Echoes from the Earth: The Resilient Revival of Catawba Pottery

ROCK HILL, South Carolina – In the red clay heartland of the Carolinas, where the Catawba River winds its ancient path, an enduring tradition is not merely surviving but thriving. For centuries, the Catawba Nation, one of the few federally recognized tribes in South Carolina, has been synonymous with its distinctive, coil-built pottery. Crafted without the aid of a potter’s wheel and fired in open pits, these vessels are more than mere objects; they are living testaments to an unbroken lineage, a deep spiritual connection to the land, and the indomitable spirit of a people who have defied erasure.

Yet, this vibrant art form, once the bedrock of Catawba identity and economy, faced a precipitous decline in the 20th century. Assimilation pressures, the lure of manufactured goods, and the slow erosion of traditional knowledge pushed the ancient craft to the brink of extinction. Today, however, thanks to the tireless dedication of matriarchs, cultural preservationists, and a new generation embracing their heritage, Catawba pottery has experienced a powerful resurgence, echoing the resilience of the earth itself.

A Legacy Forged in Clay and Fire

The story of Catawba pottery begins millennia ago. Archaeological evidence suggests the art form has been practiced by the Catawba and their ancestors for at least 4,000 years, making it one of the oldest continuous pottery traditions in North America. Unlike many other Southeastern tribes who adopted European pottery techniques or abandoned the craft entirely, the Catawba tenaciously held onto their distinct methods.

Their process is deeply rooted in the natural world. The distinctive reddish-brown clay, often sourced from traditional riverbeds and deposits along the Catawba River, is carefully dug, cleaned, and processed by hand. It is a laborious process, often involving sifting out impurities and working the clay until it reaches the perfect consistency. "The clay itself holds memory," explains Nola Blue, a contemporary Catawba potter whose family lineage traces back generations of potters. "It remembers the hands that shaped it, the water that mixed it, and the earth it came from. When we work with it, we’re not just making a pot; we’re communing with our ancestors."

