America’s Dark Canvas: The Enduring Enigma of Serial Killers

Few phenomena grip the American psyche with such a chilling blend of horror and morbid fascination as serial killers. From the shadowy figures haunting remote landscapes to the seemingly ordinary neighbors concealing monstrous secrets, these individuals have carved a unique, terrifying niche in the nation’s cultural narrative. They represent the ultimate betrayal of trust, the shattering of societal norms, and a stark reminder of the darkness that can lurk within the human heart. But why has America, in particular, seemed to produce and contend with such a disproportionate number of these predators? The answer lies in a complex interplay of geography, societal shifts, law enforcement evolution, and the very fabric of American liberty.

The term "serial killer" itself, popularized by FBI agent Robert Ressler in the 1970s, describes an individual who commits a series of murders over a period of time, typically with a "cooling-off" period between killings, and driven by psychological compulsion rather than financial gain or political ideology. While isolated cases of multiple murderers have existed throughout history, the latter half of the 20th century saw the phenomenon explode into public consciousness, forever altering the landscape of American crime.

The Golden Age of Terror: The 1970s and 80s

The decades of the 1970s and 1980s are often referred to as the "golden age" of serial killing in America. This period saw an unprecedented surge in identified cases, with estimates suggesting hundreds of active serial killers during this time. Several factors converged to create this grim environment. The rise of the interstate highway system facilitated unprecedented mobility, allowing killers to cross state lines, evade local authorities, and expand their hunting grounds. Urbanization and the increasing anonymity of city life provided cover, making it easier for predators to blend in and disappear. Furthermore, forensic science was still in its relative infancy, and inter-agency communication between law enforcement bodies was often fragmented and inefficient.

