Echoes of the Plains: The Enduring Heart of Cheyenne Culture

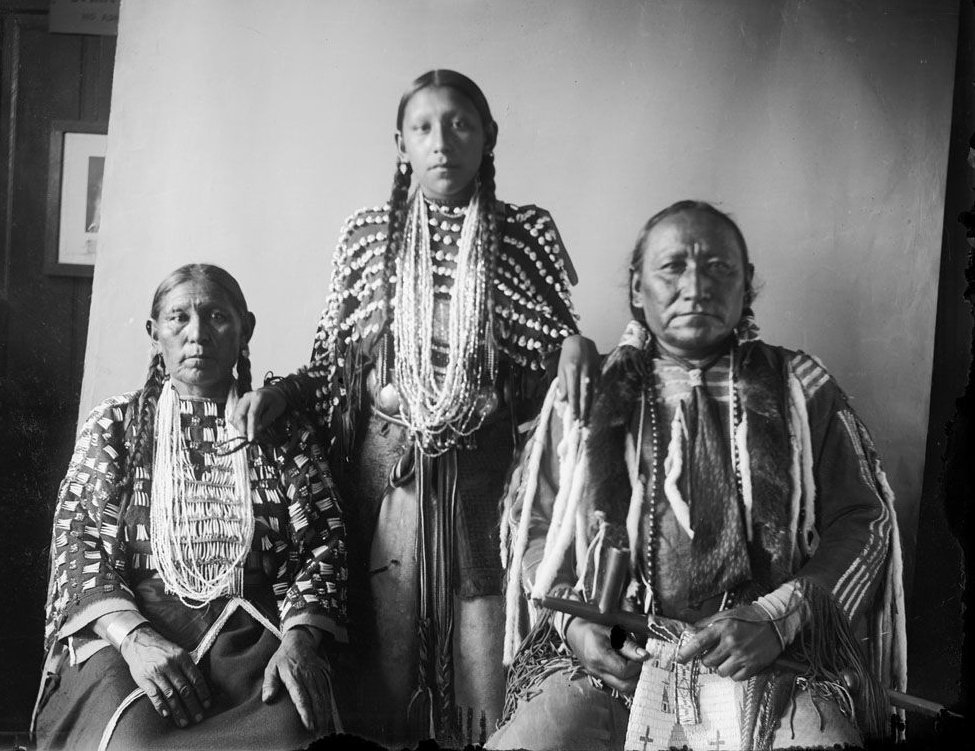

Beyond the sepia tones of historical photographs and the often-misrepresented narratives of the American West, lies a vibrant, living culture – that of the Cheyenne people. Known to themselves as Tsistsistas (The People), the Cheyenne have navigated centuries of profound change, from their nomadic existence on the Great Plains to forced relocation and the challenges of the modern era. Yet, through it all, their core cultural practices, steeped in spirituality, community, and an unbreakable connection to the land, have not only endured but continue to thrive, adapting and evolving with remarkable resilience.

To understand Cheyenne culture is to understand a worldview shaped by the vast expanse of the plains, the rhythm of the buffalo hunt, and an intricate spiritual relationship with the Creator, Ma’heo’o. It is a culture built on principles of respect, humility, generosity, and courage, passed down through generations not merely as traditions, but as essential ways of being.

The Spiritual Core: Ma’heo’o and the Sacred Path

At the heart of Cheyenne life is a deep, pervasive spirituality that permeates every aspect of existence. Ma’heo’o, the Great Spirit or Great Teacher, is not a distant deity but an ever-present force in the world, in nature, and within every living being. This belief fosters a profound reverence for all creation – the land, animals, plants, and fellow humans.

Central to Cheyenne spiritual practice is the understanding of sacred balance and interconnectedness. Ceremonies are not just rituals; they are vital acts of renewal, purification, and communion. Among the most profound is the Sun Dance (Tsėhesenėstsestōtse), a multifaceted ceremony of sacrifice, prayer, and renewal that serves as the spiritual anchor for the entire community. Held traditionally in late spring or early summer, it is a time for intense prayer, fasting, and physical hardship, often involving piercing as a form of personal sacrifice for the well-being of the people.

"The Sun Dance is not merely a ceremony; it is the heartbeat of our people, a profound act of sacrifice and renewal that connects us to Ma’heo’o and to each other," says John Spotted Tail, a Cheyenne elder and cultural keeper from the Northern Cheyenne Nation. "It reminds us that nothing truly great comes without giving something of ourselves, for the benefit of all." Participants, often young men and women, undergo rigorous preparation, guided by spiritual leaders, to offer their pain and endurance as a prayer for healing, prosperity, and the continuation of their way of life. It is a testament to the Cheyenne spirit that despite historical attempts to suppress it, the Sun Dance has persevered and remains a powerful unifying force today.