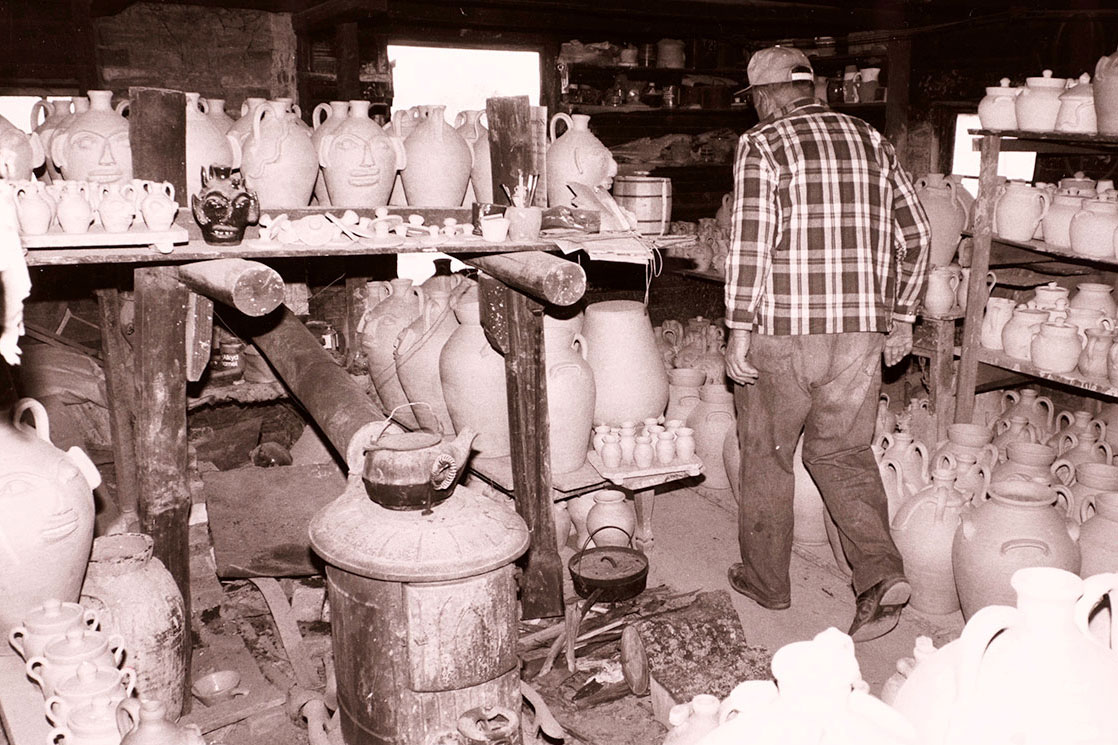

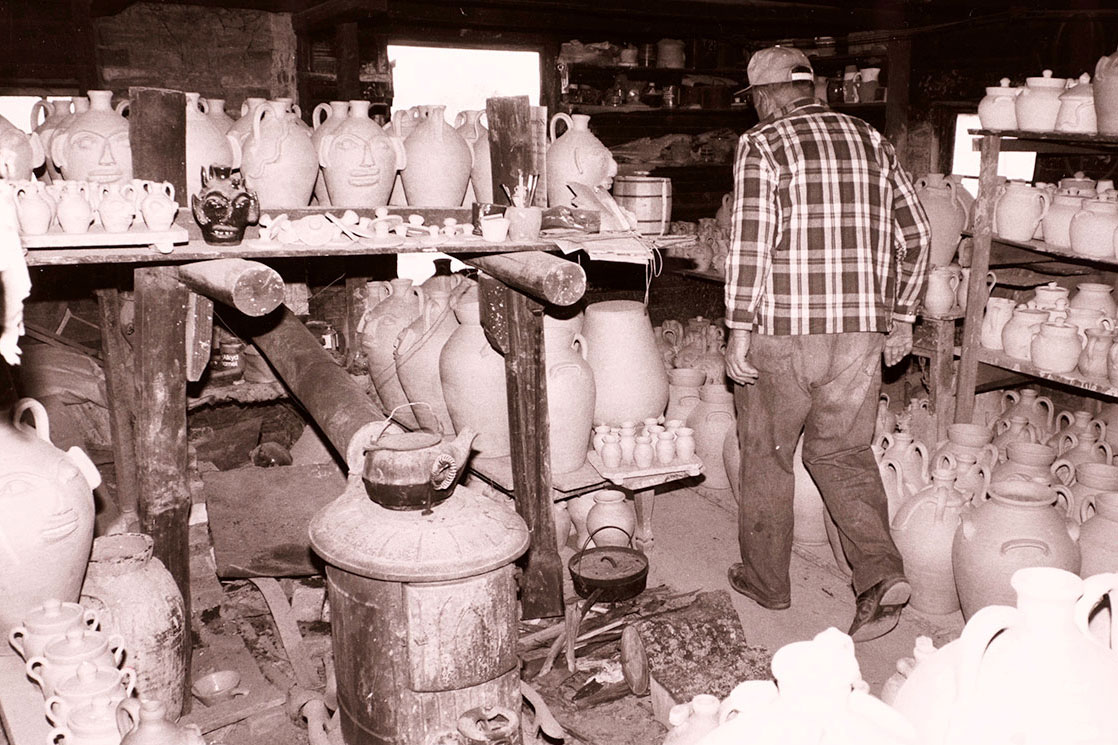

The traditional method involves no potter’s wheel. Instead, artisans use the "coil and scrape" technique. Coils of clay are meticulously stacked and joined, then smoothed and thinned with tools made from river cane, gourds, or even ancient mussel shells. The forms are typically utilitarian – storage jars, cooking pots, bowls, and pipe bowls – but each piece possesses an inherent elegance and unique character, a reflection of the individual potter’s touch.

Perhaps the most iconic aspect of Catawba pottery is its firing process. Unlike glazed ceramics, Catawba pots are fired in open pits, often fueled by wood, bark, and dried dung. This low-temperature firing, typically ranging from 900 to 1200 degrees Fahrenheit, imparts a characteristic mottled finish – shades of black, gray, and brown from the smoke and reduction firing, contrasting with the natural reddish-orange of the clay. The absence of glaze means the pots remain porous, allowing them to "breathe" – a quality highly valued for storing water and food.

The Brink of Disappearance

Despite its deep roots, the 19th and 20th centuries presented existential threats to Catawba pottery. The tribe, drastically reduced in numbers by disease and warfare, was pushed onto a small reservation. Their traditional lands were encroached upon, and the very resources necessary for their craft became scarce. The federal government’s assimilation policies actively discouraged Indigenous languages, religions, and cultural practices, including traditional arts. Children were sent to boarding schools where they were taught to abandon their heritage in favor of "American" ways.