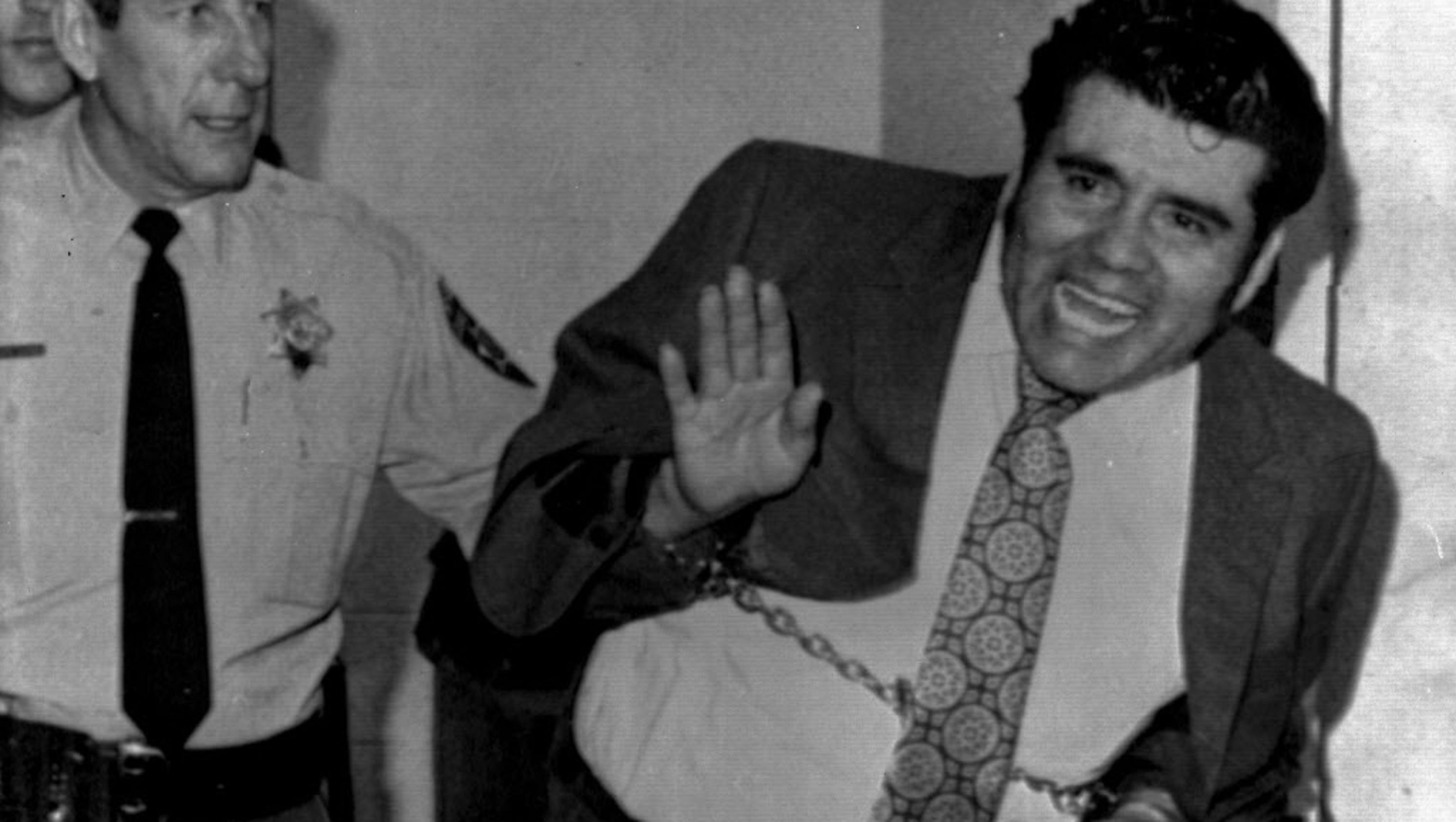

It was during this era that some of America’s most infamous serial killers operated, their names becoming synonymous with terror. Ted Bundy, the charming, articulate law student who confessed to over 30 murders across several states, epitomized the "wolf in sheep’s clothing." His ability to appear utterly normal, even charismatic, shattered public perceptions of what a murderer looked like. John Wayne Gacy, the beloved local clown and community figure, hid the bodies of 33 young men beneath his suburban Chicago home, a stark reminder that evil could reside next door. Jeffrey Dahmer, the Milwaukee cannibal, committed acts of unimaginable depravity that pushed the boundaries of human comprehension. These cases, widely publicized, amplified public fear and fascination, forcing a national reckoning with the existence of such monsters.

The Psychology of the Predator: Nature vs. Nurture

Understanding why serial killers commit their heinous acts is a perpetual quest for psychologists, criminologists, and law enforcement. While no single profile fits all, common threads often emerge. Most researchers agree on a complex interaction of genetic predispositions, early childhood trauma, and environmental factors. Many serial killers report histories of severe abuse, neglect, or profound social isolation during their formative years. For some, a combination of head injuries, neurological disorders, and personality disorders like psychopathy or antisocial personality disorder can contribute to a lack of empathy, impulsivity, and a disregard for social norms.

FBI profilers, particularly those from the Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU) at Quantico, pioneered the study of serial killer motivations and methodologies. Agents like John E. Douglas and Robert Ressler, who interviewed numerous incarcerated serial killers, developed typologies that helped law enforcement understand patterns. They identified categories such as "organized" killers (meticulous, intelligent, often charming, like Bundy) and "disorganized" killers (impulsive, less sophisticated, often socially awkward, like Dahmer). They also delved into the various motivations:

- Visionary: Driven by voices or visions (e.g., Herbert Mullin).

- Missionary: Believe they are ridding the world of a certain type of person (e.g., prostitutes or a specific racial group).

- Hedonistic: Kill for pleasure, either from the act itself (lust killers), the thrill, or for comfort/gain.

- Power/Control: The primary motivation is the complete domination and control over their victims (e.g., Dennis Rader, BTK).

