Bloody Saturday in St. Louis: How the Camp Jackson Affair Ignited Missouri’s Civil War

ST. LOUIS, MO – May 10, 1861. A day that began with the promise of a warm spring afternoon quickly devolved into a maelstrom of gunfire, panic, and death. In the bustling streets of St. Louis, a city teetering on the brink of civil war, a single, bloody incident would rip away any lingering hope of neutrality for Missouri, plunging the state headlong into one of the most brutal and protracted conflicts of the American Civil War. This was the Camp Jackson Affair, a pivotal moment often overshadowed by larger battles, yet one that fired the first shots of a homegrown war that would scar Missouri for generations.

The air in St. Louis in early 1861 was thick with apprehension. Missouri, a border state with deep economic ties to both the industrial North and the agrarian, slaveholding South, found itself in an agonizing dilemma. Its population was a volatile mix of fervent Unionists, ardent secessionists, and a significant German immigrant community largely sympathetic to the Union cause. As states across the South declared their secession and Fort Sumter fell, Missouri’s precarious balance threatened to shatter.

At the heart of this tension was the St. Louis Arsenal, a vital federal installation housing some 60,000 stands of arms and vast quantities of ammunition. Control of this arsenal was paramount. On one side stood Missouri’s secessionist governor, Claiborne Fox Jackson, a man determined to pull his state out of the Union. On the other, a determined cadre of Unionists, led by Congressman Frank Blair Jr. and the fiery, uncompromising Captain Nathaniel Lyon of the U.S. Army.

The Powder Keg Takes Shape

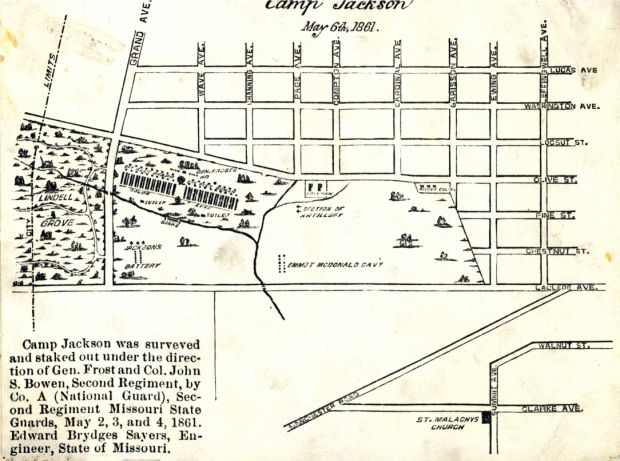

Governor Jackson, under the guise of training the state militia, ordered the annual encampment of the Missouri Volunteer Militia (MVM) just outside St. Louis, at an area quickly dubbed "Camp Jackson." Commanded by Brigadier General Daniel M. Frost, the camp began to take on a distinctly pro-Confederate character. Rumors, soon confirmed by intelligence, began to circulate: arms, including cannons and muskets, were being secretly shipped from Confederate states, particularly from the arsenal captured at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and covertly delivered to Camp Jackson.

This covert activity did not escape the notice of Captain Lyon. A diminutive, red-bearded firebrand, Lyon was a man of action and deep conviction. He distrusted Governor Jackson and his militia implicitly, viewing Camp Jackson not as a legitimate training exercise, but as a staging ground for a secessionist takeover of the St. Louis Arsenal. Lyon, with Blair’s backing, had already taken decisive steps to secure the arsenal, secretly transferring much of its valuable ordnance across the Mississippi River to Illinois, ensuring it wouldn’t fall into secessionist hands. He also organized and armed loyal Unionist Home Guard regiments, composed largely of German-American immigrants, who formed the backbone of St. Louis’s Union defense.

"Lyon was convinced that Governor Jackson was simply biding his time, preparing for a full-scale assault on the arsenal," noted historian William L. Parrish. "He saw Camp Jackson as a direct threat, a Trojan Horse."

On May 9th, Lyon, disguised as an elderly woman, reportedly wearing a veil and carrying a basket, conducted a personal reconnaissance of Camp Jackson. What he saw confirmed his gravest suspicions: cannons positioned to bear on the arsenal, the tell-tale crates of Confederate arms. His mind was made up. He would act decisively.

The Fuse is Lit: May 10th, 1861

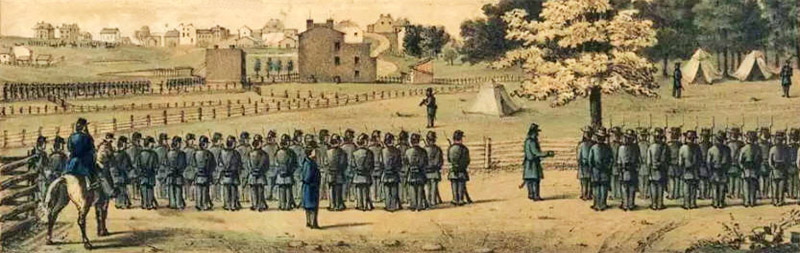

The morning of May 10th dawned uneventfully, but beneath the surface, St. Louis was a coiled spring. At 3 PM, Captain Lyon, without orders from Washington but with the full support of Frank Blair, marched approximately 6,000 Union troops – a mix of regular army soldiers and the hastily organized Home Guards – towards Camp Jackson. The sheer size of the force was overwhelming.

