Dust, Gold, and Gallows: The Enduring Legends of Crime, Punishment, and the Overland Trail in America

America, a nation forged in paradox, has always been captivated by its own origin stories. Among the most potent and enduring are those born from the crucible of westward expansion – tales of desperate journeys, sudden riches, brutal justice, and the audacious defiance of law. These are the legends of the Overland Trail, where the promise of a new life met the stark realities of an untamed frontier, breeding a unique brand of crime and punishment that continues to echo in the American psyche.

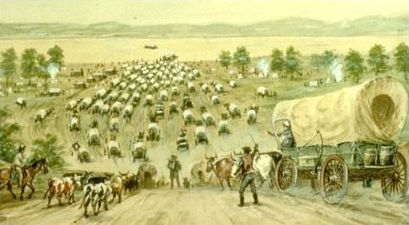

The Overland Trail, a collective term encompassing routes like the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails, was not merely a path across a continent; it was a societal experiment. Between the 1840s and 1860s, an estimated 400,000 to 500,000 people embarked on these arduous treks, leaving behind the established laws and social structures of the East for the vast, unorganized territories of the West. This immense human migration, often driven by the lure of gold in California or fertile lands in Oregon, created a temporary, mobile society where traditional authority was conspicuously absent.

The Crucible of the Trail: Where Law Faltered

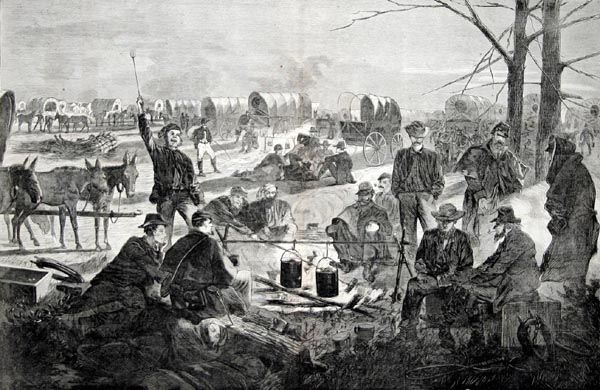

Imagine the scene: thousands of wagons, each a self-contained family unit, stretching for miles across an unforgiving landscape. Days were marked by relentless sun, dust, and the constant creak of wheels; nights by the glow of campfires and the omnipresent threat of the unknown. In this environment, the very conditions for crime were ripe. Resource scarcity, extreme isolation, and the breakdown of traditional social bonds often brought out the worst in human nature.

While the most common dangers were disease, accidents, and environmental hazards, instances of theft, claim jumping, and even murder were not uncommon. Disputes over water, grazing land, or stolen supplies could escalate quickly. Without a formal legal system – no sheriffs, no courts, no jails for hundreds, sometimes thousands, of miles – justice, or its crude approximation, often fell to the travelers themselves.

"The journey itself was a kind of filter," observed historian John D. Unruh Jr. in his seminal work, The Plains Across. "It stripped away the veneer of civilization, revealing both the best and worst of those who dared to undertake it." For the unlucky, this meant encountering individuals who saw the trail’s lawlessness as an opportunity. Bandits and opportunists, sometimes Native American groups defending their lands but often white renegades preying on vulnerable pioneers, posed a constant threat. Reports of wagon trains being raided, livestock stolen, or travelers murdered for their meager possessions were infrequent but terrifying, feeding into the burgeoning mythology of the dangerous frontier.

Outlaws and Anti-Heroes: The Rise of Frontier Crime

As the trails eventually gave way to nascent towns and territories, the scale and notoriety of crime escalated. The influx of wealth from gold rushes, the rapid expansion of railroads, and the sheer volume of unbanked cash circulating in isolated communities created irresistible targets. This was the era that birthed the legendary outlaws of America – figures whose names, though often associated with brutal acts, became intertwined with a romanticized vision of rebellion and freedom.

Jesse James, for instance, a former Confederate bushwhacker, transitioned into a career of bank and train robbery in the post-Civil War era. His gang, including the Younger brothers, terrorized the Midwest, often targeting the very institutions – banks and railroads – that represented the encroaching modern world. To some, especially in the defeated South, James was a latter-day Robin Hood, striking back against corrupt corporations and Yankee sympathizers. To others, he was a cold-blooded killer. His spectacular robberies and daring escapes, meticulously chronicled by sensationalist newspapers, cemented his place as America’s archetypal outlaw. His eventual betrayal and death at the hands of Robert Ford in 1882 only amplified his legend, transforming him from a criminal into a martyr in the popular imagination.

