Whispers of War: The Unbreakable Language of the Choctaw Code Talkers in WWI

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

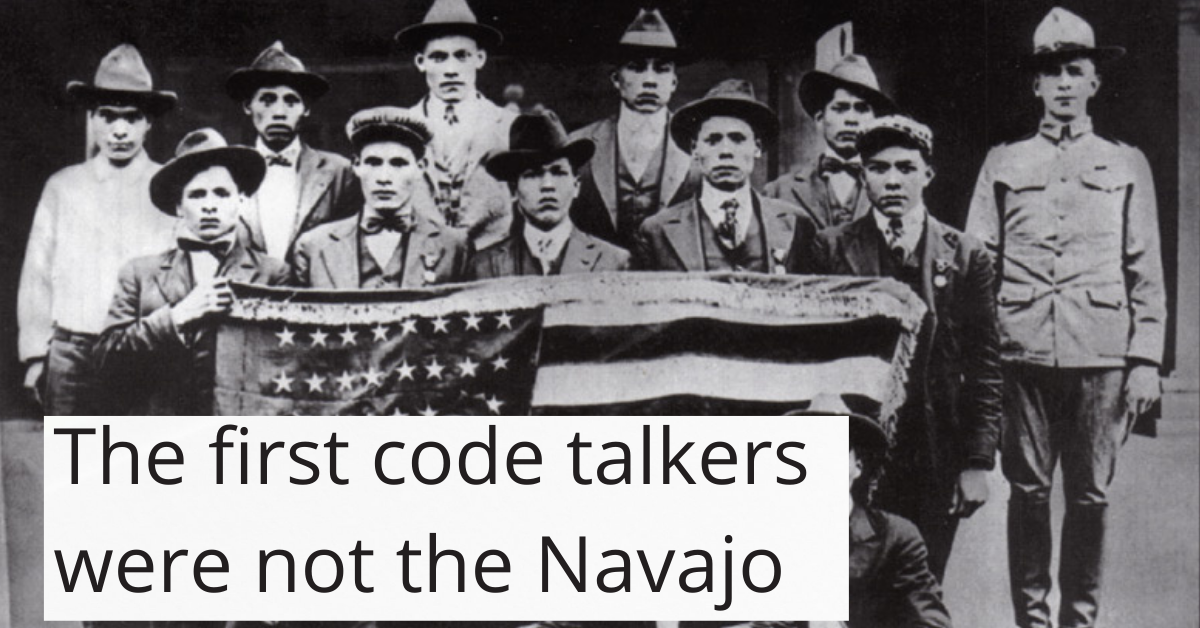

PARIS, FRANCE – Amidst the mud-soaked trenches and thunderous artillery of the First World War’s Western Front, a secret weapon emerged from an unlikely source, one that confounded the most sophisticated German intelligence and helped turn the tide of battle. It wasn’t a new weapon, nor a revolutionary tactic, but rather an ancient language, spoken by a small group of Native American soldiers from Oklahoma: the Choctaw Code Talkers. Their story, long shrouded in secrecy and only recently fully recognized, is a testament to ingenuity, patriotism, and the potent power of language in the crucible of war.

The year is 1918. The Great War has devolved into a brutal stalemate, characterized by trench warfare, devastating offensives, and a desperate struggle for tactical advantage. Communication on the battlefield was a nightmare. Telephone lines were easily tapped by German eavesdroppers, and couriers faced perilous journeys across no-man’s land. Every message, every order, every troop movement was vulnerable to interception. German intelligence was notoriously efficient, possessing linguists capable of deciphering nearly every code the Allies devised. The static crackle of telegraph wires often carried not just Allied messages, but also the chilling certainty that the enemy was listening.

This dire situation set the stage for a stroke of genius, or perhaps, serendipity. Colonel Alfred Bloor of the 142nd Infantry Regiment, part of the 36th "Arrowhead" Division, composed primarily of soldiers from Texas and Oklahoma, found himself in a particularly precarious position. His regiment was advancing, but his communications were compromised. It was then, in a moment of frustration, that he overheard two of his Choctaw soldiers conversing in their native tongue. An idea, seemingly outlandish, sparked in his mind. Could this obscure language, with no written form or dictionary accessible to the Germans, be the answer to their communication woes?

Bloor quickly consulted with Captain Andrew W. Robb, the regimental adjutant. Robb, who had lived in Oklahoma and was familiar with the Choctaw Nation, understood the potential. The Choctaw language was complex, tonal, and virtually unknown outside its community. It was the perfect cipher. Within hours, a daring experiment was proposed: use Choctaw soldiers to transmit vital messages over the open telephone lines.

