Here is a 1200-word article in English about the legends of America, focusing on Algonquian peoples, in a journalistic style, including quotes and interesting facts.

The Echoes of Ancient Earth: Unveiling the Legends of Algonquian America

America’s legendary landscape is often painted with the broad strokes of European folklore – Paul Bunyan’s colossal logging feats, Johnny Appleseed’s verdant trails, or Rip Van Winkle’s enchanted slumber. Yet, beneath this familiar surface lies an infinitely older, deeper wellspring of narrative: the vibrant, profound, and often misunderstood legends of the continent’s Indigenous peoples. Among these, the traditions of the Algonquian-speaking nations stand as a monumental testament to human imagination, spiritual connection, and the enduring power of storytelling.

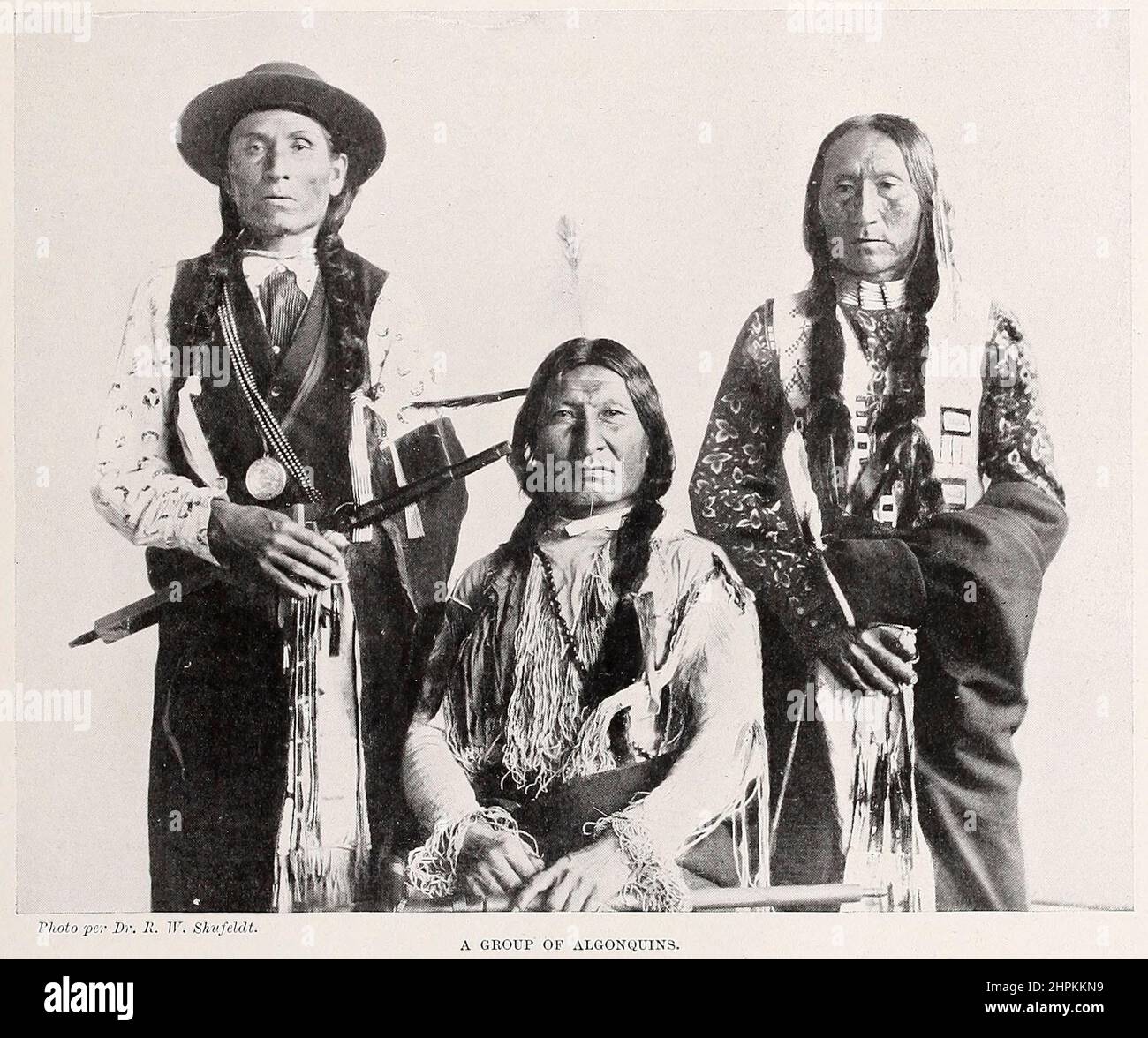

Stretching from the Atlantic coast across the Great Lakes and into the vast plains, the Algonquian language family once united a diverse array of peoples, including the Lenape, Wampanoag, Narragansett, Ojibwe (Anishinaabe), Cree, Powhatan, Shawnee, and many more. Despite their distinct cultures and geographical separation, these nations shared a common linguistic root and, often, overlapping themes in their rich oral traditions. Their legends are not mere fairy tales; they are intricate tapestries woven from history, prophecy, moral instruction, spiritual guidance, and scientific observation, passed down through generations long before the arrival of European chroniclers.

The Oral Archives: A Living Legacy

For millennia, the primary mode of knowledge transmission among Algonquian peoples was the spoken word. Elders, storytellers, and ceremonial leaders were the living libraries, entrusted with the sacred duty of preserving and relaying these narratives. "Our stories are our history, our law, our philosophy, our very being," is a sentiment echoed by countless Indigenous knowledge keepers. This oral tradition ensured that the legends remained fluid, adapting to new circumstances while retaining their core truths, reflecting the dynamic relationship between people, land, and spirit.

