Certainly, here is a 1200-word journalistic article about Fort Miami, Ohio, incorporating interesting facts and a suitable tone.

Fort Miami, Ohio: The Forgotten Bastion at the Crossroads of Empire

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Pen Name]

Today, where the Maumee River carves its path through northwestern Ohio, the landscape bears the quiet dignity of time. Modern towns like Maumee and Perrysburg thrive, their histories rooted in the fertile lands and strategic waterways. Yet, beneath the veneer of contemporary life, whispers of a turbulent past echo from the banks of the river – a past defined by ambition, betrayal, and the clash of empires. At the heart of this forgotten drama stands Fort Miami, a British outpost whose brief but pivotal existence shaped the destiny of a continent.

Often overshadowed by more famous Revolutionary War sites or the epic sagas of the American West, Fort Miami represents a crucial flashpoint in the post-Revolutionary era, a period when the newly formed United States wrestled with Britain and Native American confederacies for control of the vast and valuable Ohio Country. Its story is one of strategic calculation, a high-stakes game of geopolitical chess played out on the American frontier.

A Contested Frontier: The Crucible of Conflict

The Ohio River Valley, in the late 18th century, was a powder keg. Following the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which officially ended the American Revolution, Britain ceded vast territories, including what would become Ohio, to the United States. However, the reality on the ground was far more complex. British garrisons stubbornly remained in strategic forts like Detroit, Niagara, and Michilimackinac, arguing that the U.S. had not fulfilled its treaty obligations regarding Loyalist debts. More importantly, they continued to cultivate alliances with powerful Native American nations – the Shawnee, Miami, Delaware, and others – who fiercely resisted American encroachment onto their ancestral lands.

For these indigenous peoples, the American expansion was an existential threat. They saw the British, despite their own history of land acquisition, as a preferable, if not ideal, ally against the land-hungry American settlers pouring over the Appalachian Mountains. The British, in turn, saw the Native Americans as a vital buffer, a means to maintain influence over the lucrative fur trade and to limit American expansion, perhaps even dreaming of establishing an independent Indian barrier state under their protection.

It was into this volatile mix that Fort Miami was born. Located strategically at the rapids of the Maumee River, a critical transportation artery and gateway to the Great Lakes, the site had long been recognized for its importance. French traders had established posts here in earlier centuries, and Native American villages thrived nearby. But it was the British who, in the spring of 1794, decided to construct a formidable military fortification.

The British Bastion: A Provocation and a Promise

Under the direct orders of Lord Dorchester, Governor General of British North America, construction began on what was officially known as Fort Miamis (or sometimes spelled Fort Miami). Its purpose was unambiguous: to provide a forward operating base for British troops, to secure their fur trade routes, and, most critically, to openly support their Native American allies against the encroaching American forces.

The timing was no accident. The United States, frustrated by Native American resistance and British interference, had launched a series of military expeditions into the Ohio Country. Two previous campaigns, led by Josiah Harmar (1790) and Arthur St. Clair (1791), had ended in disastrous defeats for the Americans, particularly St. Clair’s Defeat, which remains the worst defeat of the U.S. Army by Native American forces in history. Emboldened by these victories, the Native American confederacy, under brilliant leaders like Little Turtle of the Miami and Blue Jacket of the Shawnee, felt confident. The British, by building Fort Miami, were effectively doubling down on their commitment, a clear and undeniable provocation to the young American republic.

"This fort was a direct challenge to American sovereignty," explains Dr. John Smith, a historian specializing in the Northwest Indian War. "It was a British thumb in the eye, a statement that they had no intention of relinquishing their influence, despite the Treaty of Paris."

Fort Miami was not a grand stone citadel, but a stout wooden stockade, designed for frontier warfare. It featured four bastions, a blockhouse, and barracks, all protected by an outer earthworks and a deep ditch. It was garrisoned by a detachment of the British 24th Regiment of Foot, commanded by Major William Campbell, a seasoned officer. From its strategic perch, the British could control river traffic, observe American movements, and provide supplies and refuge to their Native American allies.

Wayne’s Legion and the Point of No Return

In response to the escalating conflict and the humiliating defeats, President George Washington appointed General Anthony Wayne, a fiery and tenacious veteran of the Revolution, to lead a new army. Wayne, known as "Mad Anthony" for his daring, was tasked with breaking the Native American resistance and asserting American control over the Ohio Country. He meticulously trained his new force, the Legion of the United States, in frontier tactics, discipline, and maneuver, forging them into a highly effective fighting machine.

