The Horse Whisperers of the Plains: The Enduring Legacy of Comanche Horsemanship

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

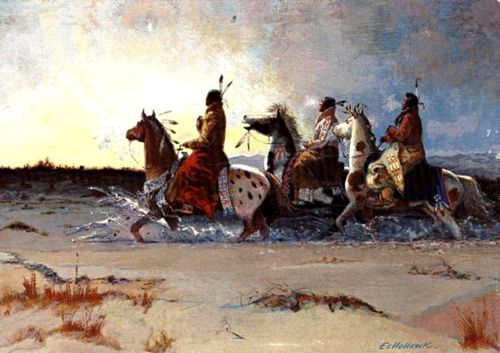

Imagine a vast, windswept plain, stretching to the horizon under an immense sky. Now, imagine a rider, not merely astride a horse, but seemingly fused with it—a living, breathing centaur. With the sun glinting off their braided hair and the wind whipping their rawhide fringe, they move with an effortless grace, an arrow nocked, eyes fixed on a distant buffalo herd or an approaching adversary. This indelible image, etched into the American consciousness, is the Comanche warrior, and their story is inextricably linked to the animal that transformed their world: the horse.

For centuries, the Comanche Nation, known to themselves as the Nʉmʉnʉʉ (The People), dominated the Southern Plains of North America, carving out an empire of unparalleled power and reach. From the Arkansas River south to the Rio Grande, and from the Rocky Mountains east to the Cross Timbers, this vast domain, known as the Comanchería, was not merely conquered but ruled by a people whose very identity was forged in the thunder of hooves. Their rise to prominence was swift, meteoric, and entirely dependent on their unparalleled mastery of the horse.

The Arrival of a Revolution

Before the horse, the Comanche were a relatively obscure hunter-gatherer group, living a challenging, pedestrian existence in the northern reaches of the Great Basin. Their movements were slow, their hunting arduous, and their reach limited. But then came the horse, a creature introduced to the Americas by the Spanish conquistadors, and later disseminated through trade and, crucially, through the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. As the Pueblo Indians drove the Spanish out of New Mexico, thousands of horses were liberated, scattering across the Southwest.

The Comanche were among the first indigenous groups on the Southern Plains to fully grasp the profound potential of this new animal. Around the early 1700s, they began acquiring horses, initially through trade with Ute intermediaries, and later, more aggressively, through raids on Spanish settlements and other tribes. Their adoption of the horse was not merely incremental; it was a wholesale transformation.

"No Indian tribe has ever had so many horses," wrote historian Rupert N. Richardson in The Comanche Barrier to South Plains Settlement. This wasn’t hyperbole. The Comanche didn’t just ride horses; they lived and breathed horses. Their entire social, economic, and military structure rapidly reoriented itself around this magnificent animal.

Masters of Horsemanship and Breeding

What set the Comanche apart was not just their acquisition of horses, but their unparalleled skill in horsemanship and their sophisticated understanding of selective breeding. From the youngest age, Comanche children were taught to ride, often bareback, their small hands gripping the horse’s mane. They learned to communicate with their mounts through subtle shifts in weight, knee pressure, and whispered commands, creating a bond that bordered on telepathic.

Comanche riders were renowned for their agility, speed, and endurance. They could cover vast distances, often riding 100 miles in a single day, their horses carrying them effortlessly across the plains. Their riding style was a marvel to behold: they could hang off the side of their horses at a full gallop, using the animal’s body as a shield while firing arrows or spears, a maneuver that baffled and terrified their enemies, including seasoned U.S. cavalrymen. They could shoot 20 arrows per minute from horseback, each one lethal.

This mastery wasn’t accidental. The Comanche actively bred their horses, selecting for specific traits like speed, stamina, intelligence, and a calm temperament under duress. They developed what became known as the "Comanche pony"—a hardy, agile, and remarkably intelligent horse, perfectly suited for the rigors of Plains life. These were not just animals; they were partners in every sense, revered and cared for with deep respect.

The Horse as an Economic and Social Engine

The horse revolutionized every aspect of Comanche life. Economically, it transformed them from subsistence foragers into formidable buffalo hunters and powerful traders. The buffalo, once a difficult prey, became a readily accessible resource. With horses, a single hunter could bring down multiple animals in a day, providing an abundance of meat, hides for lodges and clothing, and bones for tools. The communal buffalo hunt, a thunderous ballet of man, horse, and beast, became the cornerstone of their prosperity.

