The Stone Age’s Last Stand: Unearthing the Legacy of Bedrock City, South Dakota

CUSTER, South Dakota – In the rugged embrace of the Black Hills, where granite formations pierce the sky and pine forests whisper ancient tales, once stood a different kind of antiquity. Not the geological wonders carved by eons, but a vibrant, albeit crumbling, homage to a prehistoric fantasy: Bedrock City. For over half a century, this roadside attraction near Custer, South Dakota, served as a vibrant, cartoonish portal to the Stone Age, drawing generations of families into the whimsical world of Fred Flintstone and his pals. Today, the echoes of “Yabba Dabba Doo!” are largely silent, replaced by the quiet hum of memory and the stark reality of demolition, leaving behind a poignant narrative of nostalgia, changing tastes, and the transient nature of even the most stubbornly “stone” attractions.

Opened in 1966, Bedrock City was more than just a theme park; it was a cultural artifact, a physical manifestation of Hanna-Barbera’s immensely popular animated series, The Flintstones. At a time when television was cementing its place in American homes and the interstate highway system was opening up the country to unprecedented levels of tourism, Bedrock City capitalized on a craving for family-friendly, recognizable entertainment. Its location was strategic, just a stone’s throw from national treasures like Mount Rushmore and Custer State Park, ensuring a steady stream of curious travelers.

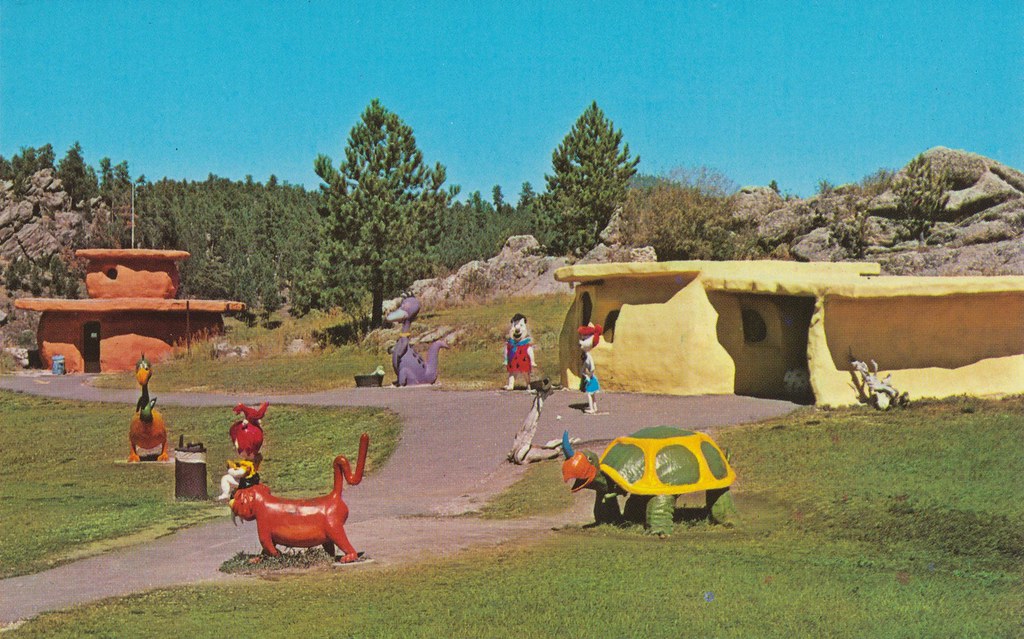

The vision for Bedrock City was born from the imagination of Francis and Linda Speckels, who, after securing a licensing agreement from Hanna-Barbera, meticulously crafted a world out of cement, steel, and a generous splash of vibrant, cartoonish paint. They didn’t just build structures; they sculpted an experience. Visitors would drive through a towering rock archway, immediately stepping into a landscape where the familiar tropes of modern life were hilariously reinterpreted through a prehistoric lens.

The park’s centerpiece was Fred Flintstone’s iconic cave-house, complete with a boulder-sized television set, a dinosaur-skull mailbox, and a car that you had to power with your own two feet. Nearby stood Barney and Betty Rubble’s more modest dwelling, the bustling Bedrock Diner (serving Bronto Burgers, naturally), and a general store stocked with Flintstones memorabilia. Children delighted in sliding down the long, curving tail of a towering Brontosaurus, riding miniature train cars designed to look like prehistoric vehicles, and posing for photos with life-sized, if somewhat weather-beaten, statues of Fred, Wilma, Pebbles, Dino, and the whole gang.