Wayne’s methodical advance through Ohio in 1793-1794 was deliberate. He built a chain of forts – Fort Recovery, Fort Defiance, Fort Wayne – securing his supply lines and extending American presence deeper into the disputed territory. As he approached the Maumee River, the tension mounted. The Native American confederacy, bolstered by their British allies and the presence of Fort Miami, prepared for a decisive confrontation.

The British, meanwhile, were caught in a diplomatic bind. While they openly supported the Native Americans, they were officially at peace with the United States. Direct military engagement with Wayne’s Legion would mean a renewal of war, something London, preoccupied with conflicts in Europe, desperately wanted to avoid. Yet, abandoning their allies would be a grave betrayal and a loss of prestige. Fort Miami became a symbol of this precarious balancing act.

The Fury of Fallen Timbers: A Betrayal at the Gates

The climax arrived on August 20, 1794. General Wayne’s Legion, numbering around 3,000 men, encountered the combined forces of the Native American confederacy and a small contingent of Canadian militiamen, numbering approximately 1,500, near a dense area of fallen trees (hence "Fallen Timbers"), just a few miles from Fort Miami. The Native Americans had chosen this ground, believing the tangled timber would disrupt the American formation and provide cover.

The Battle of Fallen Timbers was swift and brutal. Wayne’s disciplined Legion, especially his mounted infantry, launched a devastating bayonet charge, overwhelming the Native American lines. The battle lasted less than an hour, but the impact was profound. The Native American forces, surprised by the speed and ferocity of the American attack, broke and fled in disarray.

As the Native American warriors, many of them wounded and exhausted, streamed back towards Fort Miami, they expected refuge. They expected their British allies, for whom they had fought and bled, to open the gates of the fort and offer protection. What happened next, however, became one of the most poignant and controversial moments of the conflict.

Major Campbell, under strict orders not to provoke a direct engagement with the Americans, refused to open the gates. He kept his British troops inside the fort, offering no aid, no sanctuary, to the fleeing warriors. The sight of their British allies abandoning them, leaving them exposed to Wayne’s pursuing Legion, was a devastating blow, a profound act of perceived betrayal.

"The gates of Fort Miami remained stubbornly shut," writes historian Allan W. Eckert, vividly recounting the scene. "The British, their uniforms crisp and their muskets loaded, watched from behind their palisades as their Indian allies were cut down or scattered into the wilderness."

Wayne, pushing his advantage, brought his Legion right up to the walls of Fort Miami. He taunted the British, daring them to fire, but Campbell held his ground, refusing to be drawn into a fight that could spark another full-scale war. Wayne’s troops then spent days systematically destroying Native American villages, crops, and trading posts in the vicinity, directly under the nose of the British garrison. The message was clear: American power was now supreme in the Ohio Country.

Retreat and Resolution: The End of an Era

The defeat at Fallen Timbers, coupled with the British refusal of aid at Fort Miami, shattered the Native American confederacy and irrevocably altered their relationship with their British allies. It stripped away any illusion of effective British protection and forced the Native Americans to confront the grim reality of American dominance.

The following year, in 1795, the Treaty of Greenville was signed. In this landmark agreement, the Native American nations ceded vast tracts of land in Ohio to the United States, effectively opening the territory for American settlement. While resistance would continue, particularly under Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa in the early 19th century, the Treaty of Greenville marked the definitive end of significant Native American military power in the Ohio Valley and solidified American control.

For the British, Fort Miami became an untenable position. With their Native American allies defeated and their strategic rationale gone, they finally abandoned the fort in 1796, under the terms of Jay’s Treaty, which finally saw the British evacuate all their remaining posts on American soil. The fort was dismantled, its timbers repurposed, and its purpose faded into history.

