Blood on the White River: The Meeker Massacre and America’s Enduring Frontier Legends

The legends of America are etched into the very soil of the continent, tales of courage and conquest, of untamed wilderness and the relentless march of civilization. They speak of Manifest Destiny, of pioneers carving out a future, and of a "Wild West" where grit and gunfire shaped destinies. Yet, beneath the veneer of heroic narratives, these legends often conceal layers of complexity, conflict, and profound tragedy, particularly for the Indigenous peoples whose lands and lives were irrevocably altered. Few episodes encapsulate this intricate, often brutal, interplay of myth and reality more starkly than the Meeker Massacre of 1879 in the remote canyons of Colorado.

More than just a violent frontier skirmish, the Meeker Massacre became a pivotal moment, a catalyst that solidified anti-Ute sentiment in Colorado and directly led to the forced removal of the White River Ute people from their ancestral lands. It’s a story woven into the fabric of American memory, but one that, like many frontier legends, demands a critical re-examination to uncover the multifaceted truths buried beneath generations of one-sided accounts.

The Stage is Set: Land, Gold, and Conflicting Visions

By the late 1870s, Colorado was a land ablaze with ambition. The Pike’s Peak Gold Rush of 1859 had unleashed a torrent of prospectors and settlers, transforming a sparsely populated territory into a booming state hungry for resources and land. But much of western Colorado, a vast expanse of mountains, rivers, and fertile valleys, was still the treaty-guaranteed domain of the Ute Nation, an ancient people with a rich culture tied intrinsically to the land.

The Utes, a collective of several bands including the White River Utes, had long adapted to the changing landscape, but the pressure from encroaching white settlement was immense. Treaties, often signed under duress or misunderstanding, were repeatedly broken. The Utes watched as their hunting grounds diminished, their sacred sites were desecrated, and their traditional way of life was challenged at every turn.

Into this volatile environment stepped Nathan C. Meeker, an idealistic but profoundly misguided Indian Agent appointed in 1878 to the White River Ute Agency in northwestern Colorado. Meeker, a former newspaper editor and founder of the utopian Union Colony (now Greeley), arrived with a zealous vision: to "civilize" the Utes. His plan involved transforming them into sedentary farmers, cutting their long hair, banning their traditional horse racing and hunting, and instilling Christian values. "The sooner they begin to work, the sooner they will be self-supporting," Meeker declared, echoing a common refrain of the era that equated Indigenous self-sufficiency with adopting white agricultural practices.

Meeker’s intentions, though perhaps well-meaning from his own perspective, were deeply disrespectful and culturally insensitive to the Utes, who viewed his policies as an assault on their identity and autonomy. The Utes were skilled horsemen and hunters; farming, particularly the way Meeker demanded it, was seen as degrading. The land itself was sacred, not merely a commodity for tillage.

Tensions escalated quickly. Meeker, frustrated by the Utes’ resistance to his agricultural experiments, ordered the plowing of a large field, which included the Utes’ cherished horse racing track. This act was seen as a deliberate provocation, a direct attack on their culture and sovereignty. A physical altercation ensued between Meeker and a Ute named Johnson, further inflaming the situation. Fearing for his safety and convinced the Utes were "insolent" and "unruly," Meeker sent urgent dispatches to Washington D.C., requesting military assistance to enforce his will.

The Cataclysm of September 1879

Meeker’s pleas were answered. Major Thomas T. Thornburgh was dispatched from Fort Fred Steele in Wyoming with a column of 175 soldiers and supply wagons, ordered to investigate the situation and restore order at the agency. The Utes, however, viewed the advance of armed troops onto their treaty lands as an act of war. They had been promised that no troops would enter their reservation without their consent, a promise now being brazenly broken.

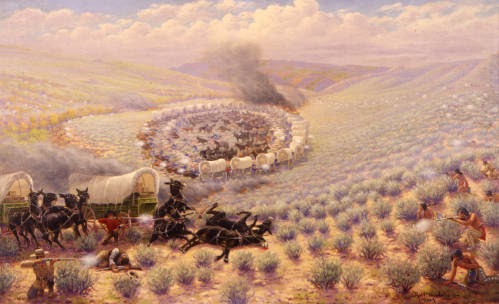

On September 29, 1879, as Thornburgh’s column approached Milk Creek, just north of the agency, they were ambushed by a group of Ute warriors. The Battle of Milk Creek, also known as Thornburgh’s Defeat, erupted. Thornburgh and ten of his men were killed in the initial assault, and the remaining soldiers were pinned down under siege for five days until reinforcements arrived. The Utes, fighting fiercely to defend their homeland, inflicted significant casualties on the U.S. troops.

