Dust and Dynamite: The Fiery Fourth in America’s Mining Towns

The air in Granite Gulch usually hummed with the mournful grind of the stamp mill, the rhythmic clang of picks echoing from deep within the earth, and the low, guttural curses of men whose lives were measured in rock and dust. It was a world of perpetual twilight underground, and a harsh, sun-baked or snow-choked existence above. Danger was a constant companion, prosperity a fleeting dream, and the company store a ubiquitous reminder of an unyielding hierarchy.

But for one day, every year, a fragile alchemy transformed these desolate outposts of industry into vibrant, defiant spectacles of patriotism. On the Fourth of July, the mining towns of America – scattered like forgotten jewels across the rugged spines of the Appalachians, the Rockies, and the Sierra Nevada – paused their relentless toil. For 24 hours, the heavy mantle of hardship lifted, replaced by a fierce, almost desperate, celebration of independence, community, and the enduring, if often elusive, American dream.

These were not the genteel, flag-waving parades of New England villages, nor the grand civic displays of burgeoning cities. The Fourth in a mining town was a raw, visceral affair, born of necessity and tempered by the grim realities of life at the edge. It was a day when the very ground beneath their feet, usually a source of both sustenance and peril, became a stage for a collective outpouring of spirit.

The Weight of the World, Lifted for a Day

To understand the intensity of these celebrations, one must first grasp the daily grind that preceded them. A miner’s life was a testament to grit, endurance, and often, quiet despair. They were the engine of a rapidly industrializing nation, extracting the coal, copper, gold, and silver that fueled its progress. Yet, their own lives were often brutish and short. Black lung, silicosis, cave-ins, explosions – these were not abstract threats but ever-present specters. Wages were meager, hours long, and the company store often ensured that any earnings circled back to the mine owners, trapping families in a cycle of debt.

In this environment, the Fourth of July was more than just a holiday; it was a psychological release valve. It was a collective gasp of fresh air after weeks spent inhaling dust. "For a single day," Old Man Tiber, a grizzled Cornishman who had seen more dark than light in his sixty years in the Leadville mines, was known to declare, his voice raspy from years of coal dust, "we remember why we came here. Not for the gold, necessarily, but for the promise. And on the Fourth, the promise shines a little brighter."

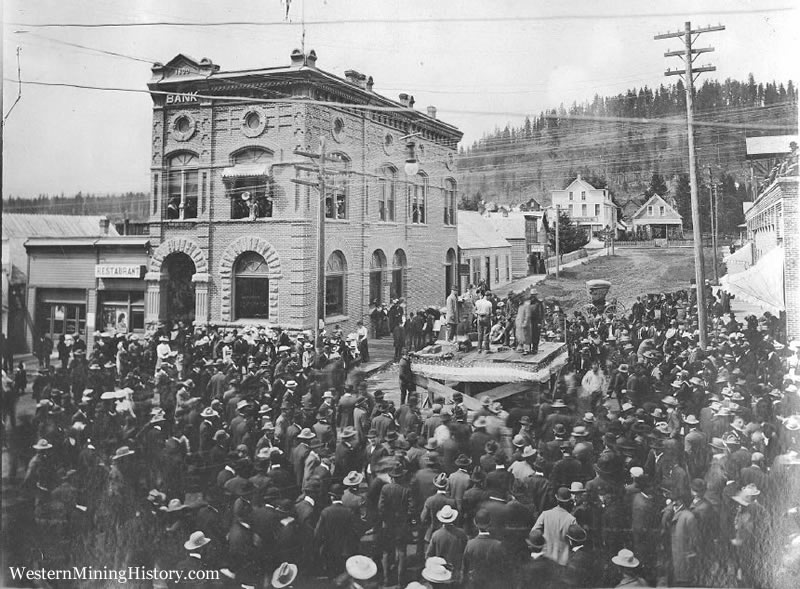

This promise was particularly resonant for the kaleidoscope of immigrants who formed the backbone of these mining communities. From the sun-baked hills of Italy to the green valleys of Ireland, from the Slavic heartlands to the rugged peaks of Scandinavia, men and their families poured into these isolated camps, seeking opportunity. They brought with them their languages, their foods, their faiths, and their traditions. The Fourth became a crucible where these diverse cultures, often clashing in daily life, found common ground in a shared, albeit newly adopted, national identity. It was a day to assert, loudly and proudly, their claim to being American.

