Beyond the Gold Pan: The Unsung Architects of Fortune in the Klondike Gold Rush

The enduring image of the Klondike Gold Rush, forever etched in the annals of history, is one of rugged men: pickaxes slung over shoulders, faces hardened by the Yukon wind, eyes gleaming with the feverish hope of striking it rich. They are the stampeders, the prospectors, the solitary figures battling the elements on the Chilkoot Pass, driven by the siren call of gold. Yet, behind, beside, and often demonstrably ahead of these men, was a diverse and formidable cohort whose stories have too often been relegated to the footnotes: the women of the Klondike. Far from mere camp followers, these women were entrepreneurs, adventurers, laborers, and visionaries, who not only survived the brutal frontier but actively shaped its very fabric, striking gold in more ways than one.

The Klondike Gold Rush, ignited by the discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek in August 1896, unleashed a torrent of humanity toward the remote Yukon Territory. News of the strike, initially met with skepticism, exploded across the world in July 1897 when the first gold-laden ships arrived in San Francisco and Seattle. Suddenly, tens of thousands – an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 – abandoned their lives to chase the dream of instant wealth. While the vast majority were men, a significant percentage, perhaps 10-20%, were women, embarking on a journey fraught with peril and defying the staid expectations of Victorian society.

The journey itself was a crucible that melted away societal expectations. To reach the goldfields, stampeders had to traverse treacherous mountain passes like the Chilkoot or White Pass, carrying a year’s worth of supplies – an estimated one ton – mandated by the Canadian government to prevent starvation. This meant repeated trips, hauling packs weighing up to 100 pounds, often in sub-zero temperatures, through blizzards and over icy terrain. For women, this ordeal was no less demanding. Accounts from the trail speak of women, sometimes in long skirts, sometimes in daring new "bloomers," shouldering their burdens alongside men, their determination as unyielding as the permafrost beneath their feet.

One such account comes from Martha Black, who would later become the second woman elected to the Canadian House of Commons. She recalled the trail, "Every step was an effort, but I was going to the Klondike, and nothing could stop me." Her resilience, and that of countless others, demonstrated that the frontier cared little for gender; survival was the only currency. These women weren’t just enduring; they were actively participating in the most arduous part of the journey, proving their mettle before even reaching the goldfields.

Upon arrival in burgeoning boomtowns like Dawson City, a raw, chaotic settlement that sprang up at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon Rivers, the true entrepreneurial spirit of women came to the fore. While a few women did stake claims and prospect – like Kate Carmack, a Tagish First Nation woman whose brother, Skookum Jim, and husband, George Carmack, were credited with the initial discovery – the vast majority understood that the surer path to fortune lay not in the fickle ground, but in providing services to the overwhelmingly male population.

Dawson City, with its population swelling from a handful to over 30,000 in just a few years, was a place where basic necessities were luxuries, and services commanded exorbitant prices. This environment was ripe for female ingenuity. Laundresses, for example, could earn a fortune. Men, working long hours in the muck, were desperate for clean clothes, and a single shirt could cost as much as $5 (equivalent to over $150 today). As Belinda Mulrooney, perhaps the most famous female entrepreneur of the Klondike, succinctly put it, "I made my fortune not by finding gold, but by washing the shirts of those who did."

Mulrooney, an Irish immigrant with a sharp mind for business, arrived in the Klondike with little more than $5,000 and an iron will. She quickly identified needs: first by selling food, then building a roadhouse, and eventually constructing Dawson’s most luxurious hotel, the Fairview. She invested in mines, a sawmill, and real estate, accumulating a vast fortune that cemented her legacy as the "richest woman in the Klondike." Her story is a testament to the fact that in the lawless, opportunity-rich frontier, conventional gender roles could be cast aside for those with the courage and vision to seize their chance.

Beyond laundresses and hoteliers, women ran restaurants, boarding houses, and bakeries. A hot meal was liquid gold, and a comfortable bed a precious commodity. Many a man, weary from the diggings, gladly paid handsomely for a home-cooked meal and a clean cot. Nellie Cashman, known as "The Miner’s Angel," was another extraordinary figure. Having previously worked in various gold rushes across the American West, Cashman arrived in the Klondike in 1898. She opened restaurants, invested in mines, and tirelessly nursed the sick, often without pay, earning a reputation for both shrewd business sense and boundless compassion. She was known to walk hundreds of miles through blizzards to deliver supplies or aid stranded miners.

