A Grand Bargain, A Broken Promise: The Legacy of the Great Plains Peace Commission

In the tumultuous wake of the American Civil War, as the nation grappled with reconstruction and looked westward with an insatiable hunger for land and resources, a desperate and ambitious plan was conceived. The year was 1867, and the vast expanse of the Great Plains, once an open frontier, had become a cauldron of escalating violence between rapidly expanding American settlers, railroad construction crews, and the Native American nations who had called these lands home for millennia. To quell the bloodshed and secure the path for Manifest Destiny, the United States government established the Great Plains Peace Commission.

Comprising an unlikely mix of battle-hardened Union generals and influential civilian politicians, the Commission was tasked with nothing less than bringing an end to the "Indian Wars" plaguing the frontier. Their mission: to negotiate lasting peace treaties, define reservation boundaries, and usher Native Americans into a new era of sedentary, agricultural life, far from the bison herds and the nomadic existence that defined their cultures. It was a monumental undertaking, born of a mixture of genuine desire for peace, strategic military necessity, and a deeply ingrained belief in American cultural and territorial superiority. Yet, as history would reveal, this grand bargain was fundamentally flawed, its promises ultimately broken, and its legacy one of profound tragedy and betrayal.

The Crucible of Conflict: Why a Commission?

By the mid-1860s, the Great Plains were ablaze. The completion of the transcontinental railroad was deemed a national imperative, but its construction sliced through the heart of Native hunting grounds. Miners, farmers, and cattle ranchers poured into territories that had long been undisturbed, leading to inevitable clashes. The Fetterman Fight in December 1866, where Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors annihilated a U.S. Army detachment near Fort Phil Kearny, sent shockwaves through Washington. It underscored the costly futility of military solutions alone and galvanized support for a diplomatic approach.

As General William Tecumseh Sherman, one of the key military figures on the Commission, famously stated, "We are not going to let a few thieving, untamed savages stop the progress of civilization." This blunt assessment, while revealing the prevailing racist attitudes of the era, also highlighted the government’s dual objective: peace, yes, but peace on terms that facilitated American expansion.

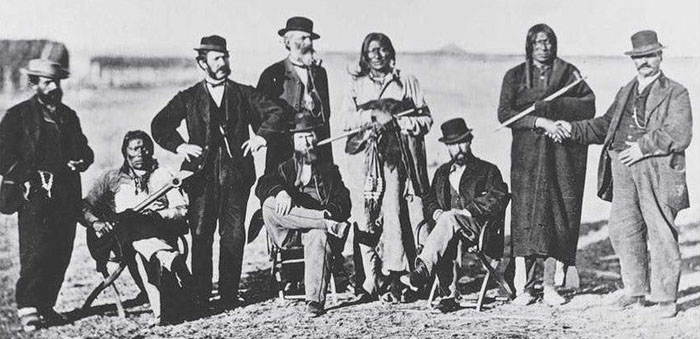

The Commission was formally created by an act of Congress on July 20, 1867. Its members included some of the most prominent figures of the time: Lieutenant General William Tecumseh Sherman, commander of the Military Division of the Missouri; Major General William S. Harney; Major General Alfred H. Terry; Brevet Major General Christopher C. Augur; and civilian commissioners Senator John B. Henderson of Missouri (who sponsored the bill), Nathaniel G. Taylor (Commissioner of Indian Affairs), John B. Sanborn, and Samuel F. Tappan. This mix of military strategists and civilian policymakers reflected the deep divisions within the government itself – whether to pursue a policy of force or conciliation.

The Road to Treaty: Diplomacy Under Duress

The Commission’s journey across the Plains in 1867 and 1868 was an arduous one, covering thousands of miles and confronting immense logistical and cultural challenges. Their primary objective was to meet with representatives of the Southern Plains tribes (Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne, Arapaho) and the Northern Plains tribes (Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, Arapaho).

Their first major council took place in October 1867 at Medicine Lodge Creek in southern Kansas. Here, amidst thousands of tipis and a tense atmosphere, the Commissioners attempted to negotiate with leaders like Satanta (Kiowa), Black Kettle (Cheyenne), and Little Raven (Arapaho). The treaties signed at Medicine Lodge sought to consolidate these tribes onto two reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), promising annuities in goods and services, schools, and agricultural assistance, in exchange for vast tracts of ancestral lands and a pledge to cease hostilities against settlers and the railroads.

