Bleeding Kansas: The Crucible of Civil War

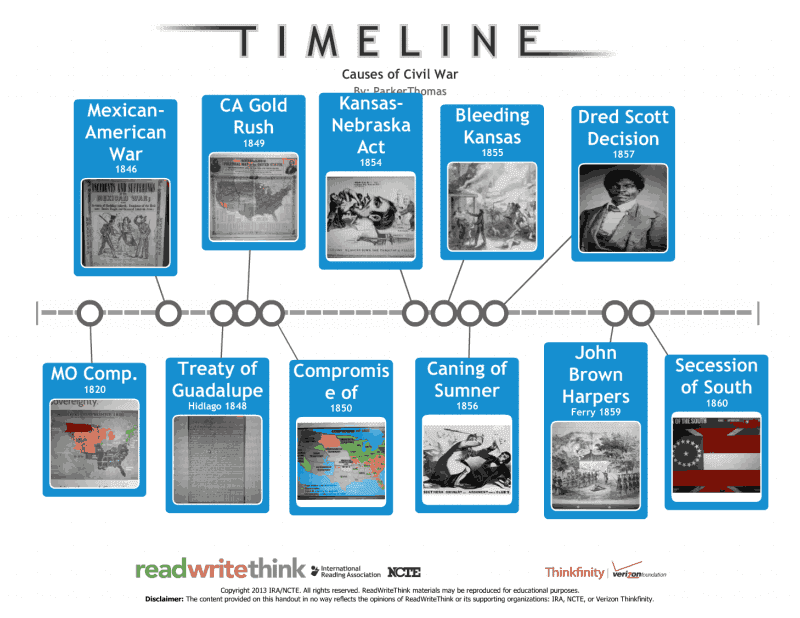

The mid-19th century United States was a nation increasingly fractured by the issue of slavery, a fault line running deeper than any river or mountain range. But it was in the vast, untamed prairies of the Kansas Territory that this simmering conflict truly ignited, transforming a political debate into a brutal, bloody dress rehearsal for the American Civil War. From 1854 to 1859, Kansas became a battleground, a crucible where the ideals of democracy clashed with the raw violence of sectionalism, earning it the grim moniker: "Bleeding Kansas."

This is the timeline of how a dream of popular sovereignty devolved into a nightmare of civil strife, leaving an indelible stain on the nation’s conscience and pushing it inexorably towards its deadliest conflict.

1854: The Spark – Popular Sovereignty and a "Hell of a Storm"

The stage for Kansas’s tragedy was set not by its settlers, but by the ambitions of a senator from Illinois, Stephen A. Douglas. In January 1854, Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act, a legislative bombshell designed to facilitate the construction of a transcontinental railroad and organize the remaining unorganized territories of the Louisiana Purchase. To appease Southern Democrats, the Act included a revolutionary and ultimately disastrous provision: "popular sovereignty." This doctrine declared that the residents of each territory, rather than Congress, would decide whether to permit slavery within their borders.

The Act explicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, effectively reopening the entire Western territory to the possibility of slavery. The reaction was immediate and fierce. Abolitionists and Free-Soilers in the North were outraged, viewing it as a blatant capitulation to the "Slave Power." Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, declared it "a crime against humanity." Even Southern moderates recognized the danger. As Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri famously warned, the Act would "array the two halves of the Union against each other, and do what no foreign enemy could do – hew it asunder in the midst." Douglas himself reportedly remarked, "I have passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, but I will raise a hell of a storm." He was tragically correct.

With the stroke of a pen, the race to settle Kansas began.

1855: The Race for Control – Two Constitutions, Two Governments

The promise of popular sovereignty turned Kansas into a political battleground before a single crop could be planted. Pro-slavery advocates, primarily from the neighboring slave state of Missouri, quickly dubbed "Border Ruffians," poured into Kansas. Their aim was to ensure, through any means necessary, that the territory would vote to become a slave state. They were met by an equally determined influx of anti-slavery settlers, often financed by organizations like the New England Emigrant Aid Company, which supplied them with rifles (known as "Beecher’s Bibles" after the abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher who advocated for arming free-state settlers) and resources.

The first critical test came with the territorial legislative elections of March 1855. Thousands of armed Border Ruffians crossed the border, cast illegal ballots, and then returned to Missouri. The result was a sham: over 6,300 votes were cast, despite there being only about 2,900 eligible voters. The pro-slavery legislature, elected through this fraud, convened in Lecompton and immediately passed a series of draconian laws, including one that made it a capital offense to aid an escaped slave and a felony to even question the legality of slavery in Kansas.

Free-state settlers, refusing to recognize the legitimacy of this "Bogus Legislature," convened their own constitutional convention in Topeka in October 1855. They drafted the Topeka Constitution, which prohibited slavery, and formed a parallel government, electing their own governor and legislature. Kansas now had two rival governments, each claiming legitimacy, each supported by armed factions, and each ready to defend its claims. This deeply unstable situation was a powder keg, waiting for a spark.

