Certainly, here is an article about John Wesley Powell, written in a journalistic style and approximately 1200 words in length.

The One-Armed Prophet of the Canyons: John Wesley Powell’s Enduring Legacy

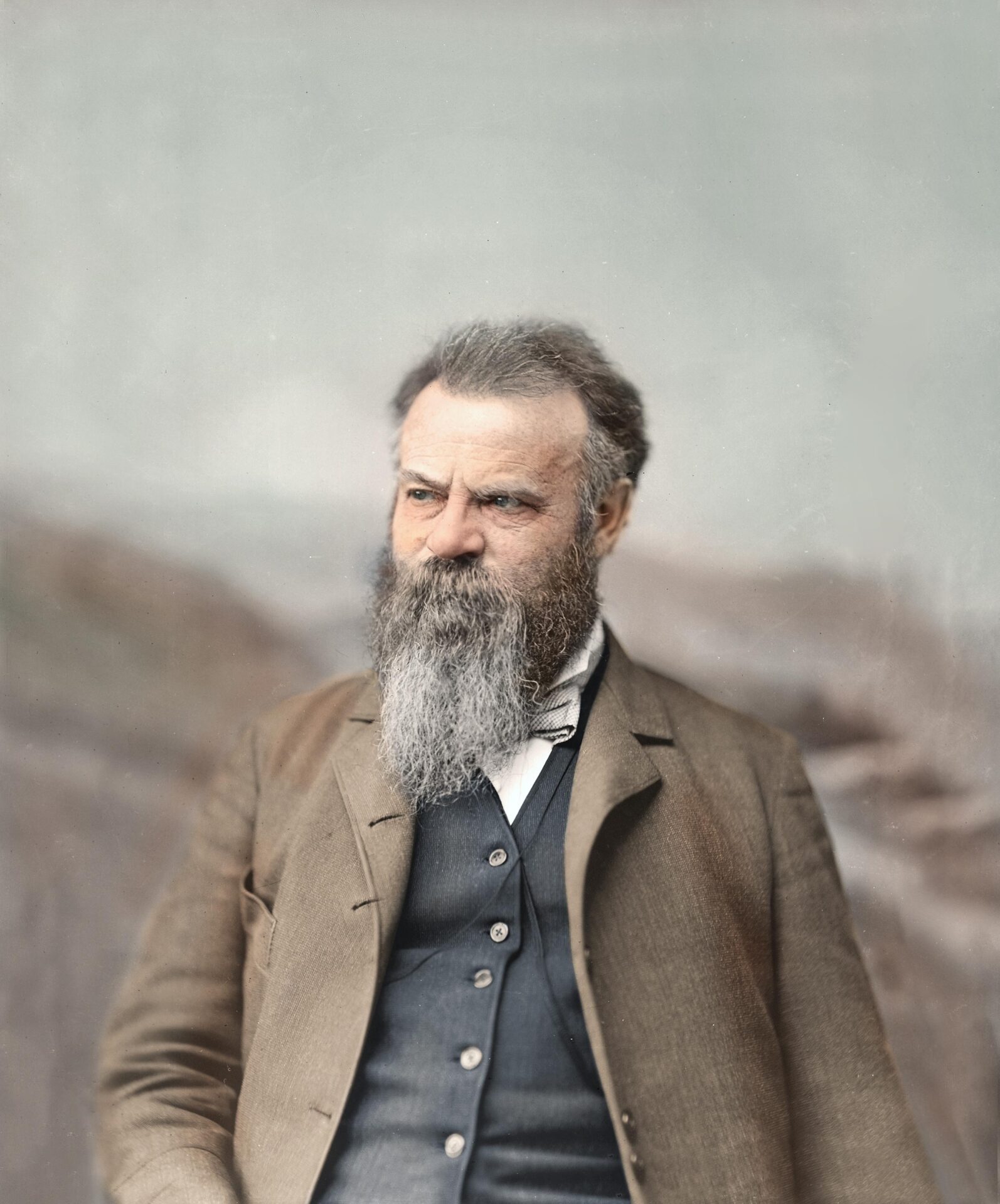

The American West, a land of myth and boundless horizon, owes much of its understanding not to a swashbuckling cowboy or a gold prospector, but to a quiet, one-armed Civil War veteran with an insatiable scientific curiosity: John Wesley Powell. His name, often overshadowed by the sheer scale of the landscapes he explored, represents a pivotal turning point in America’s relationship with its vast, untamed territories. He was not merely an adventurer; he was a scientist, an ethnologist, a cartographer, and ultimately, a prophet whose warnings about water scarcity echo with chilling relevance today.

Born in 1834 in New York, Powell’s early life was marked by a restless intellectual hunger. He pursued self-education with fervor, developing a deep passion for natural history, geology, and ethnology. He collected specimens, observed landscapes, and cultivated a keen analytical mind that would define his future endeavors. But it was the crucible of the Civil War that forged the man who would confront the Grand Canyon. Enlisting in the Union Army, he rose through the ranks, eventually commanding an artillery battery. At the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, a minie ball shattered his right arm, necessitating an amputation. Most men would have seen this as a life-altering disability, a reason to retreat. For Powell, it was merely a hurdle, a testament to his extraordinary resolve. He returned to duty just months later, remarkably learning to command artillery with his left arm, demonstrating a resilience that would define his later, more famous expeditions.

After the war, Powell took up a professorship at Illinois Wesleyan University, but the call of the unexplored was too strong. The American West remained largely a mystery, particularly its most formidable features. The Colorado River, a lifeline carving its way through a vast, unmapped expanse, was one of the last great blank spaces on the map of the contiguous United States. Stories of terrifying rapids, impassable canyons, and mythical waterfalls abounded. No one, it was widely believed, could navigate its full length.