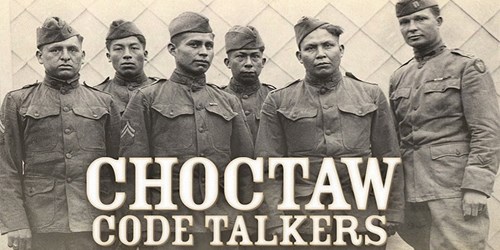

The initial group of Choctaw soldiers selected for this unprecedented task numbered just eight: Solomon Lewis, Tobias W. Frazier, Ben Carterby, Robert Taylor, Jeff Nelson, Pete Maytubby, George E. Lewis, and James Edwards. These men, like many Native Americans, had enlisted despite facing systemic discrimination and often being denied full citizenship rights in their own country. Yet, their patriotism was unwavering. They answered the call to arms, ready to fight for a nation that had, in many ways, wronged their ancestors.

The first test came on October 26, 1918, during the critical Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The 142nd Infantry was preparing to launch an attack on German positions in the Bois de Romagne sector. Orders needed to be transmitted quickly and securely. The Choctaw soldiers were given a message to translate and relay. According to military records, one message transmitted was: "Troops moving from east to west in Romagne. Artillery barrage to follow." This, and similar messages, were delivered in Choctaw, then re-translated by another Choctaw speaker at the receiving end.

The effect was immediate and profound. German listening posts, accustomed to deciphering English and French codes, were utterly bewildered. They intercepted the messages, but the strange, guttural sounds meant nothing to them. "The enemy’s telephone wire was tapped by the Germans, of course," recalled Private First Class Joseph Oklahombi, a Choctaw soldier renowned for his valor in combat, though not directly a Code Talker. "But they couldn’t understand our language, and we got our messages through."

The success of this initial trial led to the rapid expansion of the program. Over the next few days, eleven more Choctaw soldiers were identified and pressed into service as code talkers, bringing the total to 19. They were: Albert Billy, Mitchell Bobb, Fred Hoffman, Forest K. Brewer, Custer Nadley, Noel Johnson, Calvin Wilson, Victor Brown, Walter Veach, and the two initial speakers, Joseph Davenport and Joseph Jacob. These men became the living, breathing, unbreakable code.

The brilliance of their method lay in its simplicity and adaptability. There was no pre-set codebook. Instead, the Choctaw soldiers used their everyday language, often employing circumlocution for military terms that didn’t exist in Choctaw. For instance, "machine gun" might be translated as "little gun shoot fast," "artillery" as "big gun," and "hand grenade" as "little round iron." They even used the word "Choctaw" to refer to Americans, "German" to their enemy, and "ration" for a supply dump. This organic, evolving nature of their "code" made it impossible to crack, as there was no static dictionary for the Germans to obtain or analyze.

Their service was critical in several key engagements during the final weeks of the war. After the success at Bois de Romagne, the Choctaw Code Talkers were instrumental in the capture of Forest Farm and the vital town of St. Etienne. Their secure communication allowed for precise coordination of artillery bombardments, troop movements, and supply lines, saving countless Allied lives and significantly accelerating the American advance.

The German high command, baffled and frustrated, reportedly intercepted messages and concluded that the Americans must be using an "unknown Indian language" – a realization that offered no practical solution. The Choctaw language, a relic of ancient North America, proved more effective than any modern encryption technology of the era.

When the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, the Choctaw Code Talkers returned home, their extraordinary contribution largely unheralded. Their service, like that of many Native American soldiers, was often overlooked in the broader narrative of the war. Furthermore, the very secrecy that made them so effective also contributed to their obscurity. The U.S. military, recognizing the potential for future conflicts, classified their work, instructing the soldiers not to speak of it. This secrecy extended for decades, even after the Choctaw Code Talkers were long gone, with their story only slowly emerging into public consciousness.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that their story began to gain wider recognition, spurred by the efforts of historians and advocates. The Choctaw Nation, proud of their heroes, worked tirelessly to ensure their legacy was honored. In 1989, the French government, acknowledging their pivotal role, awarded the Chevalier de l’Ordre National du Mérite (Knight of the National Order of Merit) to the Choctaw Code Talkers, a posthumous honor for most.

Finally, in 2008, nearly 90 years after the war, the U.S. Congress passed the Code Talkers Recognition Act, awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to all Native American Code Talkers, including the Choctaw, who served in both World Wars. For the Choctaw Code Talkers of WWI, their families accepted the medals on their behalf, a long-overdue tribute to their immense sacrifice and ingenuity.

The Choctaw Code Talkers of WWI were more than just soldiers; they were linguistic warriors who leveraged their cultural heritage to achieve a strategic advantage that few could have foreseen. Their story stands as a powerful reminder of the hidden strengths within diverse populations, and the profound impact that unique cultural assets can have in times of crisis. From the battlefields of France to the halls of Congress, their whispers of war have finally roared into the annals of history, ensuring that the unbreakable language of the Choctaw will forever be remembered as a key to Allied victory in the Great War. Their legacy is not just one of military achievement, but also of cultural resilience, unwavering patriotism, and the enduring power of a language that helped save the world.