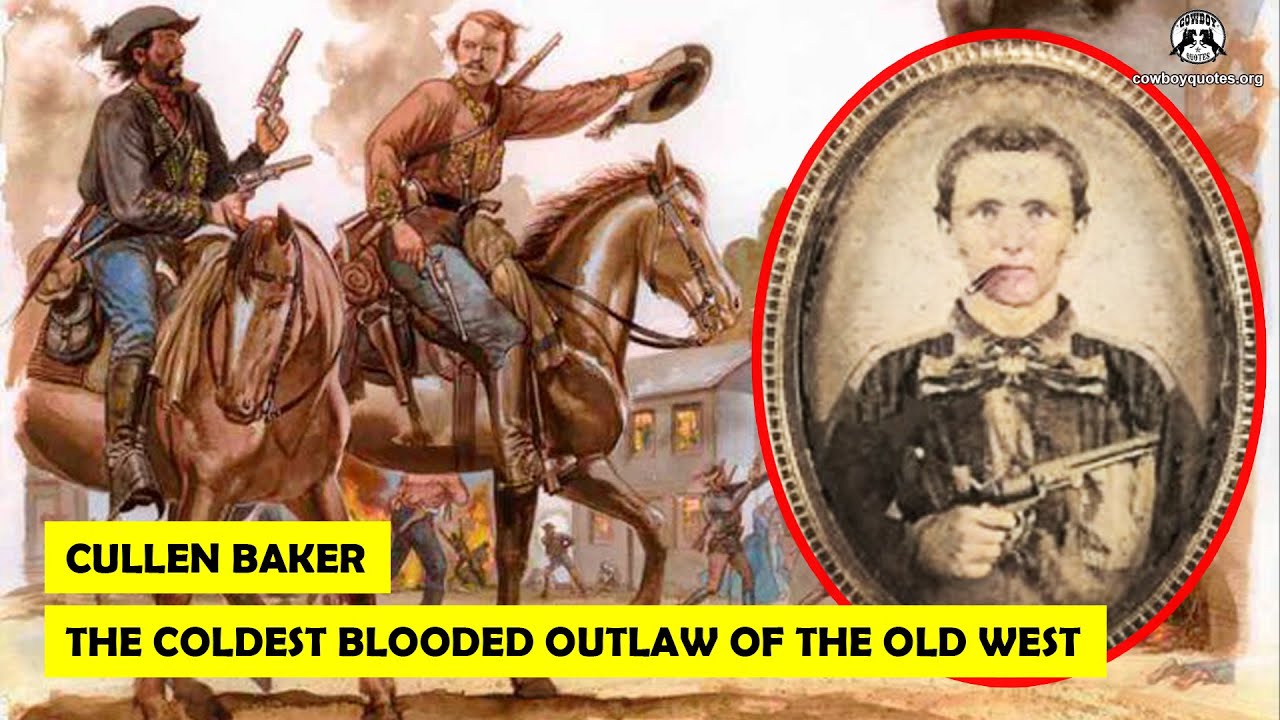

Cullen Montgomery Baker: The Unvanquished Ghost of Reconstruction Texas

In the rugged, unforgiving landscape of post-Civil War Texas, where the echoes of battle mingled with the harsh realities of Reconstruction, a figure emerged from the shadows, carving a legend born of blood, defiance, and an unyielding spirit. Cullen Montgomery Baker, a name that still resonates with both awe and dread, was not merely an outlaw; he was a living symbol of the deep-seated resentments and violent struggles that defined the South in the wake of its crushing defeat. To some, he was a folk hero, a latter-day Robin Hood fighting against perceived federal tyranny; to others, he was a ruthless killer, a cold-blooded terrorist who preyed on the vulnerable. His story, shrouded in the mist of legend and conflicting accounts, offers a stark window into the fractured soul of a nation grappling with its identity.

Born in 1835 in Cherokee County, Texas, Cullen Baker’s early life was typical of a frontier upbringing – marked by hard labor, self-reliance, and an ingrained sense of independence. He was a product of his environment, a place where disputes were often settled with a quick temper and a quicker draw. Even before the war, Baker had a reputation for violence, involving himself in feuds and altercations that hinted at the darker path he would eventually tread. However, it was the Civil War that truly forged the man who would become infamous.

Like many young Southern men, Baker answered the call to arms, enlisting in the Confederate Army. He served as a scout and a guerrilla fighter, honing his skills in marksmanship, horsemanship, and the brutal art of ambush. The war hardened Baker, instilling in him a deep-seated animosity towards Union authority and a profound sense of loyalty to the Southern cause. The defeat of the Confederacy, followed by the imposition of Reconstruction policies, was, for men like Baker, not merely a loss of a war but an existential assault on their way of life, their pride, and their very identity.

For many Southerners, the Reconstruction era (1865-1877) was not a period of healing but one of continued subjugation. Federal troops occupied the South, the Freedmen’s Bureau was established to aid newly emancipated slaves, and state governments were often run by "carpetbaggers" (Northerners who moved South) and "scalawags" (Southerners who cooperated with Reconstruction). This perceived Northern oppression, coupled with the profound social upheaval of emancipation, created a fertile ground for resentment, resistance, and outright violence. It was in this volatile atmosphere that Cullen Baker transformed from a hot-headed local into "The King of the Border," a notorious outlaw whose name struck fear into the hearts of federal agents and their sympathizers.