A Symphony of Scraps and Spirit

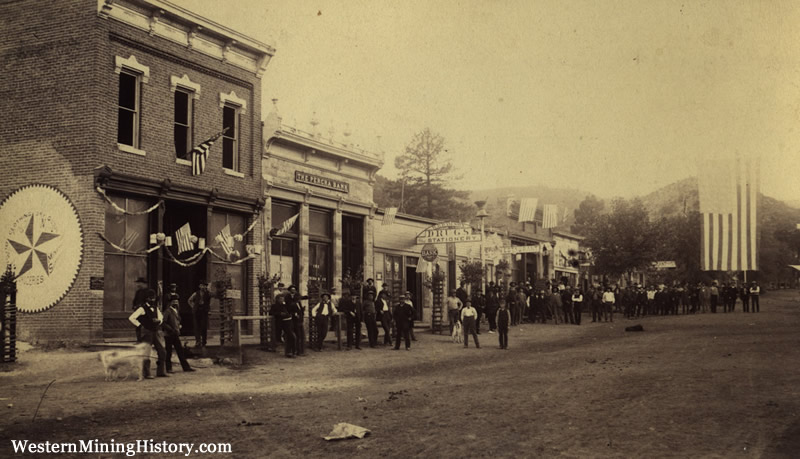

The preparations for the Fourth would begin weeks in advance, a testament to the community’s yearning for respite. Committees, often comprising representatives from various ethnic groups, would form. Women would sew flags from scraps of fabric, children would collect discarded cans for rudimentary firecrackers, and the men, after their shifts, would work on constructing makeshift bandstands or cleaning the dusty town square.

On the morning of July 4th, the transformation was astonishing. The ubiquitous dust, at least for a few hours, seemed to settle. The air, usually heavy with the metallic tang of iron or the acrid smell of coal smoke, was now filled with the scent of pine boughs, gunpowder, and the tantalizing aroma of roasting meat.

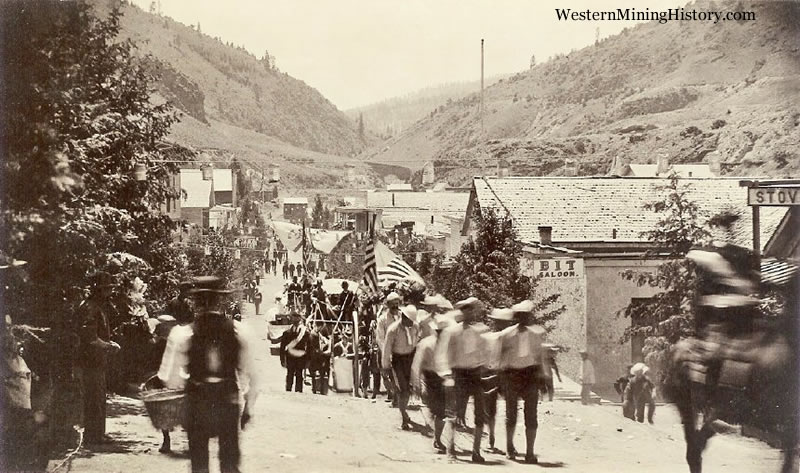

The day would typically kick off with a parade, humble yet heartfelt. It wasn’t the spectacle of Fifth Avenue, but it possessed a profound sincerity. Miners, their faces scrubbed clean and their work clothes replaced by their Sunday best, would march, often led by a local brass band whose instruments might be dented but whose tunes were played with gusto. The volunteer fire brigade, their engine polished to a gleam, would follow, a symbol of communal protection. Children, their faces smeared with berry juice or dust, would wave small, hand-made flags, their cheers echoing off the canyon walls.

