture

Beyond mere communication, Pueblo languages are deeply intertwined with every aspect of community life. They are the vehicles for:

- Oral Traditions: Histories, myths, songs, and ceremonial knowledge are passed down generation to generation through spoken word. The nuances of pronunciation, rhythm, and tone carry immense cultural weight.

- Spiritual Practices: Many ceremonial songs, prayers, and rituals are conducted entirely in the native language. Some sacred aspects of the language are intentionally guarded and not shared with outsiders, reflecting their profound spiritual significance.

- Connection to Land: Place names, descriptions of natural phenomena, and terms for flora and fauna often embed deep ecological knowledge and a profound spiritual connection to the ancestral lands.

- Social Cohesion: Speaking the language reinforces community bonds, shared values, and a collective identity. It’s a powerful identifier of who belongs and how one relates to the group.

As an elder from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo once expressed, "Our language is like the heart of our people. If the heart stops beating, our people will cease to be who we truly are."

Challenges and the Fight for Revival

Despite their profound cultural importance, Pueblo languages face significant threats. Centuries of external pressures, primarily from Spanish and later American colonial policies, have taken a heavy toll:

- Boarding Schools: From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, a federal policy of forced assimilation sent Native American children to boarding schools, where they were punished for speaking their native languages. This severed the intergenerational transmission of language, creating "silent generations."

- Dominance of English: English became the language of education, commerce, and broader society, leading to a decline in daily use of native languages, particularly among younger generations.

- Intermarriage: As Pueblos increasingly intermarry across different language groups or with non-Native individuals, English often becomes the common language at home.

- Limited Resources: Many Pueblo languages have never been extensively written down or documented, making formal education and preservation efforts challenging, though this is changing.

The numbers are sobering. Many Pueblo languages are now critically endangered, with fluent speakers often limited to the elder generations. According to the Endangered Languages Project, some Pueblo languages have fewer than 100 speakers.

However, a powerful counter-movement is gaining momentum. Pueblo communities are actively engaged in robust, community-led efforts to revitalize and preserve their ancestral tongues:

- Immersion Schools and Classes: Many Pueblos have established their own language programs, from pre-school immersion to adult classes, often taught by elders. These programs aim to create new generations of fluent speakers.

- Documentation and Archiving: Linguists, often working in collaboration with tribal communities, are documenting grammars, creating dictionaries, and archiving oral histories.

- Digital Resources: Apps, online dictionaries, and interactive language lessons are emerging, making learning more accessible, particularly for younger, tech-savvy generations.

- Mentorship Programs: Elders are paired with younger learners, fostering intergenerational knowledge transfer.

- Cultural Integration: Language is being re-integrated into daily life, ceremonies, and tribal government functions, ensuring its relevance beyond the classroom.

For instance, the Tiwa language program at Taos Pueblo is highly regarded, with dedicated teachers working to ensure the language continues to thrive. Similarly, communities like Zuni Pueblo are developing comprehensive language curricula to counter the decline. "It’s a race against time," shared a language teacher from San Ildefonso Pueblo, "but our children are hungry to learn. They understand that without the language, a part of who they are disappears."

A Future Woven in Words

The struggle to preserve Pueblo languages is more than just an academic exercise; it is a fight for cultural survival, identity, and sovereignty. Each word, each phrase, each unique sound system represents a distinct way of knowing and being in the world – a testament to the resilience and adaptability of these ancient peoples.

As visitors and outsiders, we are rarely privy to the full depth and beauty of these languages, especially their sacred aspects. But even a superficial understanding reveals a profound truth: the Pueblo world is not monolithic, but a vibrant, diverse tapestry, each thread woven with the unique sounds and meanings of its own ancestral tongue. These languages are the echoes of millennia, whispering stories of resilience, connection, and an enduring spirit that continues to define the heart of the American Southwest. The hope is that with concerted effort, these echoes will not fade, but will resonate for generations to come, ensuring the heartbeat of Pueblo culture continues to beat strong.