/kansas-massacre-3435416-59cbf82bd088c000118c48be.jpg)

Bleeding Kansas: The Fiery Prelude to America’s Civil War

Before the cannons roared at Fort Sumter, before the Union and Confederate armies clashed in grand, bloody battles, America’s great national crisis found its proving ground in the vast, windswept prairies of Kansas. Here, from 1854 to 1861, the abstract debate over slavery erupted into a brutal, localized civil war, a conflict so savage it earned the grim moniker "Bleeding Kansas." This was not merely a skirmish; it was a microcosm of the national struggle, a dress rehearsal for the conflagration that would soon engulf the entire nation, leaving an indelible stain on the American landscape and psyche.

The stage for this unfolding tragedy was set by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, a legislative maneuver spearheaded by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. Designed to facilitate westward expansion and the construction of a transcontinental railroad, the Act delivered a bombshell: it repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel. In its place, Douglas championed the principle of "popular sovereignty," allowing the residents of each new territory to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery. For Kansas, a territory directly adjacent to the slave state of Missouri, this meant an immediate and violent struggle for its soul.

The promise of popular sovereignty, intended as a democratic solution, instead ignited a furious "race for Kansas." On one side stood the pro-slavery advocates, primarily from Missouri, who saw Kansas as a natural extension of their way of life. These were the "Border Ruffians," armed and often drunk, led by figures like Missouri Senator David R. Atchison. Atchison famously declared, "We will go to Kansas and kill every goddamned abolitionist we can find." Their aim was clear: to flood the territory, vote slavery into existence, and secure Kansas as a slave state.

Opposing them were the "Free-Staters" – anti-slavery settlers from New England and other Northern states, many aided by organizations like the New England Emigrant Aid Company, which provided financial support and weapons. These settlers, often called "Jayhawkers" by their enemies, were determined to prevent the expansion of slavery. They viewed Kansas as a battleground for freedom, a place where the moral imperative to stop slavery could be realized. Among them were idealistic farmers, lawyers, and even radical abolitionists who believed that only through direct action could the tide of slavery be turned.

