Beyond the Silence: The Resurgence of Native American Voices in Literature and Media

For centuries, the American literary and artistic landscape was a vast, largely silent prairie for the continent’s Indigenous peoples. Their stories, rich with history, culture, and profound spiritual connection to the land, were either relegated to anthropological studies, distorted through the lens of non-Native authors, or simply ignored. "NA writing credits"—understood here as Native American writing credits—were historically a rarity, a testament to systemic erasure and marginalization. Yet, in an increasingly interconnected world, a powerful shift is underway. Indigenous authors, screenwriters, poets, and playwrights are not just finding their voices; they are reclaiming narratives, challenging stereotypes, and weaving a vibrant, complex tapestry that is finally receiving the recognition it profoundly deserves. This burgeoning resurgence is not merely about representation; it is about sovereignty, cultural preservation, and the vital contribution of Indigenous perspectives to the global human story.

The journey from silence to prominence has been arduous, marked by generations of struggle against colonial oppression, forced assimilation, and the persistent "vanishing Indian" trope that sought to relegate Native peoples to the past. Before the written word, Indigenous cultures thrived on sophisticated oral traditions—epics, histories, songs, and teachings passed down through generations. These were living libraries, intricate and profound, shaping societies and worldview. However, with European contact and subsequent colonization, these traditions were devalued, suppressed, and often deliberately destroyed.

Early non-Native literature often depicted Indigenous peoples in simplistic, often dehumanizing ways: as "noble savages," bloodthirsty warriors, or tragic figures doomed to extinction. These portrayals, from James Fenimore Cooper to Karl May, cemented harmful stereotypes that permeated the popular imagination for centuries. They stripped Indigenous peoples of their individuality, their complex societies, and their inherent humanity, making it difficult for authentic Native voices to emerge and be taken seriously within the dominant publishing structures. The gatekeepers of literature and media were overwhelmingly non-Native, and their understanding of Indigenous experiences was, at best, limited and, at worst, deeply prejudiced.

Despite these immense barriers, a few courageous voices managed to break through in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Authors like Zitkála-Šá (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, Yankton Dakota) offered poignant autobiographical accounts that exposed the brutal realities of boarding schools and the struggle to navigate two worlds. Later, D’Arcy McNickle (Salish Kootenai) and Mourning Dove (Christine Quintasket, Sinixt) laid further groundwork, their works often serving as crucial, if sometimes overlooked, bridges between oral tradition and the written novel. However, it wasn’t until N. Scott Momaday’s 1969 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for House Made of Dawn that a Native American writer achieved widespread critical acclaim within the mainstream literary establishment. Momaday’s victory was a watershed moment, signaling the potential for Indigenous narratives to transcend niche categories and speak to universal human experiences.

The late 20th century saw a slow but steady increase in Native American literary output. The Native American Renaissance, as it came to be known, brought forth formidable talents like Louise Erdrich (Ojibwe), whose rich, multi-generational sagas like Love Medicine and The Round House have garnered numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize. Leslie Marmon Silko (Laguna Pueblo) gave us Ceremony, a seminal work that explored the trauma of war and the healing power of cultural tradition. Sherman Alexie (Spokane/Coeur d’Alene), despite later controversies, was instrumental in bringing contemporary Native humor and angst to a wide audience with works like The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven and the screenplay for Smoke Signals, which became a landmark film. These authors not only expanded the literary canon but also provided crucial visibility and validation for Native communities.

Today, the landscape of Native American writing credits is more vibrant and diverse than ever before. Joy Harjo (Muscogee Nation), a master poet whose work resonates with deep spiritual wisdom and fierce resilience, served an unprecedented three terms as the U.S. Poet Laureate, bringing Indigenous poetry to national prominence. Her tenure was a powerful symbol of the nation finally acknowledging the profound artistic contributions of its first peoples.