These stories often unfold in a cyclical understanding of time, where the past is always present, shaping the future. They offer explanations for natural phenomena – why the raven is black, how the mountains were formed, or why certain plants hold healing properties. More profoundly, they outline ethical frameworks, define social roles, and connect individuals to a vast, intricate web of relations encompassing all living things and the spiritual realm.

The Trickster’s Teachings: Nanabozho and Glooscap

Central to many Algonquian legend cycles is the figure of the Trickster. Far from a simple villain or mischievous sprite, the Trickster is a complex, multifaceted being who embodies both creation and destruction, wisdom and folly, generosity and greed. For the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi), this figure is often Nanabozho (also known as Wenabozho or Manabozho). For the Wabanaki Confederacy (Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, Abenaki, Mi’kmaq), it is Glooscap (Klooskap). The Cree and Algonquin peoples often speak of Wisakedjak (Weesageechak).

These Tricksters are culture heroes, shapeshifters capable of transforming into animals, plants, or even natural elements. They are responsible for shaping the world, often inadvertently, through their adventures. Nanabozho, for instance, is credited with creating the world after a great flood, using a piece of earth brought up by a muskrat or beaver. He taught his people how to hunt, fish, and gather, and how to understand the cycles of nature.

Yet, Tricksters are also deeply flawed. They are impulsive, gluttonous, boastful, and sometimes cruel. Their misadventures often serve as cautionary tales, demonstrating the consequences of arrogance or disrespect. "The Trickster reminds us that life is messy, that perfection is an illusion, and that even our mistakes can lead to profound lessons," explains Dr. Lisa Brooks (Abenaki), a scholar of Indigenous literature. This duality makes the Trickster a profoundly human and relatable figure, reflecting the complexities and contradictions inherent in human nature itself.

Creation and the Earth-Diver Myth

Many Algonquian nations share variations of the "Earth-Diver" creation myth, a powerful narrative explaining the origin of the land. In these stories, the world is initially covered by a vast expanse of water. A benevolent creator figure (sometimes Nanabozho, sometimes a more abstract Great Spirit) sends various animals – often a muskrat, beaver, or loon – to dive to the bottom to retrieve a piece of earth. After many failed attempts, one small, persistent animal succeeds, bringing up a tiny bit of mud. This small piece of earth is then placed on the back of a giant turtle, or grows miraculously, expanding to form the entire continent, which is why North America is sometimes referred to as "Turtle Island."

This creation story profoundly shapes the Algonquian relationship with the land. It instills a deep sense of reverence for the earth as a living entity, a gift born from collective effort and sacrifice. The interconnectedness of all beings – human, animal, and spiritual – is central to this worldview, fostering a sense of responsibility for stewardship rather than dominion.

Animal Spirits and the Web of Life

Animals are not merely characters in Algonquian legends; they are often teachers, guides, and spiritual kin. The bear, for example, is revered for its strength, healing powers, and the ability to hibernate and re-emerge, symbolizing renewal. The wolf represents loyalty, family, and wisdom. The eagle is a messenger to the Creator, embodying courage and spiritual insight.

These animal stories teach children and adults alike about the unique qualities of each creature, their roles in the ecosystem, and the lessons they offer for human behavior. They reinforce the idea that humans are not superior to other species but are part of a shared existence, each with their own gifts and responsibilities. Learning about the characteristics of the animals in the stories provided practical knowledge for hunting, tracking, and understanding the natural world, blurring the lines between myth and empirical observation.

Heroes, Warnings, and Misinterpretations

Beyond creation and trickster tales, Algonquian legends include narratives of great heroes who brought vital knowledge or technologies, and cautionary tales that warn against social transgressions like greed, envy, or disrespect for elders. These stories served as a powerful form of social control and moral education, ensuring community cohesion and the transmission of cultural values.

However, the encounter with European cultures often led to profound misunderstandings and misrepresentations of these legends. Perhaps the most famous example is Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, "The Song of Hiawatha." While widely popular, Longfellow’s poem mistakenly attributes the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) culture hero Hiawatha to an Algonquian context, weaving a romanticized and largely inaccurate narrative. The true Hiawatha, a historical figure, worked with the Great Peacemaker to unite the warring nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, establishing a sophisticated democratic system centuries before the American Constitution. This illustrates the danger of outsiders appropriating and distorting Indigenous narratives, stripping them of their original meaning and cultural specificity.

The Enduring Power and Resurgence

The arrival of European colonizers brought immense pressure to bear on Algonquian oral traditions. Forced assimilation policies, residential schools, and the suppression of Indigenous languages threatened to silence these ancient voices. Many stories were lost, or driven underground. Yet, remarkably, countless legends persisted, whispered in secret, remembered in ceremony, and carried in the hearts of knowledge keepers.

Today, there is a powerful resurgence of interest and dedication to revitalizing Algonquian legends. Communities are actively engaged in language immersion programs, cultural workshops, and the creation of new media – books, films, and digital archives – to ensure these stories are passed on to future generations. Scholars like Dr. Brooks emphasize the critical role of these narratives: "These legends are not relics of the past; they are living, breathing guides for navigating the present and imagining a just future. They offer alternative models of governance, environmental stewardship, and human relationships that are desperately needed today."

The legends of the Algonquian peoples offer a profound counter-narrative to the dominant American story. They remind us that this land has always been alive with meaning, imbued with the wisdom of its original inhabitants. To truly understand America, one must listen to the ancient echoes of its first storytellers, whose voices continue to resonate through the forests, along the rivers, and across the vast landscapes of Turtle Island, inviting us to learn, respect, and reconnect with the Earth in a more profound way. Their legends are not just American legends; they are universal truths, waiting to be heard.