"The motives are as varied as the individuals themselves," noted John E. Douglas in his book Mindhunter. "But a common thread is almost always a profound sense of inadequacy, a need for power, and a complete lack of empathy for their victims." This chilling detachment allows them to objectify and dehumanize their targets, transforming them from living beings into instruments of their dark fantasies.

Law Enforcement’s Evolving Response: From Instinct to Science

The escalating crisis of serial killings spurred significant advancements in law enforcement. The FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit became a crucial resource, providing psychological profiles based on crime scene analysis to help local police narrow down suspect pools. The establishment of VICAP (Violent Criminal Apprehension Program) in 1985 was a landmark step, creating a national database for law enforcement agencies to share information on unsolved homicides, enabling the identification of cross-jurisdictional patterns that might indicate a serial offender.

However, it was the advent of DNA profiling in the late 1980s and early 1990s that revolutionized cold case investigations and apprehension rates. DNA evidence, often found in minuscule quantities at crime scenes, provided an irrefutable link between perpetrator and victim, leading to the identification and conviction of many previously elusive killers. The Green River Killer, Gary Ridgway, responsible for dozens of murders in Washington State, was finally apprehended in 2001 after two decades, thanks to DNA technology linking him to earlier victims. More recently, advancements in forensic genealogy have allowed investigators to use public DNA databases to identify suspects through distant relatives, leading to arrests in long-cold cases like the Golden State Killer, Joseph DeAngelo, who terrorized California for decades.

These technological leaps, combined with improved inter-agency cooperation and heightened public awareness, have contributed to a significant decline in the number of active serial killers since the peak in the 1980s. While they certainly still exist, their "careers" are often shorter, and their chances of evading capture indefinitely have diminished considerably.

The Media, True Crime, and Public Fascination

The media has played a dual role in the narrative of serial killers. On one hand, extensive coverage has undoubtedly contributed to public fear, sometimes bordering on sensationalism. The term "serial killer" itself became a pop culture phenomenon, spawning countless films, books, and television shows. The Silence of the Lambs, with its iconic character Hannibal Lecter, cemented the public’s morbid fascination with the criminal mind.

On the other hand, media coverage has also served a vital public service, raising awareness, disseminating information, and keeping the pressure on law enforcement. The true crime genre, in particular, has exploded in popularity, from podcasts to documentaries, allowing the public to delve into the intricacies of these cases. This fascination often stems from a primal desire to understand the incomprehensible, to seek patterns in chaos, and perhaps, to feel a sense of control by dissecting the very things that threaten our safety. Yet, critics argue that this fascination can inadvertently glorify the killers, turning them into dark celebrities rather than focusing on the victims and their profound loss.

The Victims and Lingering Shadows

Often lost in the sensationalism surrounding the killers themselves are the victims. They are not merely statistics or plot devices; they are individuals with lives, families, and futures brutally stolen. The impact on their loved ones is immeasurable and enduring. Families are left grappling not only with grief but often with unanswered questions, public scrutiny, and the agonizing wait for justice. For communities, the presence of a serial killer instills a pervasive fear, eroding trust and altering daily life.

Despite the decline in numbers, the shadow of the serial killer continues to loom large in the American consciousness. They remain a chilling reminder of the fragility of life and the capacity for extreme evil. While law enforcement has become more adept at identifying and apprehending these individuals, the fundamental questions persist: What combination of factors creates such a predator? Can they ever truly be "cured"? And how can society better identify and intervene with individuals on a path toward such depravity?

America’s vastness, its emphasis on individual liberty (which can sometimes translate to anonymity), and its unique cultural landscape have all contributed to making it a complex stage for the phenomenon of serial killing. The ongoing study of these dark chapters continues to shape criminal justice, forensic science, and our understanding of the deepest, most disturbing aspects of human behavior. The goal is not just to catch those who commit these unspeakable acts, but to understand the darkness, to mitigate its causes, and ultimately, to protect the innocent from its chilling embrace.