Following the parade, the town would gather for speeches. Often delivered by a local schoolteacher, a preacher, or even a mine foreman (sometimes with thinly veiled company propaganda), these orations were nevertheless imbued with potent symbolism. They spoke of liberty, sacrifice, and the enduring spirit of America. They invoked Washington, Lincoln, and the ideals of freedom that, however distant they might seem in the daily grind, were deeply cherished. "We may dig in the dark," one such orator in Cripple Creek was recorded to have said in 1905, "but our hearts beat for the light of freedom!"

Feasting, Frolic, and Fiery Displays

The afternoon was given over to communal feasting and frolic. Tables would groan under the weight of potluck dishes – Italian pastas next to Irish stews, Slavic pierogi beside American apple pies. Barbecues, often involving an entire hog roasted over an open pit, would be the centerpiece, a rare indulgence for communities where meat was often a luxury. Foot races, sack races, pie-eating contests, and tug-of-war battles would pit the mine’s various ethnic groups against each other in friendly, boisterous competition, momentarily dissolving the tensions that often simmered beneath the surface.

Music was omnipresent. The local band would play patriotic tunes, but these would quickly give way to the more familiar sounds of home: Irish jigs, Italian folk songs played on accordions and mandolins, Slavic polkas, and robust German drinking songs. Dancing would erupt spontaneously, a joyous, uninhibited release of pent-up energy, as men and women spun and twirled, their laughter mingling with the music.

As dusk settled, the air would thicken with anticipation. The mining towns, often nestled in deep valleys or perched precariously on mountainsides, offered a unique backdrop for the grand finale: the fireworks. These displays, while perhaps not as professionally orchestrated as today’s spectacles, were often more dangerous and thrilling. Miners, accustomed to handling dynamite and black powder, would fashion their own pyrotechnics. Bonfires would be lit on surrounding hillsides, casting an orange glow across the landscape. Then, with a series of bangs and whistles, homemade rockets would shoot skyward, exploding in brilliant, if often erratic, bursts of color against the vast, star-dusted canvas of the mountain night. The smell of gunpowder, usually associated with the grim business of blasting rock, now became the scent of celebration, of fleeting beauty.

The danger was real. Accounts from the era speak of minor burns, singed eyebrows, and even occasional larger mishaps, yet these only added to the legend of the mining town Fourth. It was a day to live fully, to embrace the thrill, to stare down the darkness with a defiant blaze of light.

The Lingering Embers

Even in company towns, where the mine owner’s influence permeated every aspect of life, and the company store dictated life’s every turn, the Fourth offered a brief, sanctioned respite. The companies, recognizing the need to maintain morale and prevent outright rebellion, often tolerated, and sometimes even facilitated, these celebrations. A happy, or at least momentarily content, workforce was a productive one. Yet, there was always an underlying tension, a subtle reminder that this freedom was, in many ways, conditional.

The next morning, the dust would settle, quite literally. The festive bunting would droop, the echoes of laughter would fade, and the smell of gunpowder would be replaced by the familiar tang of industry. Miners would once again descend into the earth, their faces grim, their bodies aching, but perhaps with a faint, lingering echo of the previous day’s joy.

The Fourth of July in America’s mining towns was more than just a holiday. It was a testament to the human spirit’s unyielding desire for freedom, community, and joy, even in the most arduous of circumstances. It was a day when the stark realities of labor were momentarily overshadowed by the ideals of liberty, when diverse peoples forged a shared identity in the crucible of celebration. These were the moments that illuminated the profound darkness of their daily lives, reminding them, however briefly, that beyond the dust and the danger, there was still a flickering flame of hope, a memory of light in the profound darkness. The echoes of those fireworks, those songs, and those defiant cheers, still resonate in the canyons and hollows, a powerful reminder of how hard-won and deeply cherished freedom truly was for those who built America from the ground up.