“It was pure magic,” recalls Sarah Jenkins, 52, who visited Bedrock City with her family in the late 1970s. “Everything was so brightly colored and just like on TV. That Brontosaurus slide felt like it went on forever. It was a simpler time, and Bedrock City perfectly captured that innocent fun.” Indeed, for decades, the park thrived, a testament to the enduring appeal of The Flintstones and the unique charm of the American roadside attraction. It wasn’t about high-tech thrills or immersive virtual realities; it was about stepping into a beloved cartoon and embracing its low-fi, high-charm aesthetic.

However, the sands of time, much like the Black Hills’ erosion, began to take their toll. As the 21st century dawned, Bedrock City faced a confluence of challenges. The initial generation of Flintstones fans grew up, and while the show remained a classic, its immediate cultural omnipresence waned. Newer, flashier theme parks, with their multi-million dollar rides and sophisticated storytelling, raised the bar for family entertainment. Bedrock City, with its aging infrastructure and increasingly faded paint, began to look less like a vibrant fantasy and more like a charming, albeit slightly dilapidated, relic.

Maintenance became a constant battle against the elements and the wear and tear of thousands of visitors. The iconic Brontosaurus slide, once a beacon of joy, started showing cracks. The cement structures, while sturdy, required continuous upkeep. The Speckels family, who had poured their lives into the park, found themselves in an increasingly difficult position.

By 2015, the writing was on the wall. After nearly 50 years, Bedrock City was officially put up for sale. The asking price? A cool $2 million, which later dropped to $1.5 million. The news sent ripples of nostalgia across the internet, sparking a brief but intense wave of media attention. Headlines ranged from “Yabba Dabba Don’t Let It Die!” to “Could You Be The Next Fred Flintstone?” People reminisced about their visits, sharing faded photographs and fond memories. There was a collective hope that a new owner would emerge, someone with the vision and capital to restore Bedrock City to its former glory.

Linda Speckels, in interviews at the time, expressed a wistful longing for the park to continue its legacy. “We had so many good times,” she told reporters, “but it’s time for someone else to take over. We just want to see it go to a good home.” The prospect of inheriting a piece of Americana, a fully-built theme park with decades of history, was certainly unique. But the challenges were equally formidable: the cost of renovation, the specialized maintenance, and the need to somehow reinvent or re-market a mid-century concept for a modern audience.

After a period of uncertainty, a buyer finally emerged in 2015-2016: the Schwartz family, owners of the nearby Reptile Gardens, another long-standing and beloved Black Hills attraction. Initial hopes soared. Perhaps the Schwartzes, with their proven track record in tourism, would breathe new life into Bedrock City, integrating it into the broader Black Hills experience.

However, the reality proved more complex. The Schwartzes had a different vision. While they appreciated the historical significance, the cost and effort to bring Bedrock City up to modern safety and entertainment standards, while simultaneously competing with their highly successful Reptile Gardens, was simply too great. The land, strategically located, held more value for other purposes.

And so, the demolition began. The iconic structures were systematically dismantled. Fred’s house, the Brontosaurus slide, the diner – one by one, the physical manifestations of the Stone Age fantasy vanished. The decision, while pragmatic, was met with a bittersweet sadness by many who had cherished their memories of the park. It marked the definitive end of an era, not just for Bedrock City, but for a certain type of unpretentious, character-driven roadside attraction that once dotted the American landscape.

Today, the site of Bedrock City is undergoing transformation. Some of the land has been repurposed, and while whispers of future developments linger, the vibrant, cartoonish world of the Flintstones is gone. A small, poignant reminder remains: the Bedrock City sign, or at least a version of it, still stands, a silent sentinel to what once was. Photographs, old home videos, and countless personal anecdotes are now the primary keepers of its flame.

The story of Bedrock City, South Dakota, is more than just the tale of a theme park’s rise and fall. It’s a microcosm of the changing face of American tourism and entertainment. It speaks to the enduring power of nostalgia, the challenges of maintaining aging infrastructure, and the constant evolution of what captures the public’s imagination. It reminds us that even the most “rock solid” institutions can be swept away by the currents of time.

As the sun sets over the Black Hills, casting long shadows across the landscape where Fred and Barney once roamed, one can almost hear a faint, distant echo of “Yabba Dabba Doo!” It’s a sound that now belongs to memory, a cherished chapter in the quirky, vibrant history of the American roadside. Bedrock City may be gone, but its spirit, like a fossil preserved in amber, continues to remind us of a time when imagination, a few bags of cement, and a beloved cartoon could create a truly unforgettable world.