A remarkable, if fleeting, moment of cross-cultural understanding occurred during the Medicine Lodge negotiations. Satanta, the Kiowa orator, famously addressed the Commissioners: "I have heard that you intend to settle us on a reservation near the mountains. I don’t want to settle. I love to roam over the prairies. There I feel free and happy, but when we settle down, we grow pale and die." His words were a poignant articulation of the fundamental clash between nomadic lifeways and the American vision of agrarian settlement, a clash the Commission largely failed to grasp or respect.

The following year, the Commissioners turned their attention north, culminating in the monumental Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. This treaty, signed with various bands of the Lakota (Sioux), including Red Cloud, and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies, was perhaps the most significant outcome of the Commission. It established the Great Sioux Reservation, a vast territory encompassing the entire western half of present-day South Dakota, including the sacred Black Hills, and designated additional "unceded Indian territory" for hunting. Crucially, it also guaranteed that no white person would be permitted to settle on or pass through this reservation without the consent of the Lakota, and it abandoned three forts along the Bozeman Trail, a major source of conflict.

Seeds of Failure: The Inherent Flaws

Despite the initial fanfare and the signing of these landmark treaties, the Great Plains Peace Commission was ultimately a failure, and its outcomes laid the groundwork for decades of further conflict. Several fundamental flaws doomed its grand aspirations:

-

Misunderstanding of Tribal Governance: The Commissioners often operated under the mistaken assumption that Native American chiefs held absolute authority similar to European monarchs. In reality, leadership among Plains tribes was decentralized, often based on consensus, and individual bands or even warriors had considerable autonomy. A chief might sign a treaty, but he could not necessarily bind all his people, especially if the terms were unfavorable. Many "signers" were not even recognized as principal chiefs by their people.

-

Broken Promises and Lack of Enforcement: The U.S. government consistently failed to uphold its end of the bargain. Annuities were often late, of poor quality, or stolen by corrupt Indian agents. The promised schools and agricultural aid rarely materialized effectively. Most critically, the government proved unwilling or unable to prevent white encroachment onto treaty lands. The discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874, a clear violation of the Fort Laramie Treaty, ignited the Great Sioux War, proving the treaty’s paper-thin protections.

-

Cultural Chasm: The Commission operated from a perspective of cultural superiority, viewing Native American ways of life as "savage" and in need of "civilizing." They failed to appreciate the deep spiritual and cultural connection Native peoples had to their land, particularly the buffalo, which was being systematically destroyed by hide hunters, further undermining the economic and cultural viability of the reservations.

-

Military Imperatives vs. Peaceful Coexistence: Despite the presence of peace advocates, the underlying military imperative remained. The reservations were not truly sovereign nations but rather territories where tribes were to be contained, their power diminished, and their lands eventually opened for American settlement. As Commissioner Samuel Tappan later reflected, the Commission’s work was "a failure, from the very beginning, in that it was organized by an act of Congress for the sole purpose of getting the Indians onto reservations, without any regard for their future welfare."

The Bitter Harvest: Legacy of Betrayal

The immediate aftermath of the treaties saw a brief, uneasy peace, but it quickly dissolved. The Kiowa and Comanche, finding their reservation lands unsustainable and their promised supplies insufficient, soon resumed raiding. The Cheyenne and Arapaho struggled with the transition, many eventually fleeing the reservation.

For the Lakota, the Fort Laramie Treaty became a symbol of betrayal. While it initially provided some respite, the relentless pressure from settlers and the eventual invasion of the Black Hills for gold led to the ultimate undoing of the peace. The "Red River War" of 1874-75, and the "Great Sioux War" of 1876-77 (which included the Battle of Little Bighorn), were direct consequences of the broken promises and the government’s continued expansionist policies.

The Great Plains Peace Commission, therefore, stands as a poignant historical marker. It was a sincere, if flawed, attempt to resolve a violent conflict through negotiation rather than brute force. Yet, its inherent contradictions – attempting to secure peace while simultaneously dispossessing Native Americans of their ancestral lands and traditional ways of life – rendered it ultimately futile.

The Commission’s report to Congress, while advocating for humane treatment, also recommended the eventual assimilation of Native Americans into American society, laying the groundwork for later policies like the Dawes Act. Its legacy is not one of successful diplomacy, but rather a stark reminder of the power imbalances, cultural misunderstandings, and unfulfilled promises that characterized the United States’ westward expansion and its relationship with Indigenous peoples. The "grand bargain" was, for Native Americans, a broken promise, leading to generations of hardship, loss, and the tragic conclusion of the frontier era.