Dust, Dreams, and Destiny: The Enduring Legend of America’s Great Western Cattle Trail

The American West, a vast expanse of untamed wilderness and boundless opportunity, has always been fertile ground for legends. From the gold rushes to the gunfighters, the story of its expansion is woven into the very fabric of the nation’s identity. Yet, among the most enduring and romanticized sagas is that of the American cowboy and the epic cattle drives that carved an indelible mark across the landscape. While the Chisholm Trail often hogs the spotlight, it is the Great Western Cattle Trail – longer, wilder, and more enduring – that truly embodies the grit, grandeur, and sometimes grim reality of this iconic era. It is a tale of dust, dreams, and the relentless pursuit of destiny, a journalistic journey into the heart of a legend that continues to captivate the American imagination.

Post-Civil War America presented a stark economic paradox. In Texas, millions of Longhorn cattle, lean and hardy, roamed wild and free, valued at little more than $3 to $5 a head. Yet, in the burgeoning cities of the North and East, a rapidly growing population yearned for beef, willing to pay upwards of $30 to $50 per head. The challenge was immense: how to transport these vast herds across a thousand miles of untamed frontier, through hostile territories, unforgiving weather, and the sheer logistical nightmare of a cattle drive. The answer lay in the ingenuity, endurance, and sheer audacity of the American cowboy.

The first major trails, like the Sedalia (or Shawnee) Trail, emerged shortly after the war, but disease and conflicts with farmers led to their decline. The Chisholm Trail, blazing a path to Abilene, Kansas, quickly became dominant, but as settlement pushed westward and railroads extended their reach, a new, more westerly route was needed – one that skirted the burgeoning farmlands and pushed deeper into the frontier. This was the genesis of the Great Western Cattle Trail.

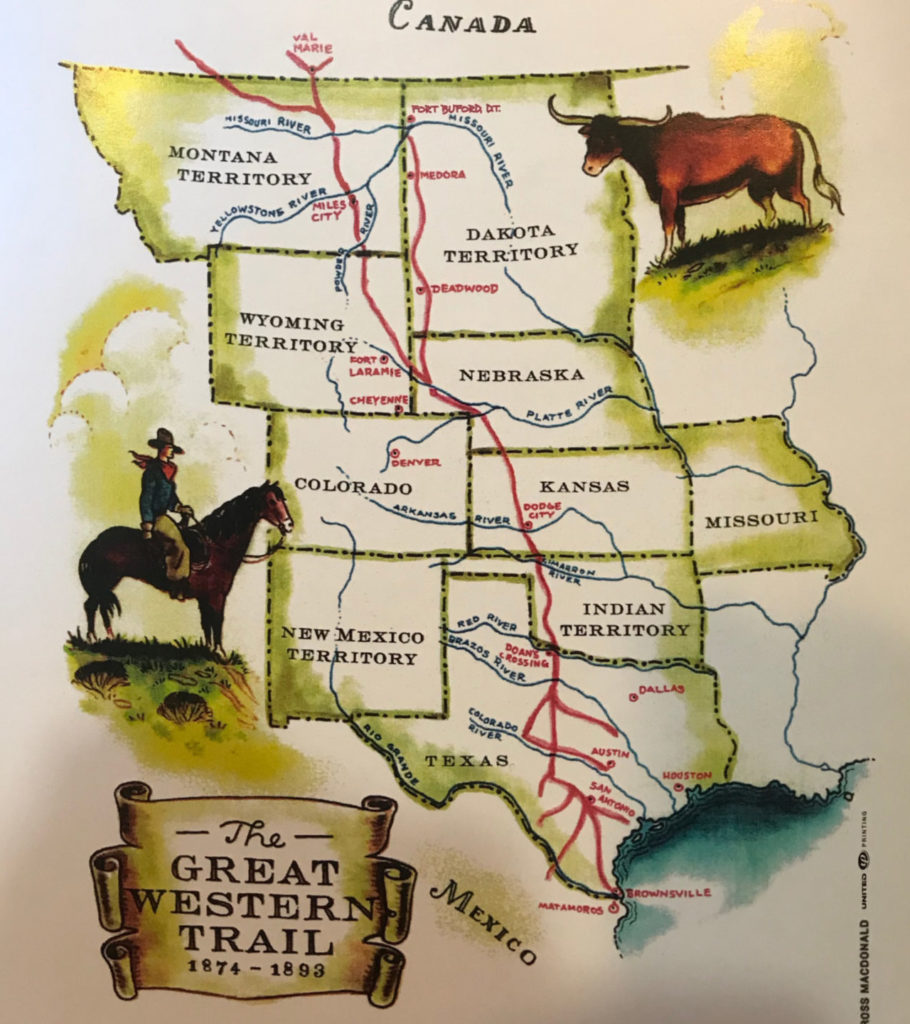

Born around 1874, the Great Western Cattle Trail stretched an astonishing 1,500 miles, making it one of the longest and most significant of the post-Civil War cattle trails. Originating in Bandera, Texas, and other points near San Antonio, it snaked its way northward, crossing the Red River into Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), traversing vast swathes of what would become Kansas, Nebraska, and even reaching as far north as Ogallala, Nebraska, and Miles City, Montana. Unlike its eastern counterparts, the Great Western remained a vital artery for cattle for a longer period, primarily because it ventured further west, staying ahead of the advancing tide of homesteaders and barbed wire fences that would eventually spell the end of the open range.

