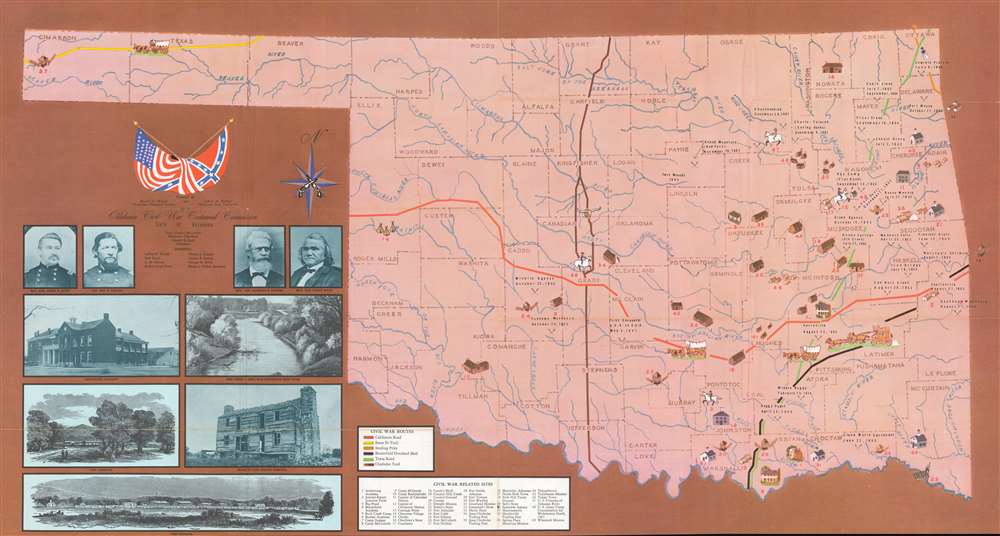

Certainly! Here is a 1200-word journalistic article about Oklahoma Civil War battles, focusing on their unique aspects and historical significance.

The Crucible of Indian Territory: Oklahoma’s Overlooked Civil War

When one thinks of the American Civil War, images of Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Antietam often come to mind – battlefields etched into the national consciousness. Yet, far to the west, in what was then known as Indian Territory – present-day Oklahoma – a conflict of equally brutal intensity, unique complexities, and profound consequences unfolded. This often-overlooked theater of war was a crucible where Native American nations, already displaced and struggling for sovereignty, were torn apart by divided loyalties, economic pressures, and the raw violence of a nation at war with itself.

The story of the Civil War in Indian Territory is not merely a footnote; it is a vital chapter marked by some of the most diverse fighting forces, prolonged guerrilla warfare, and a level of devastation that arguably surpassed that seen in many other regions. It was a war where brother fought brother, not just within the broader American context, but often within the same tribal families.

A Powder Keg of Divided Loyalties

The seeds of conflict in Indian Territory were sown long before Fort Sumter. Following their forced removal from the southeastern United States during the infamous "Trail of Tears" in the 1830s, the Five Civilized Tribes – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – had re-established themselves in the lands designated for them. However, their new homes were not free from the national schism. Many of these nations, particularly the Choctaw and Chickasaw, had adopted Southern institutions, including chattel slavery, and their economies were deeply intertwined with the Southern states. Culturally and economically, they felt a closer affinity to the Confederacy.

Conversely, other factions within these tribes, particularly among the Creek and Seminole, held strong Union sympathies, often rooted in traditional ways of life and a distrust of the Southern-leaning mixed-blood elites who controlled tribal governments. When federal troops withdrew from Indian Territory garrisons at the war’s outset, it created a power vacuum that the Confederacy, eager to secure its western flank and recruit new allies, swiftly moved to fill.

Confederate Commissioner Albert Pike, dispatched by Jefferson Davis, negotiated treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes, promising protection and recognition of their sovereignty in exchange for military support. These treaties, signed in 1861, formally brought most of the tribal governments into alliance with the Confederacy, though significant segments of their populations remained fiercely loyal to the Union.

The Flight of the Loyal Refugees: Opothleyahola’s Odyssey

One of the most compelling narratives of the early war in Indian Territory centers on Opothleyahola, a revered traditionalist and chief of the Upper Creeks. Resolutely pro-Union, he refused to acknowledge the Confederate treaties. As Confederate influence grew, Opothleyahola organized a mass exodus of loyal Creeks, Seminoles, and a smattering of Cherokees and Chickasaws, along with African American slaves and freedmen, numbering in the thousands. His goal: to reach the Union lines in Kansas, a desperate trek for survival.

This "Trail of Blood on Ice," as some historians have termed it, became a grim test of endurance and courage, punctuated by several brutal skirmishes. Confederate forces, led by Colonel Douglas H. Cooper and including Stand Watie’s newly formed Cherokee Mounted Rifles, pursued Opothleyahola’s column relentlessly.

The first significant engagement was the Battle of Round Mountain on November 19, 1861, near present-day Yale, Oklahoma. Opothleyahola’s forces, though poorly armed, skillfully ambushed Cooper’s Confederates before retreating further north.

A month later, on December 9, 1861, the Battle of Chusto-Talasah (also known as Caving Banks or Shoal Creek) occurred near present-day Sperry. Opothleyahola’s warriors again managed to hold off their pursuers, inflicting casualties before continuing their harrowing journey.

The final, devastating confrontation came on December 26, 1861, at the Battle of Chustenahlah, near the Arkansas River in what is now Osage County. Outnumbered and outgunned, Opothleyahola’s forces were overwhelmed. The Union loyalists suffered heavy casualties, and many perished from exposure and starvation during the final desperate push to Kansas. This tragic flight highlighted the deep internal divisions within the tribes and the merciless nature of the war that had come to their lands.