Another vital spiritual practice is the Vision Quest (Votive Offering), a solitary journey into nature, often to a remote, sacred place, undertaken by individuals seeking spiritual guidance, personal revelation, and a deeper connection with Ma’heo’o. Participants fast and pray for several days, hoping to receive a vision or message that will guide their path and purpose in life. This intensely personal experience is a cornerstone of individual spiritual development within the Cheyenne tradition.

The Sweat Lodge (Ma’hēo’o’s Teepee) also plays a crucial role in purification and prayer. A domed structure covered with blankets or hides, heated stones are placed inside, and water is poured over them to create steam. Participants enter to pray, sing, and cleanse themselves physically, mentally, and spiritually. It is considered a place of rebirth and reconnection with the natural world and the spirit realm.

The Fabric of Society: Kinship, Community, and Roles

Cheyenne society was traditionally organized into autonomous bands, each with its own leaders, but united by shared language, culture, and a council of chiefs who governed the entire nation. Kinship ties were paramount, extending far beyond the nuclear family to embrace a vast network of extended relatives. Children were raised not just by parents but by the entire community, instilling a strong sense of collective responsibility and belonging.

The Tipi (Nėstse), the traditional Cheyenne home, symbolizes this holistic worldview. More than just a shelter, the tipi was considered a miniature universe, with the poles representing the paths to the spiritual world and the circular base reflecting the continuous cycle of life. Its portability allowed the Cheyenne to follow the buffalo herds, which were central to their subsistence and economy. Every part of the buffalo was utilized – meat for food, hide for clothing and shelter, bones for tools, sinew for thread. This meticulous use reflected a profound respect for the animal and the resources provided by Ma’heo’o.

Within Cheyenne society, distinct roles contributed to the well-being of the whole. Men traditionally served as hunters, warriors, and protectors, while women were responsible for raising children, preparing food, crafting clothing, and maintaining the home. Both genders held positions of respect and influence, with women often playing significant roles in spiritual ceremonies and community decision-making. Warrior societies, such as the Dog Soldiers, were highly respected groups of men who not only protected the bands but also maintained order and discipline within the community.

The Power of Story: Oral Tradition and Language

For the Cheyenne, history, wisdom, and cultural values are primarily transmitted through oral tradition. Storytelling is not merely entertainment; it is a sacred act, a living library of knowledge passed down from elders to younger generations. Myths, legends, historical accounts, and moral lessons are woven into narratives that teach about the Cheyenne worldview, their relationship with the land, and the importance of ethical behavior.

"Our language, Tsėhesenėstsestotse, carries the very soul of our people, the nuances of our worldview, and the wisdom of our ancestors," explains Dr. Sarah Many Horses, a Cheyenne linguist. "It’s more than just words; it’s a way of thinking, a way of connecting to our past and envisioning our future." The Cheyenne language, part of the Algonquian family, is descriptive and rich, embodying concepts that are often difficult to translate directly into English. It reflects a deep understanding of the natural world and the interconnectedness of all things.

However, like many Indigenous languages, Tsėhesenėstsestotse faces the threat of extinction due to historical suppression and the dominance of English. In response, both the Northern Cheyenne Tribe in Montana and the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma have launched intensive language revitalization programs, including immersion schools and cultural camps, to ensure the language lives on and continues to carry the Cheyenne identity.

Resilience in the Face of Adversity: Adaptation and Modern Expressions

The Cheyenne people have endured immense hardship, including the devastating Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, forced relocation to reservations, and systematic attempts to eradicate their culture. Despite these traumas, their spirit of resistance and adaptation has been remarkable.

