Audie Murphy: The Boy Hero, The Reluctant Star, and the Enduring Cost of War

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

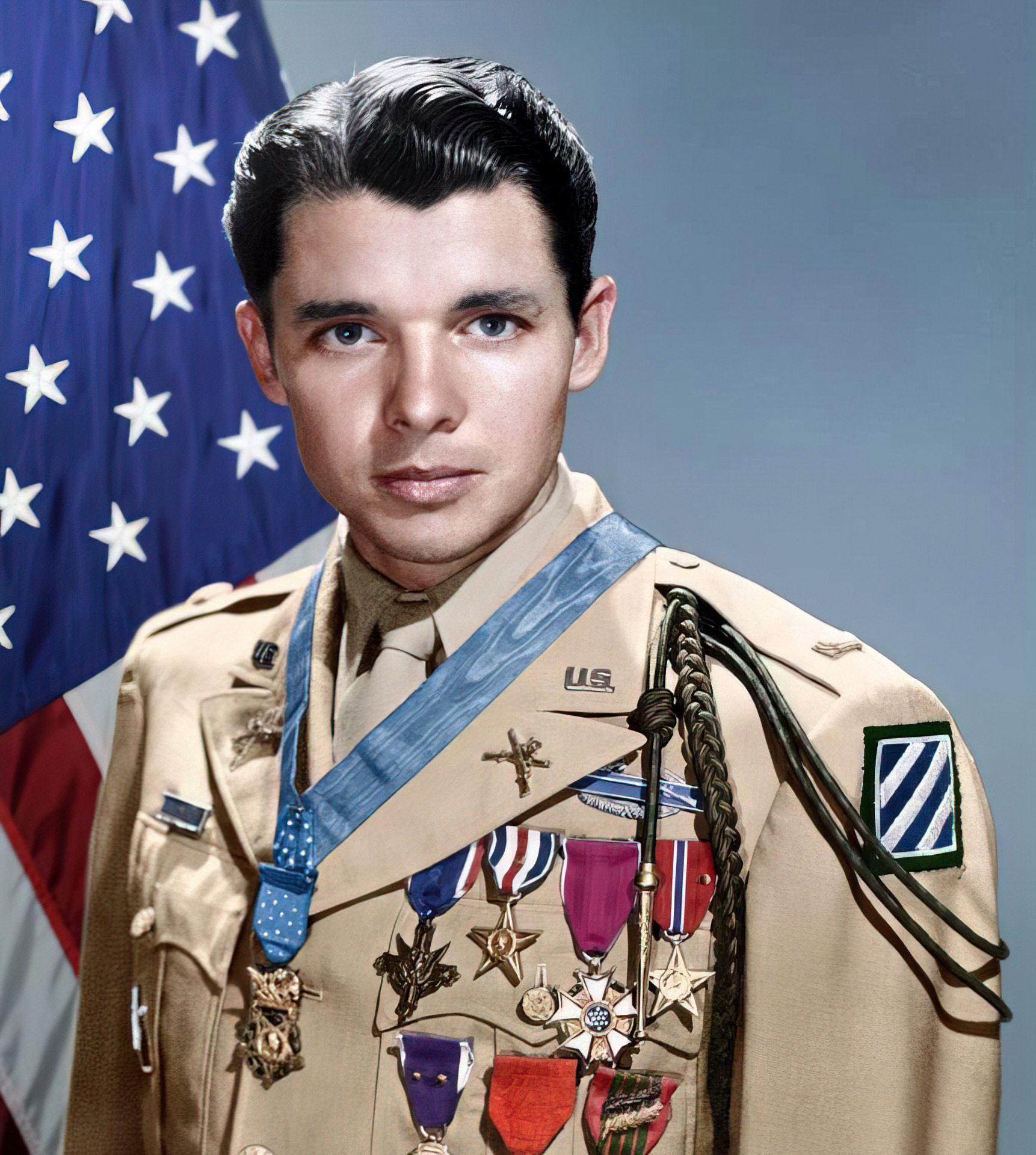

The image is etched into the American consciousness: a slight, unassuming young man, barely out of his teens, yet adorned with more medals for valor than any other soldier in U.S. history. Audie Leon Murphy, a name synonymous with unparalleled bravery, a legend forged in the crucible of World War II. But beneath the hero’s mantle lay a complex, tormented soul, a man who battled not only the enemy on the front lines but also the demons that followed him home, long after the last shot was fired. His story is a quintessential American epic, a testament to courage, resilience, and the often-overlooked, profound cost of war.

Born into abject poverty in Kingston, Texas, in 1925, Audie Murphy’s early life was a relentless struggle for survival. The son of a sharecropper, he was one of twelve children, many of whom did not survive infancy. His father abandoned the family when Audie was young, leaving his mother to raise the remaining nine children in squalor. Murphy often recounted hunting small game to put food on the table, a skill that would later serve him in a far deadlier arena. He dropped out of fifth grade to work in cotton fields and sawmills, his childhood stolen by necessity. This harsh upbringing instilled in him a fierce independence and an unyielding will to protect those he loved – qualities that would soon manifest on a global stage.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Murphy, barely 16, was eager to enlist. His motives were not solely patriotic; he saw the military as an escape from poverty and a way to provide for his younger sister. He tried to join the Marines, then the paratroopers, but was rejected by both for being too small and underweight, standing just 5 feet 5 inches and weighing 110 pounds. Undeterred, he falsified his birth certificate, claiming to be 18, and was finally accepted into the U.S. Army in June 1942. It was a decision that would transform him from an anonymous farm boy into America’s most decorated soldier.