The cattle drive itself was a monumental undertaking, a carefully choreographed dance of man, horse, and beast against the elements. A typical drive might involve 2,500 to 3,000 head of cattle, guided by a crew of ten to fifteen cowboys, a trail boss, a cook, and his chuck wagon. The day began before dawn, with the cook’s call shattering the silence, followed by strong coffee and a hearty, if simple, breakfast. As the sun rose, the herd was "drifted" onto the trail, slowly moving northward at a pace of ten to fifteen miles a day.

The cowboys, the true heroes of this saga, were a diverse lot, often romanticized into a singular image of the white, Anglo-Saxon gunslinger. In reality, a significant portion were Mexican vaqueros, whose skills and knowledge of herding were foundational to American cowboy culture, and African Americans, many of whom were freed slaves seeking opportunity and independence in the West. Native Americans also worked as cowboys, bringing invaluable knowledge of the land. They were young, often in their late teens or early twenties, earning a meager $25 to $40 a month for back-breaking work. As historian L.F. Sheffy noted in "The Cattlemen’s Frontier," "The cowboy’s life was not one of leisure and adventure, but of long hours, hard work, and constant danger."

The dangers were manifold. Stampedes, often triggered by a sudden noise, a lightning strike, or even a nervous steer, were the most terrifying. A thundering mass of thousands of panicked cattle could crush a man and horse in an instant. River crossings were equally perilous, with swollen waters threatening to sweep away cattle and cowboys alike. The Red River, a formidable barrier, claimed many lives and herds. "The Red River was always a gamble," one old-timer reportedly recounted, "you either made it across, or you didn’t. There wasn’t much in between."

Beyond natural perils, there were human threats. Rustlers, ever on the prowl, attempted to cut off strays or even entire sections of the herd. Conflicts with Native American tribes, whose lands were being encroached upon, were also a reality, though often exaggerated in popular lore. Most tribes preferred payment of tolls for passage rather than direct confrontation, but skirmishes did occur. Later, as the trail pushed through more settled areas, "nesters" – homesteaders and farmers – began to fence their lands, leading to "fence cutting wars" and further narrowing the open range.

At the end of the trail lay the fabled cowtowns: Dodge City, Kansas, and later Ogallala, Nebraska. Dodge City, immortalized as "Queen of the Cowtowns," was a raw, raucous destination where months of pent-up energy, danger, and loneliness exploded into a frenzied mix of gambling, saloons, and brothels. Here, cowboys received their pay, blew off steam, and prepared for the long journey back to Texas. The cattle, meanwhile, were loaded onto newly built railroad cars, bound for the slaughterhouses of Chicago and other meatpacking centers. Ogallala, often called the "Cowboy Capital of Nebraska," served a similar function further north, a vital hub for cattle heading to northern markets and even the vast ranchlands of Wyoming and Montana. These towns were boiling cauldrons of ambition and excess, often needing famous lawmen like Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson to impose a semblance of order.

The economic engine driving these trails was immense. Millions of cattle traversed the Great Western, feeding a hungry nation and fueling a nascent industry. It wasn’t just beef that moved north; ideas, cultures, and people traveled both ways, shaping the social landscape of the West. The trail boss, a figure of immense responsibility, managed the finances, navigated the route, and maintained discipline among his crew. His decisions could make or break the entire venture.

Yet, like all eras, the golden age of the cattle trails was finite. The very forces that made them possible—the railroads—also contributed to their demise. As rail lines pushed deeper into Texas, it became more efficient and less risky to ship cattle directly from closer points. But the true death knell came with two innovations: barbed wire and the severe winters of 1886-1887. Joseph Glidden’s invention of barbed wire in 1874 allowed farmers to cheaply and effectively fence off their lands, fragmenting the open range into countless private parcels. The vast, uninterrupted stretches of grazing land essential for cattle drives simply ceased to exist.

Then came the "Big Die-Up." The brutal winters of 1886 and 1887, with unprecedented blizzards and temperatures, decimated herds across the plains, particularly in the northern ranges. Millions of cattle froze or starved to death, wiping out the fortunes of many ranchers and signaling the end of the speculative, open-range ranching model. The era of the long cattle drive, a romanticized yet brutal chapter of American history, was effectively over by the late 1880s. The last significant drives on the Great Western Cattle Trail faded into memory around 1889.

The Great Western Cattle Trail, though less celebrated than the Chisholm, remains a powerful symbol of American tenacity and the spirit of the frontier. It represents a brief but pivotal period when the nation truly stretched its legs, pushing the boundaries of what was possible. It’s a legend built on the sweat, courage, and sacrifice of countless cowboys, both celebrated and forgotten.

Today, the physical remnants of the trail are scarce—a rut in the earth, a historical marker, perhaps an old river crossing. But its legacy lives on, deeply embedded in American culture. It is in the enduring image of the cowboy, a figure of rugged independence and quiet strength, that still rides across our movie screens and into our literature. It’s in the songs of the open range, the tales of stampedes, and the romantic notion of a simpler, wilder time. The Great Western Cattle Trail reminds us that America’s legends are not just stories; they are the dust-caked footsteps of those who dared to dream big, transforming a wild frontier into the fabric of a nation, one longhorn at a time. The echo of those thundering hooves, though faint, continues to whisper across the plains, a timeless testament to a defining chapter in the American story.