But the horse’s economic impact didn’t stop at hunting. It became the ultimate form of currency. The Comanche established vast trade networks, exchanging horses—often thousands at a time—for guns, ammunition, metal tools, blankets, and other goods with Spanish, Mexican, American, and other Native American groups. Their strategic location and their control over the horse supply made them indispensable trading partners, even to their adversaries. Taos and Santa Fe in New Mexico became vital hubs in this horse-driven economy.

Socially, horse ownership became the primary measure of wealth and status. A man’s prestige was often directly tied to the size of his horse herd. Raiding for horses became a major activity, a dangerous but rewarding endeavor that showcased bravery and skill. Young men honed their equestrian abilities in these raids, proving their worth to the community. Large herds also meant more mobility, more hunting capacity, and more power.

The "Lords of the Plains": Warfare and Dominion

Nowhere was the horse’s impact more profoundly felt than in warfare. The Comanche’s equestrian prowess made them the most feared warriors on the Plains, earning them the moniker "Lords of the Plains." Their military tactics were revolutionary. They could strike with lightning speed, vanish into the vast landscape, and reappear seemingly out of nowhere.

Their feigned retreats, designed to draw enemies into ambushes, were legendary. Their ability to maneuver rapidly, flank opponents, and engage in close-quarters combat while mounted gave them a decisive advantage. The U.S. Army, accustomed to conventional European warfare, found itself utterly outmatched and frustrated by the elusive, mobile Comanche forces. "They could not be caught and could not be stopped," lamented one exasperated officer.

The Comanchería was not just a homeland; it was an empire, protected by a formidable "Comanche Barrier" that halted Spanish, Mexican, and early American expansion for generations. During the "Comanche Moon"—the raiding season when the full moon provided ample light for nocturnal movements—Comanche war parties ranged far and wide, asserting their dominance and securing their resources.

Decline and the Enduring Spirit

The golden age of the Comanche, though spectacular, was ultimately unsustainable in the face of relentless external pressures. The late 19th century brought a devastating confluence of factors that led to their decline. The systematic extermination of the buffalo by white hunters, driven by both market demand and government policy aimed at subduing Native populations, starved the Comanche of their primary food source and economic backbone. Diseases like cholera and smallpox, to which they had no immunity, decimated their numbers.

Finally, the relentless campaigns of the U.S. Army, led by generals like William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Sheridan, adopted a scorched-earth policy, destroying villages and, critically, capturing or killing thousands of Comanche horses. Without their horses and the buffalo, the Comanche’s way of life, their power, and their freedom crumbled. By the mid-1870s, many bands, including that of the legendary Quanah Parker (son of a Comanche chief and a white captive, Cynthia Ann Parker), were forced onto reservations, marking the end of their nomadic existence and their dominion over the Plains.

The transition to reservation life was brutal, stripping away the very essence of Comanche identity. The open plains were replaced by confined plots, the thunder of hooves by the silence of forced settlement. Yet, even in this profound loss, the spirit of the horse endured.

A Legacy of Resilience and Pride

Today, the Comanche Nation continues to thrive, a testament to their resilience and adaptability. While the vast buffalo herds and the open range are gone, the horse remains a powerful symbol of their heritage, pride, and enduring connection to the land.

In modern Comanche culture, the horse is still central to many traditions. Comanche people actively participate in rodeos, showcasing their inherited equestrian skills. At powwows and cultural gatherings, the sight of Comanche riders, sometimes in traditional regalia, evokes the powerful images of their ancestors. Ceremonial rides and horse-related programs help to keep the knowledge and reverence for these animals alive, passing it down to new generations.

The Comanche Nation’s history with the horse is more than just a chapter in American history; it is a profound narrative of adaptation, power, and the unbreakable bond between a people and an animal. The horse transformed a small, pedestrian group into the undisputed "Lords of the Plains," enabling them to forge a vast empire and resist external forces for generations. Even after the tragic loss of their traditional way of life, the spirit of the horse continues to gallop through the heart of the Comanche people, a living reminder of their strength, their ingenuity, and their enduring legacy on the American frontier. The echoes of those thunderous hooves still resonate across the vast plains, a timeless testament to the horse whisperers of the Comanche Nation.