1856: The Year of Violence – "Bleeding Kansas" Erupts

The year 1856 marked the horrifying escalation from political maneuverings to open warfare. The fuse was lit on May 21, 1856, with the Sack of Lawrence. A pro-slavery posse, consisting of federal marshals and Border Ruffians, rode into the free-state stronghold of Lawrence, ostensibly to execute warrants. They destroyed the offices of the two free-state newspapers, ransacked homes, and burned the Free State Hotel. No lives were lost, but the attack was a profound psychological blow, demonstrating the vulnerability of the free-staters and the willingness of their opponents to use force.

The response was swift and brutal. Three days later, on the night of May 24-25, 1856, a radical abolitionist named John Brown, along with his sons and other followers, exacted a terrible revenge. Believing he was acting under divine command, Brown led his group to Pottawatomie Creek, where they dragged five pro-slavery settlers from their homes and hacked them to death with broadswords in front of their families. The Pottawatomie Massacre sent shockwaves through the territory, escalating the conflict from property destruction to cold-blooded murder. Brown’s actions, while condemned by many, also galvanized some free-staters and further demonized the abolitionist cause in the South.

The violence in Kansas was mirrored in the halls of power. On May 22, 1856, just two days after the Sack of Lawrence and one day before the Pottawatomie Massacre, South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks savagely beat Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner with a cane on the floor of the U.S. Senate. Sumner had delivered a fiery anti-slavery speech, "The Crime Against Kansas," in which he personally insulted Brooks’s cousin, Senator Andrew Butler. The Brooks-Sumner Affair revealed the depth of animosity and the breakdown of civility at the highest levels of government, confirming that the conflict was no longer confined to the remote prairies.

Throughout the rest of 1856, Kansas descended into a state of intermittent guerrilla warfare. Skirmishes like the Battle of Black Jack (where John Brown led a free-state force against pro-slavery raiders) and the Battle of Osawatomie (where Brown’s forces were defeated by a larger pro-slavery contingent) became common. Hundreds were killed or wounded, and property damage was extensive. President Franklin Pierce dispatched federal troops to restore order, but the damage was done. The experiment of popular sovereignty had failed, drowning in blood.

1857-1858: Political Turmoil and the Lecompton Controversy

While the intensity of direct violence somewhat abated after 1856, the political struggle continued with ferocity. The focus shifted to the Lecompton Constitution, drafted by the pro-slavery government in October 1857. This document, designed to make Kansas a slave state, was a cynical maneuver. It presented voters with a choice not to accept or reject slavery outright, but to vote "with slavery" or "with no slavery." Even if "with no slavery" passed, it protected existing slave property and allowed for continued importation. Free-staters, seeing through the trick, boycotted the vote. Unsurprisingly, the "with slavery" option passed easily with minimal turnout.

President James Buchanan, heavily influenced by Southern Democrats, made the disastrous decision to endorse the Lecompton Constitution and push for Kansas’s admission as a slave state. This move alienated a crucial figure: Stephen A. Douglas, the architect of popular sovereignty. Douglas, true to his belief in legitimate popular will, denounced the Lecompton Constitution as a fraud that violated the very principle he championed. His public break with Buchanan and the Southern wing of his Democratic Party was a monumental event, further fragmenting the national political landscape.

Congress ultimately rejected the Lecompton Constitution, sending it back to Kansas for a genuine popular vote. In August 1858, Kansans overwhelmingly rejected it by a margin of over 10,000 votes, finally putting an end to this particular pro-slavery scheme.

1859-1861: The Path to Statehood and the Civil War

With the Lecompton Constitution defeated, free-state forces in Kansas finally gained the upper hand. In July 1859, they drafted the Wyandotte Constitution, a definitively anti-slavery document that also granted women some rights, including property ownership and voting in school elections. This constitution was approved by popular vote in October 1859.

However, Kansas’s entry into the Union was delayed by the escalating national crisis. Southern states, increasingly fearful of losing their political power, blocked its admission. It was not until the secession of Southern states in early 1861, removing their representatives from Congress, that Kansas was finally admitted as a free state on January 29, 1861. The irony was profound: after nearly seven years of bloody struggle to prevent slavery, Kansas joined the Union just as the nation descended into civil war over that very issue.

The Legacy of Bleeding Kansas

"Bleeding Kansas" was more than just a localized conflict; it was a microcosm of the national struggle and a direct precursor to the Civil War. It demonstrated the utter failure of popular sovereignty as a solution to the slavery question, proving that the issue was too fundamental, too morally charged, to be resolved by local elections.

The violence in Kansas radicalized both sides. It transformed abolitionists like John Brown into figures willing to use extreme violence, foreshadowing the brutality of the coming war. It solidified the image of the "Border Ruffian" in the Northern mind and the "fanatical abolitionist" in the Southern mind, making compromise almost impossible.

The events in Kansas also contributed significantly to the rise of the Republican Party, which was founded on an anti-slavery platform. The party’s strong showing in the 1856 election and its victory in 1860, with Abraham Lincoln at the helm, directly stemmed from the outrage generated by the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the subsequent violence.

The cost of "Bleeding Kansas" was immense: an estimated 200 lives lost, millions of dollars in property damage, and a nation irrevocably scarred. It tore apart the fabric of American society, pitting neighbor against neighbor, and laid bare the deep-seated divisions that would soon plunge the country into its most devastating conflict. The fields of Kansas, once envisioned as a democratic testing ground, became the first battlefield in the long, bloody road to emancipation and national reunification.