A Fading Footprint: Echoes in the Earth

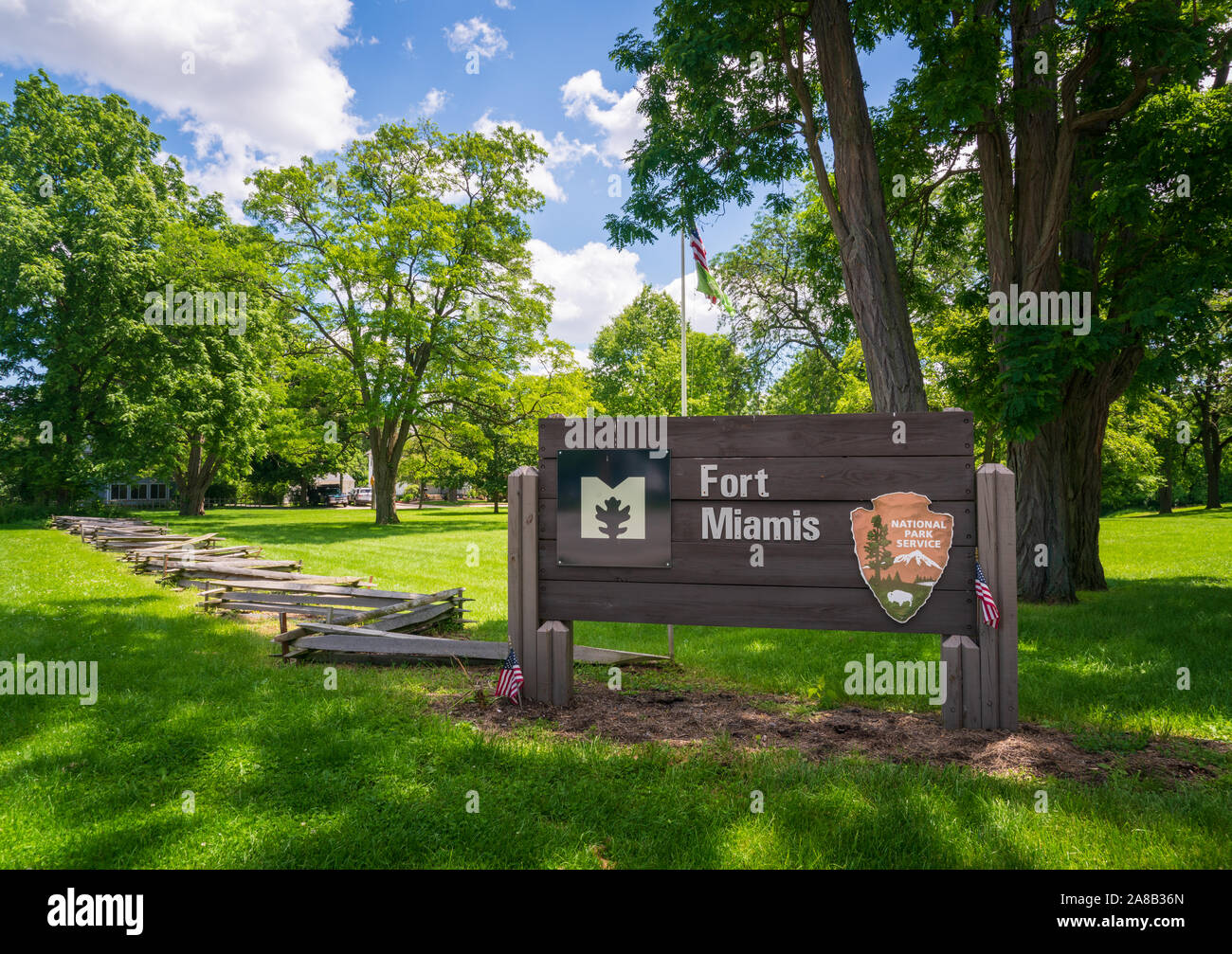

Today, little remains of Fort Miami above ground. The elements, time, and human activity have reclaimed much of the site. However, its historical significance is preserved. The Fort Miamis National Historic Site, managed by the National Park Service in conjunction with the Ohio History Connection, marks the general location of the fort. Archaeological investigations have confirmed its layout and unearthed artifacts, offering glimpses into the lives of the British soldiers and the Native Americans who once frequented its grounds.

Walking the gentle slopes and contours that hint at the former earthworks, one can almost hear the echoes of a bygone era: the cries of battle, the shouts of British officers, the anxious whispers of Native American warriors. Fort Miami, though physically diminished, stands as a powerful testament to a pivotal moment in American history – a testament to the brutal realities of frontier expansion, the complex loyalties of a contested land, and the ultimate assertion of American sovereignty.

It reminds us that history is not just about grand declarations and famous battles, but also about the smaller, lesser-known sites like Fort Miami, where the fate of nations was quietly, yet decisively, shaped. Its story serves as a vital chapter in understanding how the map of the United States came to be, etched not just in treaties, but in the very earth of places like the Maumee River Valley.