Economic pressures also played a significant role. Factory-produced goods became cheaper and more readily available, diminishing the market for handmade pottery. The skill, once passed down effortlessly from mother to daughter, became a niche pursuit. By the mid-20th century, only a handful of elders, primarily women, continued to practice the art. "There was a time when our pots were everywhere, in every home," recalls the late Sarah Ayers (1921-2016), a revered matriarch and one of the most influential figures in the pottery revival, in a historical interview. "Then, suddenly, the interest faded. My mother and grandmother kept making them, but it was harder to sell. We almost lost it."

Ayers herself learned the craft from her mother, Eliza Canty Ayers, and her grandmother, Martha Jane Harris Canty. She understood the profound cultural significance of the pottery beyond its economic value. "It’s not just dirt; it’s our history, our spirit," she often said. "If we lose the pottery, we lose a piece of who we are."

The Flames of Revival

The spark for the modern revival of Catawba pottery can be largely attributed to the foresight and dedication of individuals like Sarah Ayers and her contemporaries, who refused to let the flame extinguish. In the latter half of the 20th century, as interest in Native American arts and cultural preservation grew, Ayers and others began to receive recognition and support. Museums sought out their work, and collectors recognized the unique beauty and historical importance of Catawba pottery.

Crucially, Ayers dedicated herself to teaching. She held workshops, demonstrated her techniques, and, most importantly, patiently instructed younger generations within her family and the wider Catawba community. She was a living bridge to the past, ensuring that the intricate knowledge of clay sourcing, preparation, coiling, shaping, and pit-firing was meticulously passed on.

The Catawba Nation itself played a pivotal role in institutionalizing the revival. Recognizing pottery as a cornerstone of their identity, the tribe invested in cultural preservation programs. They supported potters, facilitated access to traditional clay sources (even negotiating with landowners for access to ancestral clay pits), and established the Catawba Cultural Preservation Project, which includes a museum and cultural center that showcases tribal history and art, including pottery.

Challenges and Triumphs of a Living Tradition

Today, the Catawba pottery tradition is robust, but not without its challenges. The primary obstacle remains access to suitable clay. While the Catawba River basin still yields the specific iron-rich, fine-grained clay preferred by potters, development and private land ownership have restricted access to traditional digging sites. Potters often rely on relationships with landowners or travel further afield to find appropriate deposits.

Another challenge is balancing tradition with the demands of a contemporary market. While many potters adhere strictly to the ancient coil and pit-firing methods, some experiment with modern kilns for durability or to achieve different aesthetic effects, though the "true" traditionalists generally prefer the pit-fired pieces. This ongoing dialogue within the community highlights the dynamic nature of a living art form – how much to innovate, how much to preserve.

Despite these hurdles, the triumphs are evident. There are now dozens of active Catawba potters, including several who have achieved national recognition. Billy Blue, a descendant of Sarah Ayers, is one such artist, known for his masterful technique and dedication to teaching. "It’s more than just a craft; it’s a way of life, a way to connect with who we are as Catawba people," Blue states. He, like many others, regularly teaches workshops, ensuring that the next generation – children and adults alike – have the opportunity to learn.

The pots themselves have found a wider audience. They are displayed in prestigious museums across the country, including the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, and sought after by collectors. This recognition not only provides economic support for the artists but also elevates the visibility and appreciation of Catawba culture on a broader scale.

The Future in Their Hands

The future of Catawba pottery looks promising, shaped by hands both old and new. The tribal cultural center regularly hosts pottery classes, open to both Catawba citizens and the public, creating a vibrant learning environment. Younger Catawba artists are bringing fresh perspectives, sometimes incorporating new designs or pushing the boundaries of traditional forms while remaining rooted in the core techniques and philosophy.

The revival of Catawba pottery stands as a powerful testament to cultural resilience. It is a story not just of clay and fire, but of identity, memory, and the enduring power of community. Each pot, with its earthy aroma and unique markings from the pit fire, carries the whispers of ancestors, the strength of those who preserved the knowledge, and the hopes of a people determined to keep their heritage alive for generations to come. In every finished piece, the echoes of the earth continue to resonate, strong and clear.