The Enduring Fire: Unveiling the Sacred Resilience of the Blackfoot Sun Dance

By [Your Name/Journalist Alias]

In the searing heat of a midsummer day on the vast, undulating plains of what is now Southern Alberta and Montana, a profound spiritual drama unfolds. Dust devils dance across the horizon, mirroring the energy building within a sacred lodge constructed of saplings and canvas. The rhythmic thrum of drums, ancient songs carried on the wind, and the scent of sweetgrass and sage blend into an intoxicating symphony. This is the Blackfoot Sun Dance, or Okan – a ceremony not merely observed, but deeply lived, embodying the very heart of the Siksikaitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy): the Siksika, Kainai (Blood), and Piikani (Peigan) nations.

More than just a ritual, the Sun Dance is a living prayer, a rigorous test of endurance, and a powerful act of community renewal. It is a testament to the unwavering spirit of a people who, despite centuries of colonial suppression, have held fast to the sacred fires of their ancestors.

A Legacy Forged in Time and Trial

The roots of the Blackfoot Sun Dance stretch back into time immemorial, long before European contact. It was, and remains, the central religious ceremony of the Plains Indigenous peoples, a communal gathering held annually during the summer when buffalo were plentiful and tribes could safely congregate. Its purpose was multifaceted: to give thanks, to pray for health and prosperity for the nation, to heal the sick, to fulfill vows, and to renew the spiritual connection between the people, the land, and the Creator, Napi (Old Man).

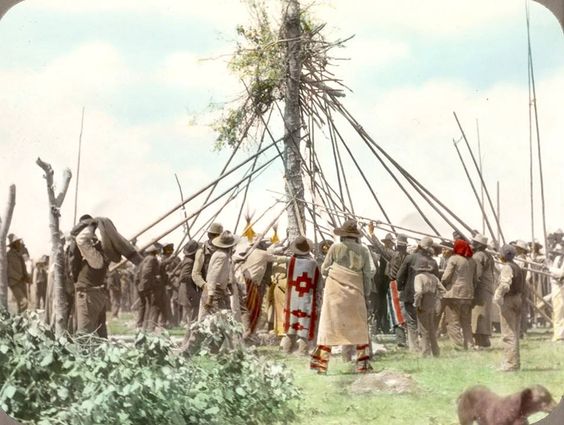

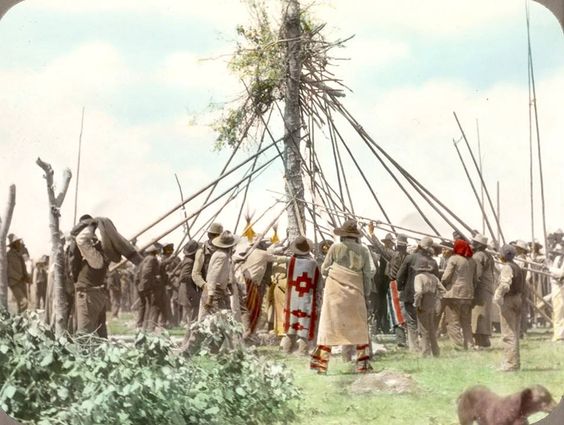

The ceremony, traditionally led by a holy woman (the Vower or Intercessor), involves days of fasting, continuous dancing, and profound spiritual introspection. The construction of the Okan lodge itself is a sacred act, with a central pole representing the Tree of Life, connecting the earth to the sky. Around this pole, participants dance, their movements a living prayer, their bodies becoming vessels for spiritual power.

However, the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought an existential threat to these vital practices. As part of a broader strategy of assimilation, the Canadian and U.S. governments enacted policies designed to eradicate Indigenous cultures. In Canada, the infamous Indian Act, particularly its amendments in 1884 and later, explicitly banned Indigenous spiritual ceremonies, including the Sun Dance.

"It was a deliberate attempt to break our spirit, to sever our connection to our land and our traditions," explains Elder Mary Many Feathers, a Kainai knowledge keeper. "They wanted us to forget who we were, to become like them. But our elders, our grandmothers and grandfathers, they kept the fire burning, sometimes in secret, always in their hearts."

During these dark times, the Sun Dance was forced underground. Families performed smaller, clandestine versions, risking imprisonment and persecution to ensure the continuity of their spiritual heritage. This period of suppression, coupled with the trauma of residential schools, caused immense suffering and cultural dislocation. Yet, the memory of the Okan persisted, a flickering ember waiting for the right conditions to reignite.