Baker’s reign of terror began in earnest around 1867. He quickly became the scourge of Northeast Texas and Southwest Arkansas, targeting Union soldiers, Freedmen’s Bureau agents, local officials, and anyone he perceived as an enemy of the "true" Southern way of life. His modus operandi was brutal and efficient: ambushes, assassinations, and cold-blooded killings. He was said to be unerring with his Colt revolvers, often carrying two and using them with deadly efficiency. Stories abound of his almost supernatural ability to evade capture, slipping through the dense piney woods and swamps that were his natural domain.

To his sympathizers, largely disaffected Confederates, poor whites, and those who resented federal occupation, Baker was a folk hero. They harbored him, fed him, and provided him with intelligence, seeing him as a lone wolf bravely striking back against an unjust system. His defiance resonated with their own sense of powerlessness and humiliation. They romanticized his actions, turning him into a symbol of Southern resistance – a wild, untamed spirit who refused to bow to the victors. This perception, however, stood in stark contrast to the reality of his victims.

To Unionists, freedmen, and federal authorities, Baker was nothing short of a cold-blooded terrorist. Accounts describe him as a man consumed by hatred, whose violence was indiscriminate and chilling. While the exact number of his victims remains a subject of historical debate – estimates vary wildly from a dozen to over fifty – there is no doubt that Baker was responsible for numerous killings, many of them brutal and premeditated. He was particularly known for his animosity towards black people, viewing their newfound freedom as an affront to the social order he believed in. This aspect of his character, often glossed over by those who romanticize him, firmly places him within the broader context of white supremacist violence that plagued the Reconstruction South.

One of the interesting facts about Baker is the sheer difficulty historians face in separating fact from the embellished legend. Contemporary newspapers, often biased, painted him either as a monster or a martyr, depending on their political leanings. Local lore, passed down through generations, further blurred the lines. What is clear, however, is that Baker commanded a small, loyal band of followers who shared his anti-Reconstruction sentiments and participated in his violent escapades. Together, they became a persistent thorn in the side of federal and state authorities, who were often ill-equipped or unwilling to pursue them effectively in the vast, untamed wilderness.

The authorities, both state and federal, mounted numerous attempts to capture Baker. Posses were formed, rewards were offered (reportedly as high as $1,000, a significant sum at the time), and the full force of the law was theoretically brought to bear. Yet, Baker remained elusive, his intimate knowledge of the terrain and the widespread local sympathy he enjoyed making him nearly untouchable. He became a ghost, fading into the swamps and forests whenever danger approached, only to reappear with deadly force elsewhere.

But even the most elusive specter can be brought to ground, and for Cullen Baker, the end came not from a pursuing posse, but from within his own bloodline. On January 6, 1869, while reportedly asleep or incapacitated due to illness or drink, Baker was shot and killed by his cousin, Thomas Baker. The motives behind Thomas Baker’s betrayal are complex: some accounts suggest he was acting out of fear, fearing Cullen’s increasingly erratic and violent behavior, while others claim he was motivated by the substantial reward money on Cullen’s head. The official story often leans towards the latter, highlighting the pervasive influence of greed even among kin.

After his death, Cullen Baker’s body was taken to Jefferson, Texas, where it was put on public display, a grim trophy meant to reassure a terrorized populace and demonstrate the end of his reign. His death was met with mixed reactions: relief for those who had suffered under his violence, and lament for those who saw him as their champion. The era of the notorious outlaw had seemingly come to an end, but his legend was far from over.

Cullen Montgomery Baker remains a complex and controversial figure, a stark embodiment of the deep divisions and raw violence that characterized post-Civil War Texas. He was a product of his time, a man whose personal propensity for violence found fertile ground in the political and social upheavals of Reconstruction. His story forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about heroism and villainy, justice and vengeance, and the ways in which historical narratives are shaped by perspective.

Historians grapple with the duality of Baker’s image. Was he a freedom fighter, resisting an oppressive federal government? Or was he a bloodthirsty murderer, exploiting the chaos of the era for his own violent ends? The truth, as is often the case, lies somewhere in the murky middle. He was, undoubtedly, a killer driven by deep-seated prejudice and a violent nature. Yet, his actions were also fueled by a profound sense of betrayal and resentment that was shared by many white Southerners. His defiance, however misguided and brutal, struck a chord with those who felt their world had been irrevocably shattered.

Today, Cullen Montgomery Baker is remembered as a significant figure in Texas outlaw lore, often mentioned alongside other notorious figures like John Wesley Hardin or Sam Bass. His legend, though often sanitized and romanticized, continues to fascinate, a testament to the enduring human interest in rebels and outcasts who defy authority, even when their methods are morally reprehensible. He stands as a powerful reminder of the bitter legacy of the Civil War and the painful, often violent, birth of a new America, where old loyalties clashed with new realities, and men like Cullen Baker became unvanquished ghosts of a time that refused to be forgotten.