Simultaneously, at the White River Agency, the situation devolved into horrific violence. The news of the Milk Creek engagement, combined with simmering resentments, triggered an attack by a different group of Utes on the agency personnel. Nathan C. Meeker and ten other men, including his employees and visitors, were killed. Their bodies were mutilated, reflecting the profound rage and desperation of the Utes who felt their way of life was under existential threat. Meeker himself was found with a stake driven through his mouth, a grim symbol of his attempts to force his words and will upon a people who refused to listen.

Among the dead were also Meeker’s wife, Arvilla, and his daughter, Josephine, who along with other women and children, including Flora Ellen Price and her two children, were taken captive by the Utes. For 23 harrowing days, these women endured captivity, moved from camp to camp, their fate uncertain.

The Aftermath: Panic, Politics, and Forced Removal

News of the "Meeker Massacre" and "Thornburgh’s Defeat" sent shockwaves across Colorado and the nation. Newspapers, eager to sensationalize the events, painted lurid pictures of "savage Indians" brutally murdering innocent white settlers. The public outcry was immense, fueled by existing prejudices and the insatiable demand for Ute lands. Cries of "The Utes Must Go!" became a rallying cry throughout the state.

Amidst the chaos and calls for retribution, one figure emerged as a beacon of diplomacy: Chief Ouray, leader of the Uncompahgre Utes, often called "The White Man’s Friend" for his efforts to bridge the gap between his people and the U.S. government. Ouray, though not directly involved in the White River incidents, understood the catastrophic implications. He immediately used his influence to secure the release of the captive women and children, sending his wife, Chipeta, a woman of remarkable courage and intelligence, to negotiate their freedom. Chipeta, along with other Ute leaders, successfully secured the captives’ release in mid-October, escorting them to safety at the Los Piños Agency.

Despite Ouray’s efforts and the release of the captives, the political will for Ute removal had reached a fever pitch. The "Meeker Massacre" provided the perfect pretext. Colorado’s powerful senators and politicians, backed by public sentiment and the promise of vast new lands for mining and settlement, pushed aggressively for a "solution" to the "Ute problem."

In 1880, Congress passed the Ute Agreement, a treaty that, under intense pressure and with little real negotiation, forced the White River Utes and the Uncompahgre Utes to cede nearly all of their remaining lands in Colorado. The White River Utes were relocated to a reservation in Utah, while the Uncompahgres were moved to a smaller reservation in southwestern Colorado. The Southern Utes were also impacted, losing significant territory. The Utes, a people who had once claimed a vast territory stretching across four modern states, were now confined to isolated pockets of land, their traditional way of life shattered.

The Enduring Legends and Their Reinterpretation

The Meeker Massacre swiftly entered the pantheon of American frontier legends, shaping perceptions of Indigenous peoples for generations. In the dominant narrative, it was a clear-cut case of "savage" resistance to "civilization," a justification for Manifest Destiny and the necessity of removing "obstacles" to progress. Nathan Meeker was often portrayed as a martyr, a benevolent reformer tragically undone by the intractable nature of the "Indian problem." The Utes were demonized, their actions stripped of context and reduced to mere barbarity.

However, a deeper, more nuanced understanding reveals a far more complex truth. The "massacre" was not an unprovoked act of savagery but the desperate, violent response of a people pushed to their breaking point. It was a reaction to systematic cultural destruction, broken treaties, and the relentless encroachment on their lands and sovereignty. Meeker, while perhaps driven by a desire to "help" the Utes, was ultimately an agent of their oppression, imposing his cultural biases with a heavy hand. His idealism was blind to the Ute perspective, leading directly to the tragedy.

Today, the town of Meeker, Colorado, stands as a quiet testament to this fraught history. The White River Museum preserves artifacts and tells parts of the story, but the landscape itself whispers of a more profound and painful past. For the Ute people, the Meeker Massacre and the subsequent removal are not just historical events but living memories of profound injustice, cultural loss, and enduring resilience. Their legends speak not of savagery but of defense, of broken promises, and of the strength to survive against overwhelming odds.

The story of the Meeker Massacre forces us to confront the uncomfortable truths embedded within America’s frontier legends. It challenges the simplistic narratives of heroes and villains, urging us to recognize the humanity and motivations on all sides. It reminds us that "progress" often came at an immense human cost, and that the legends we tell ourselves about our past reveal as much about our present values as they do about the events themselves. By understanding the full, complex story of Blood on the White River, we begin to truly grapple with the enduring legacy of the American frontier and the ongoing journey toward a more inclusive and truthful national memory.