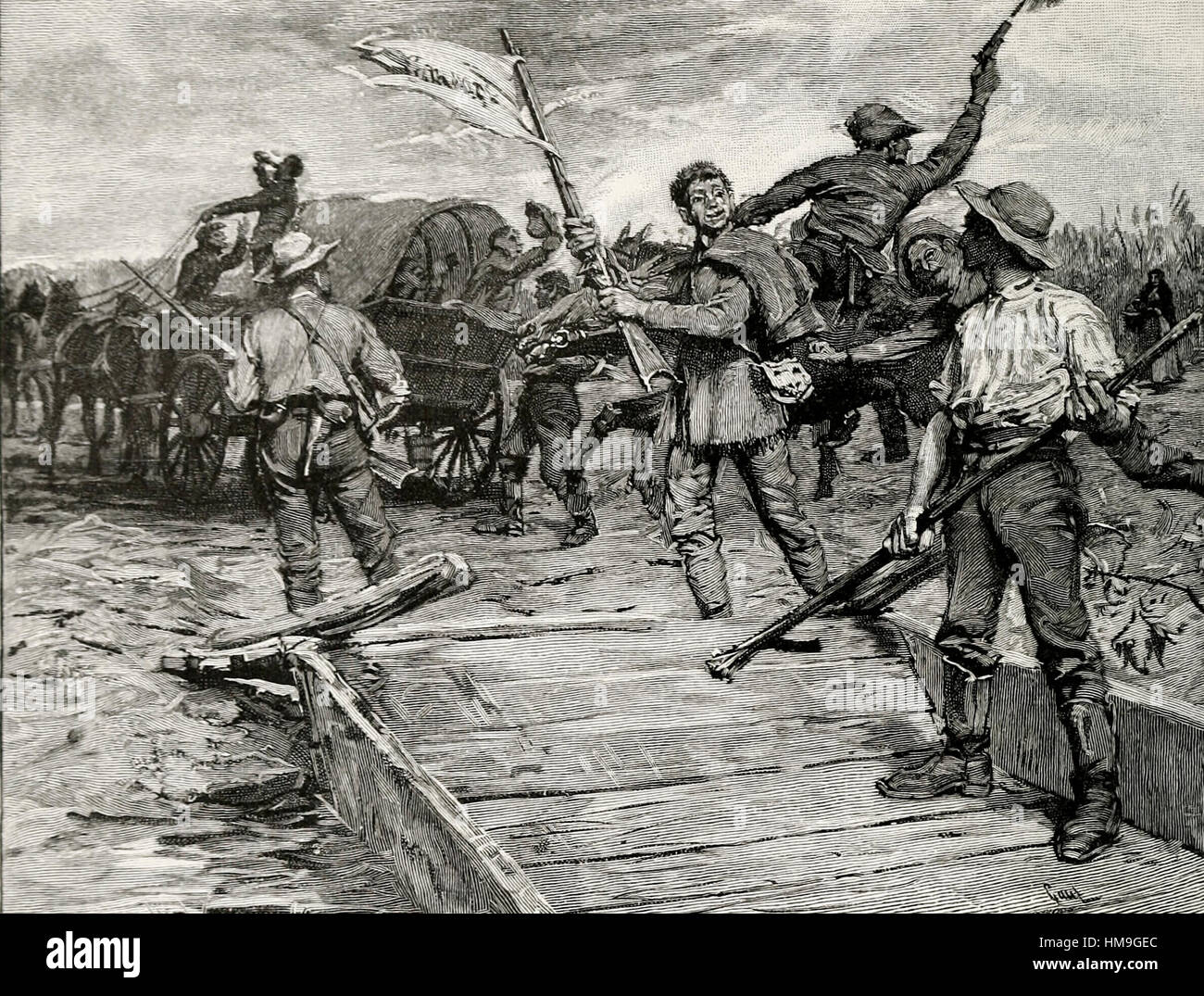

The initial phase of Bleeding Kansas was marked by electoral fraud and political chicanery. In the territory’s first elections, Border Ruffians from Missouri surged across the border, casting thousands of illegal votes to ensure pro-slavery majorities. One observer noted that on election day, "the Missourians were driving their wagons into Kansas with loads of men and whiskey, and a free-for-all was taking place at the polls." This resulted in the establishment of a pro-slavery territorial legislature in Lecompton, which immediately enacted harsh slave codes, including the death penalty for aiding runaway slaves.

The Free-Staters, refusing to recognize the legitimacy of the "Bogus Legislature," formed their own government in Topeka, drafted an anti-slavery constitution, and elected their own governor, Charles Robinson. Thus, by 1856, Kansas had two rival governments, each claiming legitimacy, each backed by armed partisans, and each vying for federal recognition. This dual power structure, born of fraud and defiance, created a volatile vacuum of authority, ripe for violence.

The simmering tensions erupted into open warfare in May 1856 with the "Sack of Lawrence." Lawrence, a stronghold of Free-Staters and a symbol of Northern resistance, became the target. A pro-slavery posse, inflamed by fiery rhetoric and the murder of a pro-slavery sheriff, marched on the town. They destroyed newspaper offices, burned the Free State Hotel, and ransacked homes. Though only one life was lost, the destruction was symbolic, sending shockwaves across the nation. The violence demonstrated that the conflict in Kansas was no longer merely political; it was a brutal, physical struggle for dominance.

News of the Sack of Lawrence profoundly affected one of the most iconic and controversial figures of the era: John Brown. A fervent abolitionist who believed he was an instrument of God’s will, Brown had arrived in Kansas with several of his sons, determined to fight slavery by any means necessary. The violence in Lawrence, coupled with a savage attack on Senator Charles Sumner in the U.S. Senate (prompted by his "Crime Against Kansas" speech), pushed Brown to a breaking point.

