Centralia: The Ghost Town Consumed by an Unseen Inferno

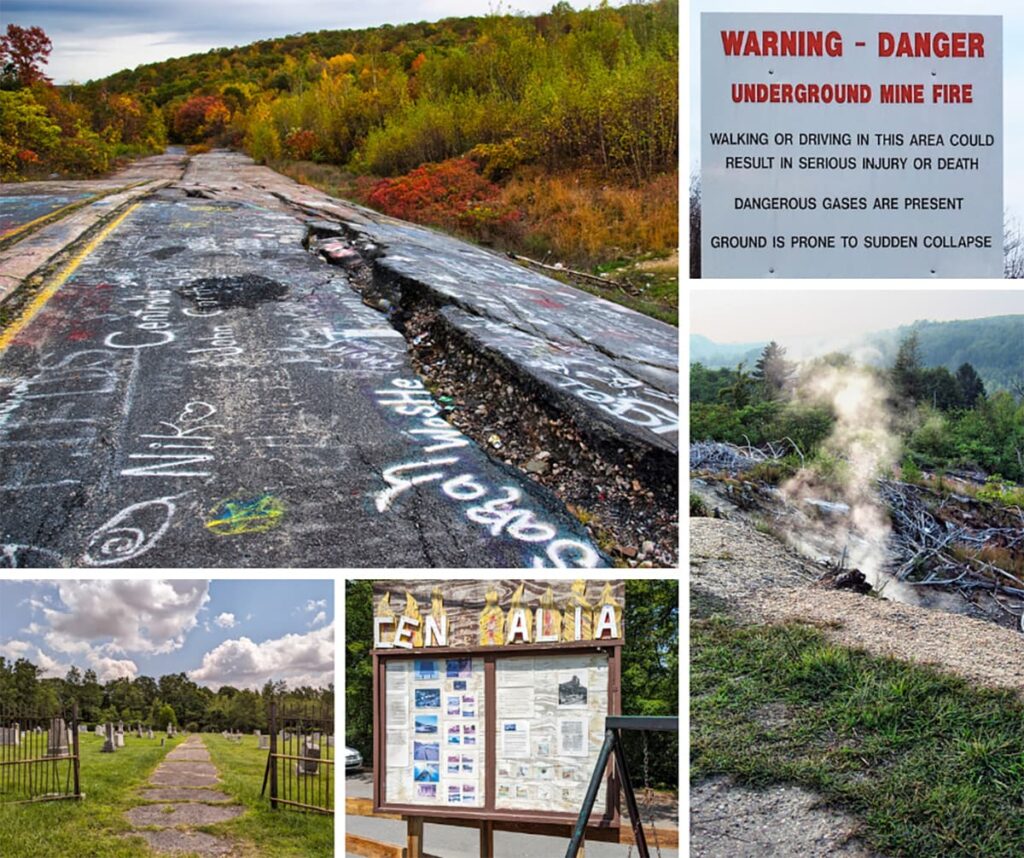

Beneath the verdant, rolling hills of Pennsylvania, a town is dying a slow, fiery death that began over six decades ago and is predicted to continue for centuries more. Centralia, once a bustling coal mining community in Columbia County, is now little more than a post-apocalyptic landscape of buckling roads, steaming vents, and a handful of defiant residents clinging to the ashes of their former lives. It is a place where the ground breathes smoke, the air carries the faint scent of sulfur, and the silence is occasionally broken by the hiss of subterranean flames – a chilling testament to human miscalculation and the enduring power of nature, even when provoked.

The story of Centralia is not one of sudden catastrophe but of a gradual, insidious decay, a slow-motion disaster that unfolded over decades. It began, innocently enough, in May 1962. The town council, in preparation for Memorial Day, authorized the burning of a trash dump located in an abandoned strip mine pit. This was a common practice at the time, a routine chore for many small towns. However, Centralia’s dump was no ordinary landfill. It sat atop a vast, interconnected network of abandoned anthracite coal mines, a labyrinth of shafts and tunnels that snaked beneath the entire borough.

The fire, ignited by the burning trash, found its way through an unsealed opening into the labyrinthine coal veins below. What started as a surface blaze quickly transformed into a subterranean inferno, feeding on the rich deposits of anthracite – a particularly dense and carbon-rich form of coal. Initial attempts to extinguish the fire were rudimentary and ultimately futile. Firefighters pumped water into the ground, dug trenches, and tried to smother the flames with clay, but the fire had already burrowed deep, following the coal seams like a hungry predator. "They thought it was just a simple dump fire," recalled former resident John Coddington, whose family was among the last to remain, "They had no idea what they were dealing with."

