Certainly! Here is a 1,200-word journalistic article about the Potawatomi Tribe.

Keepers of the Fire: The Enduring Spirit of the Potawatomi Nation

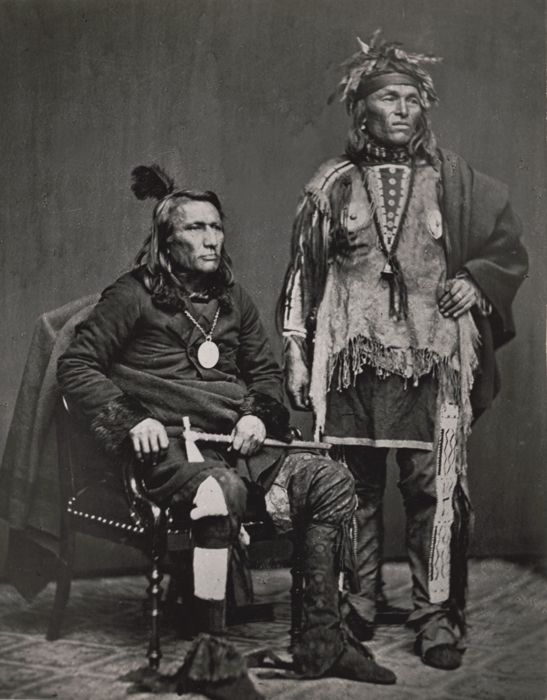

In the heart of North America, stretching from the Great Lakes across the plains, lies a story of profound resilience, deep cultural heritage, and an unwavering spirit. This is the story of the Potawatomi, the "Keepers of the Fire," a name that speaks volumes about their historical role, their spiritual connection, and their enduring flame of identity. From their ancient origins as part of the Anishinaabe confederacy to their contemporary status as vibrant, sovereign nations, the Potawatomi journey is a testament to survival against immense odds and a powerful example of cultural revitalization in the modern world.

The Potawatomi, or Bodéwadmi as they call themselves, are one of the three tribes of the Council of Three Fires (Niswi-mishkodewin), an enduring alliance with the Ojibwe (Keepers of the Faith) and Odawa (Keepers of the Trade). Their name, often translated as "Keepers of the Fire," refers to their historical role as the central fire of this confederacy, symbolizing their responsibility for maintaining the spiritual and cultural heart of the alliance. Originally inhabiting lands around Lake Michigan, particularly in what is now Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana, the Potawatomi were a semi-nomadic people, moving with the seasons to hunt, fish, gather, and cultivate crops like corn, beans, and squash.

Their traditional life was rich with ceremony, guided by the Seven Grandfather Teachings – wisdom, love, respect, bravery, honesty, humility, and truth – principles that continue to inform their governance and community values today. Family and clan systems provided social structure, while skilled artisans produced intricate beadwork, pottery, and birchbark canoes that were vital for their economy and travel across the vast waterways of their territory.

The arrival of Europeans in the 17th century brought profound changes. Initially, the Potawatomi engaged in trade, forging strong alliances with the French, particularly in the lucrative fur trade. Their strategic location made them key players in colonial conflicts, often siding with the French against the British, and later with the British against the nascent United States. However, these alliances also exposed them to European diseases, which decimated their populations, and gradually drew them into a global economic system that began to undermine their traditional ways of life.

The 19th century ushered in the darkest chapter of Potawatomi history: the era of forced removal. As American settlers pushed westward, the U.S. government implemented policies aimed at dispossessing Native nations of their lands. Through a series of coercive treaties, often signed under duress or by unrepresentative factions, the Potawatomi ceded millions of acres. The most infamous event was the "Potawatomi Trail of Death" in 1838. Under armed guard, 859 Potawatomi people were forcibly marched over 660 miles from their homes in northern Indiana to new lands in Kansas. The journey, lasting two months, claimed the lives of over 40 people, mostly children and elders, due to disease, starvation, and exhaustion.