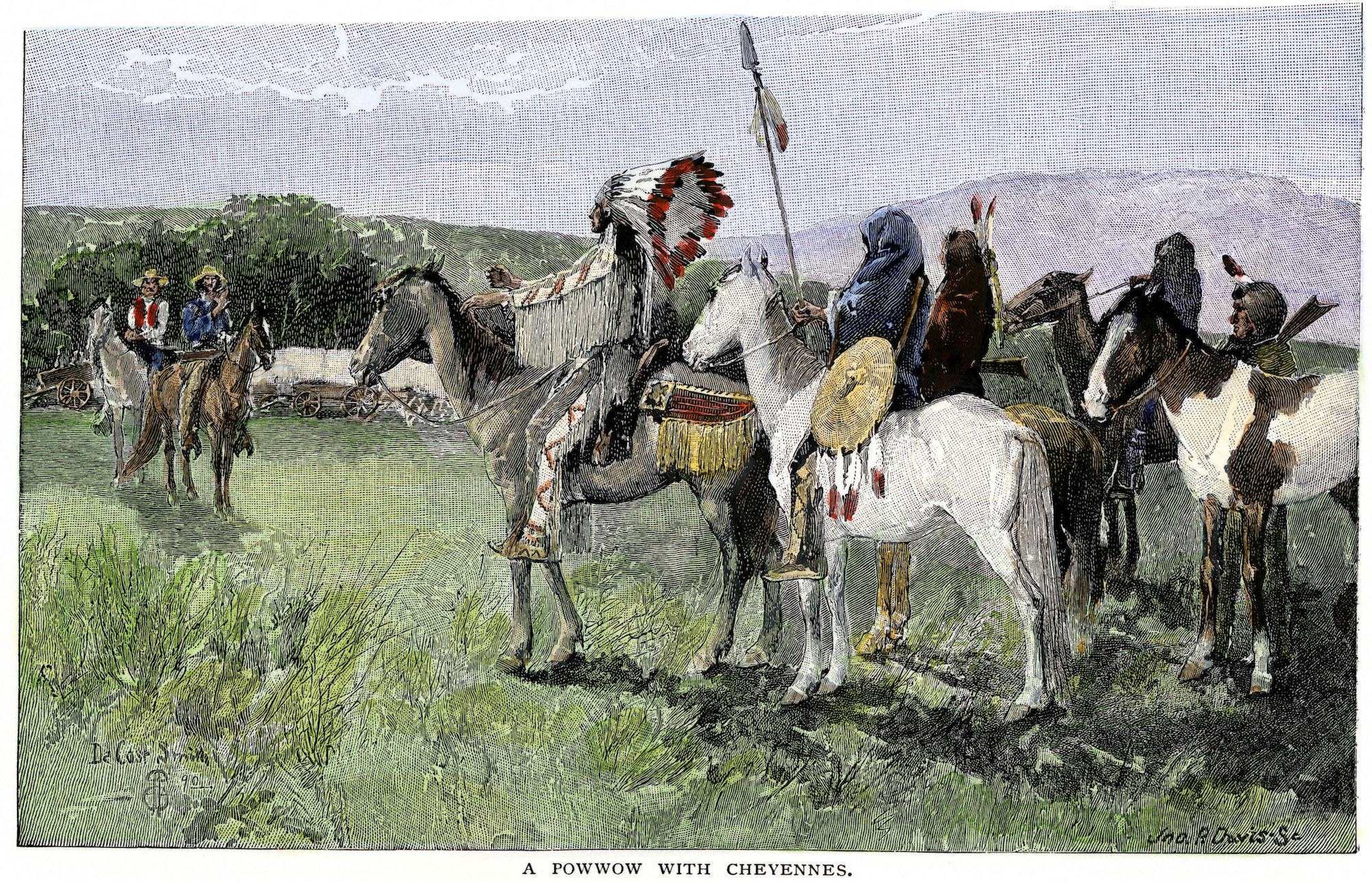

Today, Cheyenne cultural practices continue to evolve and find new expressions. Powwows, while not historically traditional Cheyenne ceremonies, have become vital intertribal gatherings that serve as powerful platforms for cultural celebration, sharing, and community building. Dancers in vibrant regalia, drummers, and singers share traditional songs and dances, allowing both tribal members and outsiders to witness the beauty and vitality of Indigenous cultures. For the Cheyenne, powwows are a way to honor their ancestors, teach their children, and proudly display their identity.

Contemporary Cheyenne artists, writers, and musicians also draw inspiration from traditional practices, translating ancient stories and symbols into modern forms. This creative expression ensures that Cheyenne culture remains dynamic and relevant in the 21st century, reaching new audiences and affirming Indigenous identity.

Education, both within tribal schools and through higher institutions, is increasingly focused on integrating traditional knowledge with Western curricula. Young Cheyenne people are encouraged to learn their language, participate in ceremonies, and understand their history, fostering a strong sense of pride and responsibility to carry on their heritage. Cultural camps, storytelling circles, and mentorship programs connect elders with youth, ensuring that the wisdom accumulated over centuries is not lost.

Looking Forward: A Living Legacy

The Cheyenne people, divided into two federally recognized tribes – the Northern Cheyenne Tribe of Montana and the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma – continue to assert their sovereignty and cultural distinctiveness. Their journey is a testament to the enduring power of culture as a source of strength, identity, and healing.

From the solemn beauty of the Sun Dance to the vibrant energy of a powwow, from the quiet wisdom of an elder’s story to the determined efforts of language revitalizers, Cheyenne cultural practices are not relics of the past. They are a living, breathing testament to a people who have faced profound challenges and emerged with their spirit intact. The echoes of the plains resonate strongly today, carrying the heartbeat of the Tsistsistas – a people deeply rooted in their traditions, resilient in their spirit, and determined to ensure their cultural legacy thrives for generations to come. Their story is a powerful reminder that true strength lies in knowing who you are, where you come from, and carrying that identity forward with courage and conviction.