Stand Watie: The Last Confederate General

The war in Indian Territory produced one of the Confederacy’s most formidable and enduring figures: Stand Watie, a mixed-blood Cherokee and signer of the Treaty of New Echota (which led to the Trail of Tears). A brilliant guerrilla leader and cavalry commander, Watie rose to the rank of Brigadier General – the only Native American to achieve this distinction in the Confederacy. His Cherokee Mounted Rifles became legendary for their daring raids, resilience, and effectiveness.

Watie’s troops participated in the pivotal Battle of Pea Ridge (Elkhorn Tavern) in Arkansas in March 1862, fighting alongside Confederate regulars and demonstrating their fierce combat prowess. Though a tactical Union victory, the battle showcased the significant role Indian Territory troops would play in the broader trans-Mississippi theater.

Honey Springs: The "Gettysburg of the West"

The most decisive and largest battle fought in Indian Territory was the Battle of Honey Springs on July 17, 1863, near present-day Checotah. Often referred to as the "Gettysburg of the West," this engagement was a turning point for Union control of the region.

Union forces, commanded by Major General James G. Blunt, consisted of approximately 3,000 soldiers, a remarkably diverse fighting force that included white, Native American (Creek, Cherokee, and Osage), and African American regiments. Notably, the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry played a pivotal role, proving their mettle and courage in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Their performance here helped shatter prevalent racial stereotypes about the combat capabilities of African American soldiers.

Confederate forces, numbering around 6,000, were led by Douglas H. Cooper and included regiments from Texas, Arkansas, and the various Native American nations, including Stand Watie’s command. The battle unfolded in the searing summer heat and humidity, with troops slogging through muddy terrain after recent rains.

The fighting was intense and brutal. The Union advance was met with determined Confederate resistance, but superior Union artillery and the fierce charges of the 1st Kansas Colored and other regiments ultimately broke the Confederate lines. The Confederates were routed, retreating in disarray and leaving behind vital supplies and equipment.

Honey Springs was a resounding Union victory. It secured Union control of the Arkansas River, a crucial supply artery, and effectively crippled Confederate efforts to regain significant ground in Indian Territory. While the war would continue, the battle shifted the strategic initiative decisively to the Union side in the region.

The Long Shadow of Guerrilla Warfare

Even after Honey Springs, the conflict in Indian Territory did not cease; it merely transformed. The region became a hotbed of guerrilla warfare, raids, and skirmishes, characterized by intense foraging, bushwhacking, and a complete breakdown of civil order. Both sides resorted to scorched-earth tactics, leaving the land and its people utterly devastated.

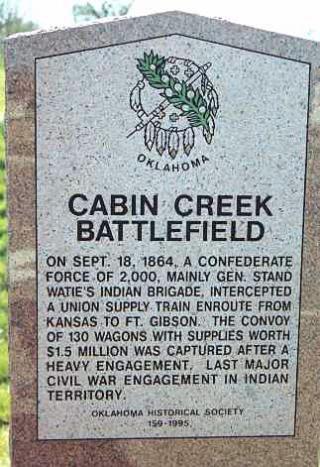

The First Battle of Cabin Creek on July 1, 1863, just weeks before Honey Springs, saw Union forces successfully escort a vital supply train through Confederate territory, securing the route for future operations. However, Stand Watie, ever resourceful, demonstrated his enduring threat in the Second Battle of Cabin Creek on September 19, 1864. In a masterstroke of ambush tactics, Watie’s Cherokees, Creek, and Seminole troops successfully attacked a large Union supply train and its escort. This was Watie’s greatest independent victory, capturing over 100 wagons, 700 mules, and significant quantities of supplies, providing a much-needed boost to the struggling Confederate war effort in the trans-Mississippi.

These raids, coupled with continuous small-scale skirmishes, ensured that no part of Indian Territory was truly safe. Farms were burned, livestock stolen, and families displaced. The suffering of the civilian population, caught between warring factions and internal tribal feuds, was immense. Thousands became refugees, enduring starvation and disease.

The War’s End and a Devastating Legacy

As the war drew to a close across the nation, Stand Watie remained defiant. He continued his operations until June 23, 1865, when he formally surrendered his command at Doaksville, near Fort Towson in the Choctaw Nation. He was the very last Confederate general to surrender his forces, a testament to his tenacity and the protracted nature of the conflict in Indian Territory.

The aftermath of the Civil War for the Native American nations was catastrophic. Despite the fact that many tribal members had fought for the Union, and some tribes had been deeply divided, the U.S. government treated all Five Civilized Tribes as if they had been disloyal to the Union. New treaties were imposed in 1866, forcing the tribes to cede vast tracts of their land for the resettlement of other tribes and for the construction of railroads – a precursor to the eventual dissolution of tribal lands and the opening of Oklahoma to white settlement.

The war decimated the population, destroyed infrastructure, and exacerbated pre-existing tribal divisions. It fundamentally altered the political and social landscape of Indian Territory, setting the stage for its eventual transformation into the State of Oklahoma.

The Civil War in Indian Territory is a poignant reminder of the conflict’s far-reaching and deeply personal toll. It tells a story of survival, betrayal, and resilience, featuring unique military strategies, diverse combatants, and a level of devastation that echoes to this day. It is a vital chapter in American history that deserves to be remembered, studied, and understood for its profound impact on the Native American nations and the shaping of the American West.