The Resurgence: A Nation Reclaiming Its Spirit

The lifting of the ban in 1951 in Canada, and a gradual shift in attitudes in the U.S., allowed the Sun Dance to emerge from the shadows. The Blackfoot nations, alongside other Indigenous communities, began the painstaking work of cultural revitalization. Elders, who had meticulously guarded the knowledge, began to openly teach the younger generations.

Today, the Blackfoot Sun Dance is a powerful symbol of resilience and cultural pride. While specific details of the ceremony remain sacred and are not openly discussed out of respect for their spiritual power, the core elements are visible to those invited to witness or participate.

The ceremony typically spans several days, often four, following an extensive period of preparation by the Vower and her family. The Vower, often a woman who has made a vow in a time of great need (e.g., for a sick child, for healing from trauma, for community well-being), plays a central role. She leads the spiritual preparations, guides the building of the lodge, and embodies the spiritual focus of the ceremony.

Participants, known as "dancers," commit to a period of intense spiritual and physical discipline. They fast from food and water for the duration of the dance, a profound act of purification and sacrifice. Their movements are deliberate, often accompanied by the resonating beat of the drum and the powerful, haunting melodies of traditional songs. Each step, each prayer, is offered for the collective good.

The Sacred Act of Offering

Perhaps the most misunderstood, and often sensationalized, aspect of the Sun Dance is the act of piercing. For some male participants, a small piece of skin on their chest is pierced, and ropes are attached to the central pole or buffalo skulls. The dancer then pulls against the ropes until the skin tears, releasing him. This is not, as often misconstrued, a test of pain endurance for its own sake, but rather a deeply personal and profound act of physical sacrifice – an offering of self to the Creator for the benefit of the community, for healing, for vision, or to fulfill a sacred vow.

"It’s the ultimate act of giving back," explains a young Blackfoot man who participated in the piercing ceremony last year. He asked not to be named, emphasizing the personal nature of the sacrifice. "You’re offering your body, your blood, your pain, for something bigger than yourself – for your family, for your nation, for the health of the land. It’s a prayer made flesh."

For women, their offerings are equally significant, often involving the arduous task of preparing the sacred bundles, crafting intricate regalia, and providing unwavering support to the dancers through prayer and song. The entire community plays a role: drummers and singers maintain the heartbeat of the ceremony, elders offer guidance and prayers, and families support their fasting relatives.

The buffalo, once the lifeblood of the Plains peoples, remains a potent symbol within the Okan. Buffalo skulls, representing the sacredness of life and the continuity of existence, are often placed within the lodge, reminding participants of the profound relationship between the people and the natural world.

A Living University

Beyond its spiritual dimension, the Sun Dance serves as a crucial institution for the transmission of Blackfoot knowledge, values, and identity. It is, in essence, a "living university" where oral traditions, history, songs, and spiritual protocols are passed down from generation to generation.

"Our Sun Dance is where our children learn what it truly means to be Siksikaitsitapi," says Elder Peter Bull Bear. "They see the sacrifice, they hear the songs, they feel the spirit. It teaches them patience, humility, generosity, and respect for all living things. It teaches them their place in the world."

In an era grappling with the ongoing impacts of intergenerational trauma from colonialism, the Sun Dance offers a powerful path to healing. It provides a space for individuals and the community to confront historical wounds, to find strength in their cultural heritage, and to reaffirm their identity in the face of ongoing challenges. The collective prayer and sacrifice are seen as crucial for the healing of the land and the people.

The Future of the Fire

Today, the Blackfoot Sun Dance continues to thrive, adapting to the modern world while meticulously preserving its ancient core. While some aspects remain highly sacred and private, there is also a growing understanding among non-Indigenous people of its importance. Invited guests, respecting the protocols and sacredness, are sometimes allowed to witness parts of the public ceremony, fostering understanding and reconciliation.

As the sun sets on the final day of the Okan, exhausted but spiritually renewed participants emerge from the lodge. They have danced, fasted, and prayed, offering their very selves to the Creator and to their community. The fire of the Sun Dance, though once threatened, burns brighter than ever, a beacon of resilience, cultural pride, and unwavering faith. It is a powerful reminder that the spirit of the Blackfoot people, like the sun itself, will always rise again.