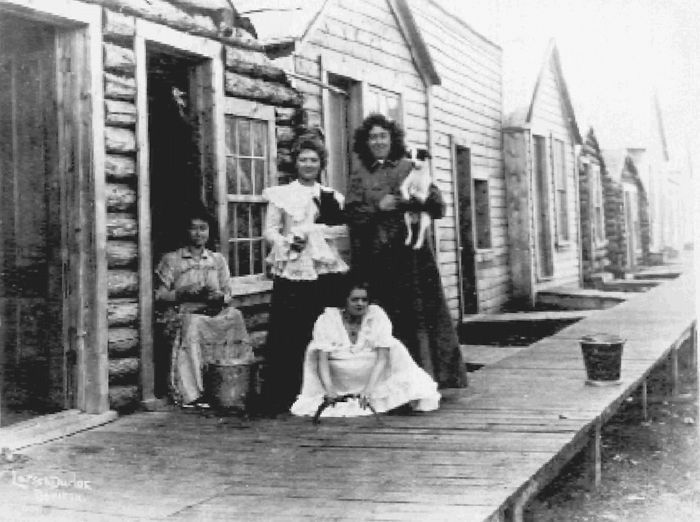

The entertainment industry also thrived, offering women another avenue for economic independence, albeit one often fraught with social stigma. Dance hall girls, singers, and saloon owners became fixtures of Dawson’s nightlife. While some were indeed prostitutes, others used their positions to accumulate wealth and influence. "Klondike Kate" Rockwell, a celebrated dance hall performer, captivated audiences with her beauty and stage presence. Though her legend often overshadows her shrewd financial dealings, Kate was a savvy investor in mining claims and real estate, using her earnings to build a comfortable life. These women, whether performing on stage or behind a bar, provided a vital service – distraction, companionship, and a semblance of social life – in a lonely, male-dominated world.

For some women, the Klondike represented an escape from restrictive societal norms, offering an unprecedented degree of freedom and autonomy. In a frontier town, where the rules of civilization were still being written, a woman could reinvent herself, pursue unconventional careers, and achieve financial independence in ways that would have been impossible in established cities. The sheer distance and isolation of the Klondike created a unique social dynamic where individual initiative often outweighed social standing or gender.

However, this newfound freedom was not without its challenges. Women faced harsh living conditions, the constant threat of disease, and the pervasive moral judgment of a society still grappling with their presence in such a wild environment. Stereotypes abounded, and women were often categorized as either virtuous "respectable" wives and mothers or "fallen" women of questionable character. Yet, the reality was far more nuanced, with many women blurring these lines, navigating their circumstances with pragmatism and resilience.

The presence of women also had a profound "civilizing" effect on the rough-and-tumble boomtowns. Their desire for comfort, community, and domesticity spurred the development of more permanent structures, schools, churches, and social organizations. They brought a sense of order and stability to what might otherwise have remained purely transient mining camps. As historian Mary Lee Stearns noted, "The women’s presence brought a measure of domesticity and culture, helping to transform a raw frontier outpost into a viable community."

By the turn of the century, as the easily accessible gold began to dwindle and large corporations moved in with dredging equipment, the Klondike Gold Rush began to wane. But the legacy of its women endured. They proved that courage, tenacity, and entrepreneurial spirit were not exclusive to one gender. They demonstrated that economic opportunity could transcend societal barriers, and that the frontier, despite its hardships, could be a place of liberation and self-discovery.

The stories of the Klondike women force us to re-examine the historical narrative of the gold rush, moving beyond the romanticized image of the lone male prospector to appreciate the complex tapestry of human experience that defined this extraordinary period. From the arduous journey over the passes to the bustling streets of Dawson City, women were not merely witnesses to history; they were active participants, shaping its course and laying foundations for future generations. Their "gold" was often not found in the earth, but forged through sheer will, ingenuity, and an unwavering belief in their own capabilities, proving that in the Klondike, fortunes were struck in more ways than one, often by hands less expected. Their stories remind us that true history is always richer, more diverse, and infinitely more compelling than the simplified narratives we often inherit.