Murphy’s journey began in North Africa in 1943, though his unit, the 3rd Infantry Division, didn’t see combat there. His baptism by fire came during the Allied invasion of Sicily, followed by the brutal fighting in Italy, particularly at Anzio and the Volturno Line. From the outset, Murphy displayed an uncanny coolness under fire, a natural aptitude for combat that belied his youthful appearance. He quickly rose through the ranks, from private to staff sergeant, earning a reputation for exceptional bravery and leadership.

His legend truly began to solidify during the relentless campaigns through France. In August 1944, during the fighting near Ramatuelle, Murphy’s best friend, Lattie Tipton, was killed by a German machine gunner while feigning surrender. Enraged, Murphy single-handedly charged the enemy position, killing the entire crew and then turning their own machine gun on other Germans, killing two more and wounding several. This act earned him the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest military decoration.

But it was in January 1945, in the midst of the brutal winter fighting in the Colmar Pocket in France, that Audie Murphy performed the actions that would earn him the Medal of Honor. His company, part of the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, was holding a position near Holtzwihr when they were attacked by six German tanks and waves of infantry. Murphy, by then a first lieutenant and company commander, ordered his men to retreat into the woods while he remained behind, directing artillery fire. As the Germans pressed forward, an American M10 tank destroyer was hit and set ablaze, threatening to explode. Murphy, ignoring his own safety and suffering from a leg wound, climbed onto the burning tank destroyer.

From this exposed, incredibly vulnerable position, with explosions rocking the vehicle beneath him, he manned its .50 caliber machine gun. For an hour, he unleashed a devastating barrage on the advancing German infantry, holding them at bay and calling in artillery fire dangerously close to his own position. He single-handedly repelled the attack, killing an estimated 50 Germans and wounding many more. When he finally ran out of ammunition, he calmly walked back to his company, refusing medical attention until he was certain the enemy threat had subsided. His official Medal of Honor citation reads: "Lt. Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction, and enabled it to hold a critical sector of the front."

By the time the war in Europe ended, Audie Murphy had accumulated an astonishing 33 awards and decorations, including the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, the Legion of Merit, and two Bronze Stars. He was also awarded the French Croix de Guerre with Palm, the French Legion of Honor, and the Belgian Croix de Guerre. He had personally killed over 240 enemy soldiers, wounded countless more, and captured a significant number. He was, without question, the most decorated American soldier of World War II.

When he returned home in 1945, Murphy was thrust into the spotlight as a national hero. Life magazine featured him on its cover, and he was met with ticker-tape parades and adulation. But the transition from battlefield to civilian life was anything but smooth. The quiet, intense young man found himself a celebrity, a symbol of American courage, yet profoundly ill-equipped for the demands of fame. The horrors he had witnessed and perpetrated had left indelible scars. He suffered from what was then called "shell shock" or "combat fatigue," now known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

He battled severe insomnia, nightmares, and chronic depression. He confessed to sleeping with a loaded pistol under his pillow and admitted to struggling with a "temper that flares out of control." He famously stated, "I don’t think I’ve had a night’s sleep in twenty years without waking up and seeing the faces of dead men." He became addicted to sleeping pills, a struggle he bravely confronted and overcame, later advocating for other veterans dealing with similar issues. Murphy was one of the first public figures to openly discuss the psychological wounds of war, long before it became a recognized medical condition, offering solace and understanding to countless veterans who suffered in silence.

His fame, however, opened an unexpected door: Hollywood. Actor James Cagney, impressed by Murphy’s Life magazine cover, invited him to Hollywood. Despite having no acting experience, Murphy was signed to a contract. His film career spanned two decades, with him starring in 44 films, predominantly Westerns. His most iconic role was playing himself in the 1955 film adaptation of his best-selling autobiography, "To Hell and Back." The movie was a massive commercial success, becoming Universal Pictures’ biggest hit until "Jaws" two decades later. It was a surreal experience for Murphy, reliving his most traumatic moments for the cameras. He was a natural fit for the stoic, laconic cowboy roles, embodying the strong, silent hero that Americans admired.

Yet, even in Hollywood, the war cast a long shadow. Murphy found it difficult to escape his hero persona, often typecast in roles that echoed his military image. While financially successful for a time, his personal life remained tumultuous. He married twice and faced various financial troubles, including gambling losses and bad investments. The demons of war continued to haunt him, affecting his relationships and overall well-being. He was a complex figure, fiercely loyal to his friends, generous to a fault, yet capable of sudden, unpredictable outbursts.

In the late 1960s, Murphy’s financial situation deteriorated, exacerbated by the changing landscape of Hollywood and his own struggles. He continued to advocate for veterans, particularly those returning from Vietnam, emphasizing the need for mental health support. He understood, perhaps better than anyone, the invisible wounds that often outlast the physical ones.

On May 28, 1971, Audie Murphy’s life came to a tragic end. He was killed in a plane crash in Virginia while on a business trip. He was just 45 years old. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, his grave becoming one of the most visited sites in the cemetery, second only to that of President John F. Kennedy. His simple white headstone, unlike those of other Medal of Honor recipients, does not bear gold leaf, a request he made himself, perhaps a final testament to his humility despite his extraordinary achievements.

Audie Murphy’s legacy is multifaceted. He remains an enduring symbol of American courage and heroism, a small man who faced overwhelming odds and emerged victorious. His story is taught in schools and remembered in military academies as the epitome of a soldier’s valor. But his life also serves as a poignant reminder of the profound and lasting impact of war, not just on the battlefield, but on the human spirit. He was a man who brought the fight home, a testament to the fact that while the parades may end and the medals may be put away, the internal battles often continue long after the guns fall silent. Audie Murphy was not just a hero; he was a human being who exemplified both the glory and the devastating cost of defending freedom. His life continues to resonate, reminding us to honor not only the bravery of our service members but also to acknowledge and support their struggles long after their service has concluded.