Beyond poetry, contemporary Native writers are excelling in every genre imaginable. Tommy Orange (Cheyenne and Arapaho) captivated readers with There There, a powerful, polyphonic novel exploring the complexities of urban Native identity, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Stephen Graham Jones (Blackfeet), a prolific and acclaimed author, has redefined horror literature with chilling and insightful works like The Only Good Indians and My Heart is a Chainsaw, proving that Native stories are not confined to historical fiction or cultural studies, but can brilliantly infuse and innovate mainstream genres. Rebecca Roanhorse (Ohkay Owingeh/African American) has made significant waves in science fiction and fantasy, building intricate worlds steeped in Indigenous cosmologies and challenging conventional genre tropes.

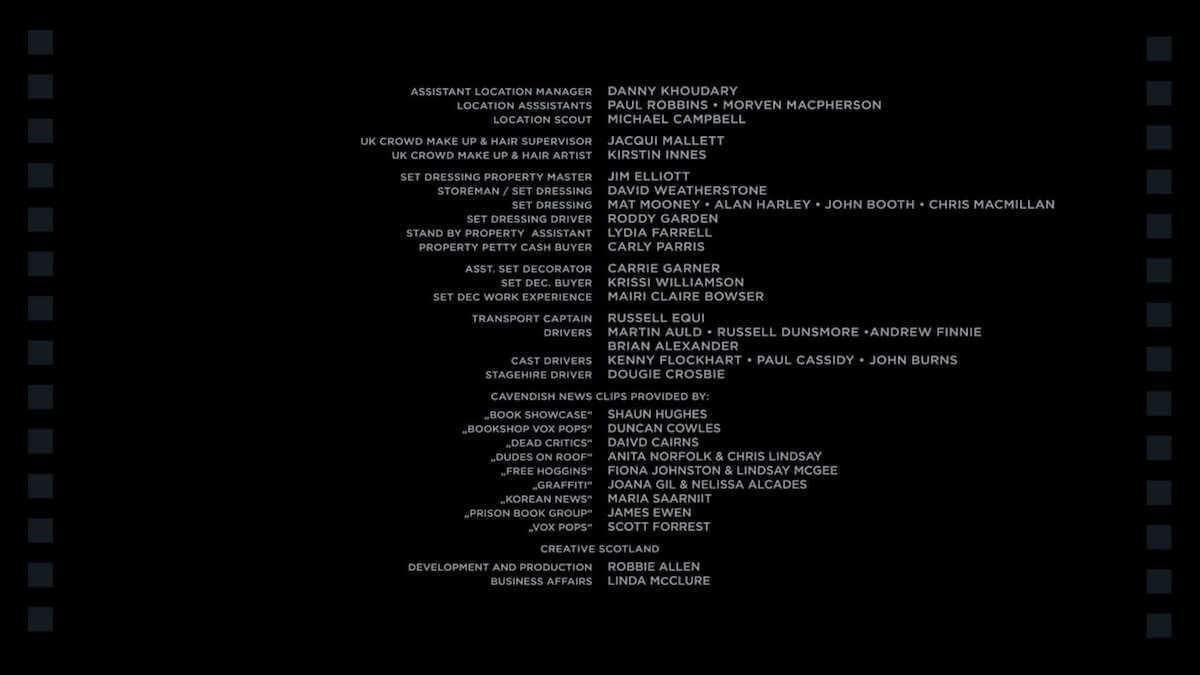

The expansion of Native American writing credits is particularly evident in television and film, an industry historically notorious for its egregious misrepresentation of Indigenous peoples. The groundbreaking success of Reservation Dogs, co-created by Sterlin Harjo (Seminole/Muscogee) and Taika Waititi (Māori), marks a pivotal moment. This comedy-drama, featuring an all-Indigenous writing staff, directors, and cast, offers an authentic, nuanced, and often hilarious portrayal of contemporary Native life in rural Oklahoma. Its critical acclaim and widespread popularity demonstrate that there is a vast, eager audience for stories told by Indigenous creators, free from the often-patronizing gaze of Hollywood. Shows like Dark Winds, with its Indigenous lead characters and significant Native involvement behind the scenes, further illustrate this welcome shift.