Three days after the Sack of Lawrence, Brown led a small band of men, including four of his sons, to Pottawatomie Creek. There, they dragged five pro-slavery settlers from their homes and brutally murdered them with broadswords. Brown saw this as divine retribution, an "eye for an eye" response to the atrocities committed against Free-Staters. The Pottawatomie Massacre, while a horrific act of terror, irrevocably escalated the conflict. It plunged Kansas into a full-blown guerrilla war, with both sides engaging in raids, ambushes, and targeted killings.

"Bleeding Kansas" continued for years with a relentless cycle of violence. Skirmishes like the Battle of Black Jack, where John Brown famously captured a pro-slavery leader, and the Battle of Osawatomie, where Brown’s forces were defeated by a larger pro-slavery militia, became common occurrences. In 1858, the Marais des Cygnes Massacre saw eleven Free-Staters captured by a pro-slavery gang, with five executed in cold blood. These acts of terror and reprisal solidified the hatred between the factions, making compromise all but impossible.

The political struggle continued alongside the bloodshed. The pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution, which sought to force slavery upon the territory, was fiercely debated in Washington, ultimately rejected by Congress due to its clear violation of popular will. Finally, after several failed attempts, the anti-slavery Wyandotte Constitution was adopted in 1859, paving the way for Kansas to enter the Union as a free state. However, the deeply divided national political landscape meant that Kansas’s admission was delayed.

It wasn’t until January 29, 1861, as the Southern states were already seceding from the Union, that Kansas finally achieved statehood, joining as a free state. This victory for the Free-Staters was hard-won, paid for in blood and years of strife. Yet, even with statehood, the violence in Kansas did not cease. The deep-seated animosities cultivated during Bleeding Kansas continued to fester, finding new expression during the national Civil War.

Perhaps the most enduring and tragic testament to this lingering hatred was Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence in August 1863. William Clarke Quantrill, a notorious Confederate guerrilla leader and former Border Ruffian, led a force of some 400 bushwhackers into Lawrence, seeking revenge for past Free-State atrocities. The raid was an act of pure terror: Quantrill’s men systematically burned the town, plundered homes, and murdered between 150 and 200 unarmed men and boys, many of whom were shot in cold blood. This horrific event, occurring well into the national Civil War, underscored the profound and personal nature of the Kansas conflict, a fight that transcended mere political ideology and became a brutal, generational vendetta.

The legacy of Bleeding Kansas is profound. It demonstrated, unequivocally, the utter failure of popular sovereignty as a solution to the slavery question. Instead of defusing the issue, it brought it to a violent head, proving that the expansion of slavery was a non-negotiable point for both sides. The events in Kansas hardened the resolve of abolitionists and anti-slavery forces across the North, providing vivid evidence of the barbarity of the pro-slavery cause. Conversely, it fueled Southern fears of Northern aggression and radicalism, convincing many that their way of life was under existential threat.

Abraham Lincoln, recognizing the immense significance of the Kansas ordeal, famously declared that it was "the first real battlefield of the great, decisive struggle." Indeed, Kansas served as a crucible, forging the ideological and physical battle lines that would soon divide the nation. The acts of courage and cruelty, the political maneuvering and popular uprisings, the moral righteousness and moral depravity that characterized Bleeding Kansas were all precursors to the larger national drama.

In the end, Bleeding Kansas was more than just a territorial dispute; it was the chilling overture to America’s most devastating conflict. It revealed the depth of the nation’s divisions, the ferocity of its convictions, and the tragic consequences when political compromise fails and the rule of law collapses. The blood spilled on the Kansas prairies was a harbinger of the immense sacrifice that would be demanded to cleanse the nation of its "original sin," leaving an enduring lesson about the fragility of peace and the enduring cost of freedom.