Further west, figures like Billy the Kid, born Henry McCarty, carved out their violent reputations amidst the cattle wars and political feuds of New Mexico. Billy’s short, brutal life, marked by gunfights and escapes, made him a symbol of the untamed frontier. He was pursued relentlessly by Sheriff Pat Garrett, whose eventual killing of the Kid in 1881 became one of the most famous showdowns in Western lore. The sheer youth of "the Kid" – he was barely 21 when he died – added a tragic dimension to his story, ensuring his enduring appeal.

And then there were Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, leaders of the "Wild Bunch," a sophisticated gang that perfected the art of robbing trains and banks across multiple states, from Wyoming to Colorado. Their ability to evade capture for years, often disappearing into the vastness of the West or across the border into Bolivia, painted them as cunning, almost charming rogues. Their legend, further amplified by Hollywood, speaks to a desire for freedom from the constraints of society, a romanticized yearning for the open road, even if it led to violence and ultimately, oblivion.

These outlaws were not merely criminals; they were products of their environment – a society in flux, where law was often weak, and opportunities for honest work were scarce or brutal. Their legends, however, were often crafted by dime novelists and newspaper editors who understood the public’s hunger for dramatic tales of individual daring against overwhelming odds.

Swift and Harsh: The Frontier’s Brand of Justice

Where crime flourished, so too did the desperate need for order. The Overland Trail and the burgeoning frontier towns developed their own unique, often brutal, forms of punishment. With formal legal institutions lagging far behind settlement, justice was frequently dispensed quickly, informally, and with lethal efficiency.

On the trail, disputes were sometimes settled by ad hoc juries of fellow travelers, with punishments ranging from banishment from the wagon train to, in extreme cases, hanging. The most famous example of such frontier justice might be the "hand of God" often invoked in the absence of human law. When formal law arrived, it often did so in the form of dedicated, tough individuals: the frontier marshals and sheriffs.

Figures like Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and Wild Bill Hickok became legends themselves, embodying the thin line between law and lawlessness. Their stories are replete with dramatic shootouts and courageous stands against overwhelming odds. Wyatt Earp’s involvement in the infamous Gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, in 1881, pitted him and his brothers against the Clanton and McLaury factions, a clash that has come to symbolize the struggle for order in a chaotic world. These lawmen were often as quick with a gun as the outlaws they pursued, and their methods, while effective, were far from the due process of modern law.

Beyond individual lawmen, communities frequently resorted to vigilante justice. In places like San Francisco during the Gold Rush, where the influx of people overwhelmed existing legal structures, "Vigilance Committees" formed. These groups, composed of prominent citizens, took the law into their own hands, conducting arrests, trials, and executions with a chilling efficiency. While often successful in quelling lawlessness, their actions were undeniably extra-legal, demonstrating the desperate measures taken when formal government failed to protect its citizens. The Pinkerton National Detective Agency, a private organization, also played a significant role, acting as a quasi-police force for railroads and businesses, their motto "We Never Sleep" becoming synonymous with relentless pursuit.

Punishment on the frontier was often public and deterrent. Lynchings, though horrifying to modern sensibilities, were a grim reality, particularly in communities where legal infrastructure was non-existent or deemed too slow. The sight of a hanging served as a stark warning against crime, a brutal affirmation that even in the wilderness, society would impose its will, albeit through violent means.

The Echoes of Legend

The legends of crime, punishment, and the Overland Trail are more than just historical footnotes; they are foundational myths of the American experience. They speak to a fascination with individualism, the struggle between good and evil, and the enduring allure of the anti-hero. They remind us of a time when the continent was vast and untamed, when law was an aspiration rather than an omnipresent reality, and when personal courage – or depravity – could shape a destiny.

These stories, constantly retold and reinterpreted in books, films, and television, continue to explore fundamental questions: What constitutes justice in a lawless land? How do societies build order from chaos? And what is the true cost of freedom when it borders on anarchy?

From the dusty tracks of the Overland Trail to the iconic showdowns in frontier towns, the intertwined narratives of crime and punishment forged a unique chapter in American history. They are a stark reminder that beneath the veneer of progress and civilization, there often lies a wilder, more primal narrative – a testament to the enduring power of human will, for both good and ill, on the unforgiving stage of the American frontier. These legends, born of dust and blood, continue to shape our understanding of who we are, a nation forever marked by the ghosts of its audacious past.