"The Trail of Death is not just a historical event; it’s a wound that continues to reverberate through generations," stated a contemporary Potawatomi elder. "It speaks to the immense suffering our ancestors endured, but also to their incredible will to survive, to carry our culture forward no matter the cost."

This forced migration scattered the Potawatomi people, leading to the formation of distinct communities in different geographical areas. Today, there are federally recognized Potawatomi nations in Michigan, Wisconsin, Kansas, Oklahoma, and even Canada (where they are known as First Nations). Each community, while sharing a common heritage, has developed its unique trajectory and adaptations since the removal era.

Despite the trauma of removal and subsequent policies aimed at assimilation, such as boarding schools designed to strip children of their language and culture, the Potawatomi never lost their identity. The mid-20th century saw a renewed push for self-determination. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 allowed many tribes to establish constitutional governments, laying the groundwork for greater sovereignty. However, the subsequent "Termination Era" of the 1950s and 60s, which sought to end the federal government’s trust relationship with tribes, threatened to erase their unique status. The Potawatomi, like many other tribes, fought fiercely against termination, advocating for their inherent rights to self-governance.

In recent decades, the Potawatomi nations have experienced a powerful resurgence, marked by significant economic development, cultural revitalization, and the assertion of their inherent sovereignty. A key driver for many has been gaming, with several Potawatomi bands successfully establishing casinos. This revenue has been transformative, allowing nations to invest in their communities in unprecedented ways.

"Gaming is not just about entertainment; it’s about economic sovereignty," explained a leader from one of the Potawatomi nations in Oklahoma. "It allows us to build schools, health clinics, housing, and infrastructure that our people need and deserve. It means we’re no longer dependent on federal handouts, but can chart our own course and create opportunities for our future generations."

Beyond economic ventures, a profound commitment to cultural preservation and language revitalization is at the heart of the modern Potawatomi experience. The Potawatomi language, Neshnabemwin, is critically endangered, but dedicated efforts are underway across various communities to bring it back from the brink. Immersion schools, language camps, and online resources are teaching a new generation to speak the language of their ancestors.

"Our language is the heartbeat of our culture," observed a language instructor at a Potawatomi cultural center in Michigan. "When we speak Neshnabemwin, we’re not just speaking words; we’re speaking the wisdom, humor, and history of thousands of years. It connects us directly to our ancestors and ensures our unique worldview continues."

Traditional arts, ceremonies, and storytelling are also experiencing a revival. Powwows, sweat lodges, naming ceremonies, and other cultural practices are being taught and celebrated with renewed vigor. Younger generations are actively engaging with their heritage, learning traditional crafts like basket weaving, ribbonwork, and drumming, and participating in ceremonies that reinforce their identity and connection to the land.

Furthermore, Potawatomi nations are actively engaged in environmental stewardship and land management, reflecting their deep traditional respect for the Earth. They are involved in conservation efforts, sustainable resource management, and protecting ancestral lands and waters for future generations. Many also offer comprehensive social services, including elder care, youth programs, and educational scholarships, demonstrating their commitment to the well-being of their citizens.

The diverse Potawatomi nations of today, while distinct in their governance and local initiatives, share a common thread: an enduring commitment to the "Keepers of the Fire" legacy. This means safeguarding their cultural flame, nurturing their language, and ensuring the continued prosperity and sovereignty of their people. From the bustling enterprises of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation in Oklahoma to the strong cultural programs of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi in Michigan, and the vibrant communities of the Forest County Potawatomi in Wisconsin, their collective story is one of a people who have faced unimaginable challenges and emerged stronger, their fire burning brighter than ever.

The Potawatomi journey is a living narrative, continually unfolding. It serves as a powerful reminder that Indigenous cultures are not relics of the past but dynamic, evolving forces that continue to shape the fabric of North America. As the Keepers of the Fire look to the future, they do so with the wisdom of their ancestors, the strength of their present communities, and an unwavering determination to ensure their sacred fire continues to burn brightly for generations to come. Their story is a beacon of hope, resilience, and the enduring power of cultural identity.