The importance of this resurgence cannot be overstated. Firstly, authentic Native American writing credits are crucial for reclaiming narrative sovereignty. For too long, the stories about Indigenous peoples were told by non-Indigenous people, often perpetuating harmful stereotypes or reducing complex cultures to simplistic caricatures. When Native writers tell their own stories, they dismantle these myths, offering multifaceted portrayals of joy, sorrow, resilience, struggle, and humor that reflect the true diversity of Indigenous experiences. As Joy Harjo often emphasizes, "The stories are in the land, and in the blood." When those who carry that blood and connection tell the stories, they carry an undeniable truth.

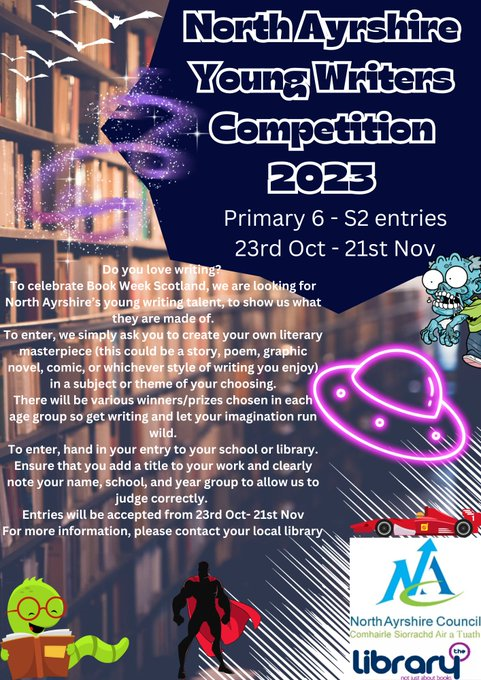

Secondly, these narratives serve as a vital tool for cultural preservation and revitalization. Many Indigenous languages and traditions have been suppressed or endangered. Native writers, whether writing in English or their ancestral languages, infuse their work with cultural references, traditional knowledge, and worldviews that help to keep these vital aspects of heritage alive and transmit them to younger generations. They validate Indigenous ways of knowing and being, fostering pride and connection within Native communities.

Thirdly, Native American writing offers profound insights into decolonization and healing. Many Indigenous communities are grappling with the intergenerational trauma of colonialism, residential schools, and systemic discrimination. Literature and art provide a space to process this pain, to explore resilience, and to imagine pathways toward healing and self-determination. Stories become acts of resistance, memory, and hope.

Finally, for non-Native audiences, these stories build empathy and understanding. By encountering Indigenous characters and narratives that are complex, relatable, and deeply human, readers and viewers are challenged to confront their own preconceived notions and to learn about histories and contemporary realities that have often been omitted from mainstream education. This fosters a more accurate and equitable understanding of American history and society, paving the way for more respectful relationships.

Despite this progress, significant challenges remain. Native American writers and stories are still vastly underrepresented in the publishing industry, Hollywood, and educational curricula. According to various reports, while the number of published authors of color has increased, Native American authors still represent a tiny fraction of the overall literary output. There’s often a burden of representation placed on individual Native writers, expected to speak for an entire diverse continent of nations, rather than being seen simply as individual artists with unique perspectives. Gatekeeping continues in the form of a lack of diverse editors, agents, and executives who understand and champion Indigenous narratives. Furthermore, the threat of cultural appropriation persists, with non-Native authors sometimes attempting to tell Indigenous stories without proper respect, research, or collaboration.

The path forward demands continued advocacy, systemic change, and unwavering support for Indigenous creators. This means investing in Native-led literary organizations, funding Indigenous arts initiatives, and actively seeking out and publishing a wider array of Native voices across all genres. It means nurturing emerging talent through mentorship programs and literary awards specifically for Indigenous writers. It also requires the industry to hire more Indigenous editors, agents, and producers who can advocate for these stories from within.

The resurgence of Native American writing credits is more than a trend; it is a profound historical correction. It signifies a long-overdue recognition of the enduring power, wisdom, and beauty embedded in Indigenous cultures. As Native voices continue to rise, they enrich the global literary tapestry with perspectives that are essential, urgent, and deeply resonant. Their stories remind us that the American landscape, far from being silent, has always vibrated with narratives waiting to be heard, offering profound lessons on resilience, connection to land, and the enduring human spirit. The silence is broken, and a new era of authentic, powerful storytelling has gloriously begun.