Echoes of Ink and Iron: The Enduring Legacy of Crow Historical Treaties

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Pen Name]

The vast plains of what is now Montana and Wyoming hold stories etched not just in the wind-swept landscapes but in the faded ink of treaties signed long ago. These documents, often misunderstood and frequently violated, form the bedrock of the modern Crow Nation (Apsáalooke). Far from mere historical relics, the Crow’s treaties with the United States government are living documents, foundational to their sovereignty, land rights, and cultural identity. They are a testament to a people’s resilience, strategic foresight, and the enduring struggle to protect their ancestral way of life against the relentless tide of westward expansion.

To understand the profound impact of these treaties, one must first appreciate the Crow people before contact. The Apsáalooke, or "children of the large-beaked bird," were a powerful, nomadic plains tribe, renowned for their horsemanship, distinctive pompadour hairstyles, and fierce independence. Their traditional territory was immense, stretching across millions of acres encompassing the Yellowstone River valley, the Bighorn Mountains, and vast stretches of land rich in buffalo, timber, and mineral resources. They were often in conflict with neighboring tribes, particularly the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who were also expanding their territories. This intricate web of inter-tribal relations would, ironically, play a significant role in their diplomatic dealings with the encroaching American government.

The First Defining Lines: The 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty

The mid-19th century brought an unstoppable wave of American settlers, prospectors, and entrepreneurs pushing westward. The Oregon Trail, the California Gold Rush, and the burgeoning desire for transcontinental railroads necessitated "peace" and defined boundaries. This set the stage for the first monumental treaty: the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851.

Gathered near present-day Torrington, Wyoming, representatives from the United States government met with delegates from various Plains tribes, including the Crow. The primary goal for the U.S. was to secure safe passage for emigrants and to minimize conflicts by clearly delineating tribal territories. For the Crow, it was an opportunity to formalize their claims to their ancestral lands, particularly against the incursions of their traditional enemies.

The 1851 treaty recognized an enormous Crow territory, estimated at nearly 38 million acres. This vast expanse included much of what is now southern Montana and northern Wyoming. In exchange for acknowledging these boundaries and allowing the construction of roads and military posts, the Crow were promised annuities – goods, provisions, and services – for fifty years.

While seemingly beneficial on paper, the 1851 treaty was fraught with immediate and long-term problems. Many tribes did not fully understand or agree to the concept of fixed, surveyed boundaries. Furthermore, the U.S. government often failed to deliver the promised annuities or protect tribal lands from settler encroachment. For the Crow, the treaty’s definition of their territory, while vast, became a magnet for their enemies, who viewed the U.S.-drawn lines as an invitation to contest land claims. As historian Frederick E. Hoxie notes in "Parading Through History: The Crow Indians in the Twentieth Century," the treaty "set forth a tribal geography that the Crow believed would secure their future. They were sadly mistaken."

A Shrinking World: The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty

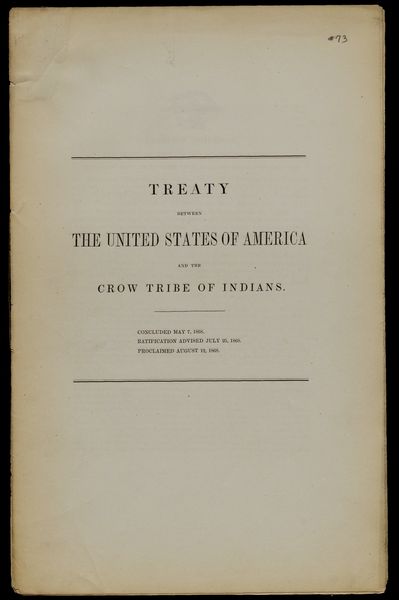

The years following 1851 saw escalating tensions. The discovery of gold in Montana in the early 1860s led to the creation of the Bozeman Trail, a shortcut from the Oregon Trail directly through prime hunting grounds and treaty lands, including those of the Crow. This influx of miners and settlers ignited fierce resistance from the Lakota and Cheyenne, leading to Red Cloud’s War (1866-1868), one of the few instances where a Native American coalition decisively defeated the U.S. Army.