For years, the underground fire smoldered, largely out of sight and, for many, out of mind. Residents reported occasional wisps of smoke rising from the ground, the smell of sulfur, and unusually warm patches of earth. These were often dismissed as quirks of living in a mining region. However, by the late 1970s and early 1980s, the signs became undeniable and increasingly alarming. The ground began to sink in places, forming dangerous fissures and sinkholes. Trees died, their roots scorched by the intense heat. Carbon monoxide, a colorless and odorless killer, began to seep into homes, triggering alarms and causing health problems.

The most dramatic incident occurred in 1981 when a 12-year-old boy named Todd Domboski was playing in his grandmother’s backyard. The ground beneath him suddenly gave way, opening a 150-foot-deep sinkhole that swallowed him whole. He miraculously clung to a tree root until his cousin pulled him to safety, but the incident served as a terrifying wake-up call. The ground, it was clear, could no longer be trusted. Temperatures in some vent areas were recorded at over 1,000°F (538°C), hot enough to turn water to steam instantly.

The federal government finally took notice, though not without considerable debate and delay. Various state and federal agencies studied the problem, attempting to devise a solution. Several multi-million dollar plans were proposed, including digging up the entire town and filling the mines, or flooding the network with water, but each was deemed either too expensive, too dangerous, or ultimately ineffective against a fire of such immense scale and depth. "It was like trying to put out a forest fire by watering the leaves," one exasperated official reportedly said, highlighting the difficulty of reaching the deep-seated blaze.

In 1984, the U.S. Congress allocated $42 million for a voluntary relocation program. The decision was agonizing for Centralia’s approximately 1,000 residents. This was their home, their heritage, a place where generations had lived and worked. Many were deeply rooted, their lives intertwined with the community. But the threat was real and growing. Homes were condemned, properties purchased, and one by one, families began to leave, carrying with them not just their possessions, but the painful memories of a community torn apart. The town’s zip code was revoked by the U.S. Postal Service in 1992, a symbolic act that underscored its impending erasure.

What remained of Centralia quickly became a ghost town. Houses were demolished, stores boarded up, and streets became eerily silent. Nature began its reclamation project, with weeds sprouting through cracked pavement and trees growing wild in what were once manicured lawns. The only structures left standing were the St. Ignatius Cemetery, a poignant reminder of lives lived and lost, and a handful of private homes belonging to the few residents who refused to leave.

These holdouts, a small but fiercely determined group, fought tirelessly to retain their properties. They argued that the fire was not as widespread or dangerous as authorities claimed, or that the government simply hadn’t tried hard enough to extinguish it. Their struggle became a symbol of individual defiance against bureaucratic decree. In 2013, after decades of legal battles, the remaining residents – by then only a handful of families – reached an agreement with the state, allowing them to live out their lives on their properties, but ownership would revert to the state upon their deaths. It was a pyrrhic victory, allowing them to stay, but ensuring the town’s ultimate demise.

Today, Centralia is a macabre tourist attraction, drawing urban explorers, photographers, and those fascinated by its unique, unsettling story. For years, one of its most iconic features was "Graffiti Highway," a mile-long stretch of abandoned Route 61 that had been closed due to severe cracking and buckling caused by the fire. Artists and visitors covered the asphalt in layers of colorful graffiti, transforming it into an ever-evolving outdoor art gallery and a stark visual metaphor for the town’s vibrant, if chaotic, resilience. However, in 2020, the property owner, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, covered the highway with earth, citing safety concerns and environmental damage from excessive visitors, erasing another tangible piece of Centralia’s peculiar legacy.

Yet, even without Graffiti Highway, the allure of Centralia persists. Smoke still rises from numerous vents and fissures, particularly on cold days, creating an otherworldly landscape. The air still carries that tell-tale sulfuric tang. The ground, in places, remains dangerously hot. Scientists estimate that the coal seam fire, which stretches for miles beneath the surface, contains enough fuel to burn for another 250 years or more. It is an unquenchable inferno, a geological phenomenon that dwarfs human attempts at control.

Centralia’s story is more than just a tale of a town consumed by fire; it is a cautionary parable about the unintended consequences of human action, the limits of our ability to control natural forces, and the heartbreaking cost of environmental neglect. It speaks to the resilience of a community fighting for its existence, the complex interplay between individual rights and public safety, and the eerie beauty that can emerge from devastation. As the smoke continues to rise from the forgotten streets of Centralia, it serves as a silent, smoldering monument to a past that refuses to be extinguished, a ghost town that breathes fire, forever etched into the landscape of Pennsylvania and the collective imagination.