It was this challenge that beckoned Powell. In May 1869, with meager funding and a motley crew of nine men, four wooden boats – the Emma Dean, Kitty Clyde’s Sister, Maid of the Canyon, and Cañonita – and provisions for ten months, Powell embarked on an expedition that would forever etch his name into the annals of exploration. Their mission was audacious: to chart the entire course of the Green and Colorado Rivers through the formidable canyon lands, culminating in the Grand Canyon itself.

The journey was a relentless test of endurance, skill, and nerve. Rapids, previously unknown and unnamed, hurled their small craft against sheer rock walls. Food spoiled, equipment was lost, and the constant threat of capsizing or starvation loomed. Powell, often perched precariously on a rock to take scientific observations, directed his crew with a calm authority, despite his physical limitation. His journals, meticulously kept despite the hardships, vividly capture the awe and terror of the experience: "We have an unknown distance yet to run; an unknown river yet to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel, we know not; what walls rise over the river, we know not."

As weeks turned into months, the privations took their toll. One boat was smashed, supplies dwindled, and morale plummeted. By late August, after nearly 100 days on the river, the crew faced their greatest challenge: a series of immense, roaring rapids at what they believed was the very end of the Grand Canyon. Three men – O.G. Howland, Seneca Howland, and William Dunn – convinced that the rapids were impassable and that death was imminent, opted to abandon the expedition, climbing out of the canyon in a desperate bid for civilization. Tragically, they were never seen again, likely killed by Native Americans who mistook them for hostile prospectors. Powell and the remaining five men, against all odds, pressed on, running the final, terrifying rapids. Just a day later, on August 29, 1869, they emerged from the mouth of the Grand Canyon, having successfully completed the first recorded transit of the Colorado River through its most formidable section.

The expedition was a triumph, not just of survival, but of science. Powell had meticulously recorded geological formations, mapped the river’s course, and made significant observations about the region’s natural history. His reports, initially published in Scribner’s Monthly and later in a full government report, captivated the nation and cemented his reputation as a pioneering explorer.

But Powell was no mere thrill-seeker. He understood that true exploration was about more than just charting blank spaces. It was about understanding the land, its resources, and its inhabitants. This holistic vision led him to his second, more systematically organized expedition in 1871-72, equipped with better boats, photographic equipment, and a dedicated team of scientists. This journey yielded an even richer trove of data, forming the bedrock of his subsequent career.

Powell’s influence soon extended far beyond the river. Recognizing the need for a systematic approach to understanding the nation’s geology, he became the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in 1881. Under his leadership, the USGS transformed from a loose collection of regional surveys into a cohesive, scientific institution dedicated to mapping the vast resources of the American West. He initiated the comprehensive topographic mapping of the entire country, a monumental undertaking that continues to this day.

Concurrently, Powell’s deep respect for Native American cultures led him to establish and direct the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE) in 1879. He championed the scientific study of indigenous languages, customs, and histories, believing it crucial to record and understand these cultures before they vanished under the relentless tide of westward expansion. He collected thousands of artifacts, recorded oral histories, and published groundbreaking ethnological studies, fundamentally shaping the field of American anthropology.

Yet, perhaps Powell’s most prescient, and initially unheeded, contribution came from his understanding of the West’s fundamental limitation: water. His observations during his expeditions convinced him that the conventional wisdom guiding westward settlement – the "rain follows the plow" myth – was dangerously flawed. The vast majority of the West, he realized, was arid. In 1878, he published his seminal "Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, with a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah."

This report was revolutionary. Powell argued that traditional land policies, based on the humid East’s model of 160-acre homesteads, were utterly unsuited for the arid West. He proposed that settlement should be organized not by arbitrary square-mile sections, but by hydrological basins, with communities centered around reliable water sources. He advocated for collective, rather than individual, control over water, emphasizing that water, not land, was the limiting factor for development. "Water," he famously declared, "is the chief factor in the development of the West." He warned against the dangers of over-appropriation, predicting future conflicts and environmental degradation if his recommendations were ignored.

His ideas, however, clashed violently with the prevailing ethos of limitless expansion, individualistic enterprise, and the powerful interests of railroad companies and land speculators who stood to profit from unchecked development. Congress largely rejected his proposals, clinging to the belief that irrigation would simply make the deserts bloom and that nature would somehow conform to human desires. Powell’s warnings were dismissed as pessimistic, even unpatriotic. He was viewed as an obstacle to progress.

Despite the political battles and eventual decline in his administrative power (he resigned from the USGS in 1894 due to dwindling budgets and political opposition), Powell never wavered in his scientific integrity. He continued to advocate for rational resource management, understanding that the seemingly infinite West had finite limits. He died in 1902, his most profound insights about water still largely unheeded.

Today, more than a century later, Powell’s legacy resonates with profound clarity. The West grapples with chronic water shortages, interstate water disputes, and the consequences of over-development in arid regions, precisely as he predicted. The Colorado River, once a wild torrent, is now a highly controlled, over-allocated system struggling to meet the demands of millions. His vision of hydrological planning and collective water management, once dismissed, is now increasingly seen as the only sustainable path forward.

John Wesley Powell was more than an explorer who conquered a canyon. He was a pioneer who brought scientific rigor to a continent, a visionary who sought to understand the land on its own terms, and a prophet who dared to speak uncomfortable truths about the limits of nature. His one arm, lost in battle, became a symbol of his unwavering determination to confront the unknown, whether it was a raging river or the uncomfortable realities of a growing nation. In an era when the West faces unprecedented environmental challenges, the wisdom of the one-armed prophet of the canyons stands as a stark, enduring testament to the power of foresight and the enduring relevance of scientific understanding.