The U.S. government, seeking to end the costly war, convened another Fort Laramie Treaty Council in 1868. This treaty is often remembered for its provisions with the Lakota, granting them the Great Sioux Reservation. However, it also significantly impacted the Crow. Unlike many other tribes, the Crow had largely maintained an alliance with the U.S. during Red Cloud’s War, viewing the Lakota and Cheyenne as their primary adversaries. This strategic decision was championed by influential leaders like Chief Plenty Coups, who understood the precarious position of his people.

The 1868 treaty drastically redefined Crow territory, reducing it from 38 million acres to approximately 8 million acres, centered around the Yellowstone and Bighorn River valleys. While still substantial, this was a massive cession of land. In exchange, the Crow were promised a permanent reservation, annuities, and support for their transition to an agricultural lifestyle, including schools and farming implements. The U.S. sought to "civilize" the tribes, believing that settled agricultural life was the only path to their survival.

Chief Plenty Coups, whose wisdom and foresight would guide his people through tumultuous times, understood the gravity of the moment. He famously recounted a dream where he saw a chickadee, a small bird, outsmarting larger, more powerful birds. He interpreted this to mean that the Crow, though smaller in number than the Americans, could survive by adapting and using their wits. He advised his people to cooperate with the U.S. in certain respects to preserve their core identity. As he later recounted, "I saw that the Iron Horse [railroad] was coming, and I knew that the buffalo were going." He recognized that the old way of life was ending and that survival lay in a painful adaptation.

The 1868 treaty, though a painful reduction of their ancestral lands, was a strategic move for the Crow. It secured a defined territory against their enemies and offered a degree of protection and resources from the U.S. government, however inconsistently delivered. This treaty, therefore, laid the foundation for the present-day Crow Indian Reservation.

The Era of Allotment and Further Cessions

Even after 1868, the Crow’s land base continued to erode. Subsequent agreements and legislative acts further diminished their territory. In 1873, a large portion of the western part of their reservation was ceded. In 1880, another cession occurred, and in 1891, the Act of March 3, 1891, drastically reduced the reservation to its current size of approximately 2.2 million acres. These cessions were often the result of immense pressure from settlers, railroads, and the government’s insatiable demand for land and resources.

Perhaps the most devastating policy was the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887. This act aimed to break up tribal communal land ownership by allotting individual parcels of land to Native Americans and selling off the "surplus" lands to non-Native settlers. While the Crow Reservation was initially protected from immediate allotment, it eventually faced similar pressures. The Dawes Act, ostensibly designed to integrate Native Americans into mainstream society, instead led to massive land loss, fragmentation of tribal communities, and profound economic hardship.

The Enduring Legacy: Sovereignty and Self-Determination

Despite the repeated land cessions, broken promises, and the profound cultural disruption caused by U.S. policies, the Crow people endured. The treaties, however flawed, remain central to their identity and legal standing. They are not merely historical documents but legal contracts between two sovereign nations.

Today, the Crow Nation, headquartered in Crow Agency, Montana, is a vibrant and self-governing entity. The treaties, particularly the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, are the basis for their inherent sovereignty and their rights to manage their land, water, and resources. They are actively engaged in defending these rights, from complex water rights litigation to managing mineral resources on their reservation. The Crow Nation operates its own government, courts, and essential services, embodying the spirit of self-determination.

The story of the Crow treaties is a microcosm of the broader history of U.S.-Native American relations: a complex tapestry of conflict, negotiation, betrayal, and resilience. It highlights the vast cultural chasm between Indigenous concepts of land stewardship and Western notions of private property. Yet, it also underscores the strategic acumen of leaders like Plenty Coups, who, in the face of overwhelming odds, navigated a path for their people’s survival.

The echoes of ink and iron from those 19th-century treaty councils still reverberate across the Crow Reservation. They serve as a powerful reminder of promises made and broken, but more importantly, of a people who, against all odds, continue to thrive, honoring their ancestors and safeguarding their sovereignty for future generations. The Crow Nation stands as a testament to the enduring power of a people who have never forgotten who they are, rooted in the very lands their ancestors fought so hard, and so strategically, to protect.