The troops surrounded the camp, blocking all exits. General Frost, surprised but facing insurmountable odds, knew resistance was futile. Lyon sent a demand for immediate surrender, citing the militia’s "open hostilities against the Government of the United States" and the "evident design of seizing the United States Arsenal." Frost, protesting the accusations, nonetheless capitulated. The 635 militiamen at Camp Jackson laid down their arms.

The surrender itself was bloodless, but the stage was set for tragedy. Lyon, perhaps miscalculating the volatile mood of the city, decided to march the disarmed prisoners through the streets of St. Louis to the arsenal, rather than transport them by river or wagon. This decision proved catastrophic.

The Explosion: "Bloody Saturday"

As the column of Union soldiers, flanking their disarmed prisoners, snaked its way through the crowded streets, curious onlookers, Union sympathizers, and ardent secessionists lined the sidewalks. The mood was a volatile mix of jubilation, resentment, and raw tension. The largely German-American Home Guards, many of whom spoke little English, were subjected to a barrage of insults, taunts, and even thrown objects from parts of the crowd.

"The air was thick with shouts and curses," reported one contemporary account. "Children and women mingled with angry men, their faces contorted with rage."

As the procession reached Olive Street, near 5th Street, chaos erupted. Accounts differ wildly on the precise trigger. Some claim a drunken man in the crowd fired a pistol at the troops. Others say a stray shot, or even a firecracker, ignited the panic. What is certain is that a shot was fired, followed by a fusillade from the Home Guards into the dense crowd.

The result was horrific. Men, women, and children screamed as they fell. The street became a scene of pandemonium. When the smoke cleared, at least 28 people lay dead, most of them civilians, including women and children. Dozens more were wounded. The Camp Jackson Affair, a bloodless capture, had transformed into the "Camp Jackson Massacre" in the eyes of many.

The Fallout and its Ramifications

The immediate aftermath was one of shock and outrage. The next day, St. Louis was gripped by mob violence. More clashes between citizens and Union troops occurred, resulting in additional fatalities. Lyon, facing a city on the brink of open rebellion, declared martial law.

The incident irrevocably shattered any remaining illusion of Missouri’s neutrality. Governor Jackson, now incandescent with rage, publicly denounced Lyon’s actions as "unparalleled outrages" and "atrocious acts." He intensified his efforts to align Missouri with the Confederacy.

A brief, uneasy truce was attempted between Major General William S. Harney (Lyon’s superior, a more conciliatory figure) and Sterling Price (who would soon become a prominent Confederate general). Known as the "Price-Harney Truce," it sought to keep Missouri out of the war by giving state authorities control over internal security. However, Lyon vehemently opposed it, seeing it as a capitulation to secessionists. He undermined Harney at every turn, ultimately leading to Harney’s removal and Lyon’s promotion to brigadier general.

The true end of Missouri’s neutrality came on June 11, 1861, at a tense meeting between Lyon, Frank Blair, Governor Jackson, and Sterling Price at the Planter’s House Hotel in St. Louis. Jackson demanded that Lyon disband his Home Guards and respect the state militia. Lyon, now in command, responded with an iconic and defiant declaration: "Rather than concede to the State of Missouri the right to demand that my Government shall not enlist troops in the State, or shall not put down rebellion within her borders… I will suffer my right arm to be torn from my body. Not one man shall be withdrawn! This means war!"

With those words, Lyon left the room, effectively launching the Civil War in Missouri. Governor Jackson and Price fled the city, beginning the process of raising a Confederate army for the state.

A Scarred Legacy

The Camp Jackson Affair served as the catalyst for Missouri’s brutal "Border War." Unlike other states, where the lines were often drawn clearly, Missouri became a deeply divided battlefield where neighbor fought neighbor, often with extreme ferocity. The state saw more battles and skirmishes than any other state except Virginia and Tennessee. It also became the epicenter of vicious guerrilla warfare, with figures like William Quantrill and Bloody Bill Anderson leading raids that terrorized both Unionists and secessionists.

The incident also had a profound impact on the German-American community in St. Louis. Having largely rallied to the Union cause, they were often scapegoated and blamed for the "massacre," fueling ethnic tensions that would persist for years.

Nathaniel Lyon, the architect of the Camp Jackson seizure, would go on to command Union forces in Missouri, leading them to victory at the Battle of Boonville, but would ultimately be killed leading his troops at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in August 1861, becoming the first Union general to die in the war.

The Camp Jackson Affair, often relegated to a footnote in the grand narrative of the Civil War, was anything but minor. It was a dramatic, bloody episode that, in a single afternoon, tore apart the fabric of Missouri society, ensured its place as a crucial and contested border state, and set the stage for four years of relentless conflict. "Bloody Saturday" in St. Louis was not just a local tragedy; it was the spark that ignited Missouri’s own deeply personal and devastating civil war.