Dyea, Alaska: Where Dreams Turned to Dust on the Chilkoot Trail

In the wild, untamed expanse of Southeast Alaska, nestled at the head of Lynn Canal, lies a place that whispers tales of fervent ambition, grueling hardship, and the fleeting nature of fortune. Dyea, once a bustling boomtown of thousands, a gateway to the Klondike Gold Rush, is now little more than a collection of skeletal pilings, decaying foundations, and a silent, moss-covered cemetery. It is a ghost town, yes, but one whose spectral presence still pulses with the echoes of a million desperate steps, a testament to the audacious spirit that once fueled the greatest gold stampede in history.

To stand amidst Dyea’s ghostly remains today is to witness nature’s relentless reclamation. Spruce and hemlock trees have swallowed the footprint of what was once a vibrant, chaotic metropolis. The roar of steamship whistles, the clang of hammers, the shouts of prospectors, the bark of dogs – all have been replaced by the rustle of wind through the forest and the cry of gulls over the water. Yet, beneath the serene veneer of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, a vivid history begs to be unearthed, a story of how Dyea briefly became the most important town in Alaska, only to fade into obscurity almost as quickly as it rose.

The Indigenous Gateway: A Trail of Ancient Commerce

Before the feverish scramble for gold transformed the region, the land around Dyea had been a vital artery for centuries. The Chilkoot Trail, beginning near Dyea and winding through the treacherous Coast Mountains, was the exclusive trade route of the Chilkat and Chilkoot Tlingit people. These astute indigenous merchants controlled access to the interior, exchanging coastal goods for furs and other resources with interior Athabascan tribes. Their mastery of the pass, their knowledge of the unforgiving terrain, and their intricate trade networks were the very foundation upon which Dyea’s later, explosive growth would inadvertently build.

The Tlingit understood the Chilkoot Pass not merely as a physical obstacle but as a sacred passage, a source of power and sustenance. Their warnings about its dangers, often dismissed by eager prospectors, would later prove tragically accurate. The trail was their highway, their economy, and their sacred ground long before the first white prospector cast an avaricious eye towards the distant Klondike.

The Golden Spark: From Rumor to Rush

The world changed on July 17, 1897. That day, the steamship Excelsior docked in San Francisco, followed days later by the Portland in Seattle, both carrying prospectors laden with Klondike gold. The news, initially met with skepticism, exploded into an international sensation. "GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!" screamed newspaper headlines. A worldwide economic depression had left many desperate, and the promise of instant riches in the Yukon Territory was an irresistible siren call.

Thousands, then tens of thousands, dropped everything. Farmers left their fields, lawyers abandoned their practices, doctors closed their clinics. They flocked north, drawn by the irresistible lure of the Klondike. But getting to the Klondike was no easy feat. The Yukon lay deep in the Canadian interior, accessible only by arduous routes over towering mountain ranges. Two primary routes emerged from the saltwater fjords of Southeast Alaska: the White Pass Trail, starting from Skagway, and the Chilkoot Trail, starting from Dyea.

Dyea’s Moment in the Sun: The Chilkoot Gateway

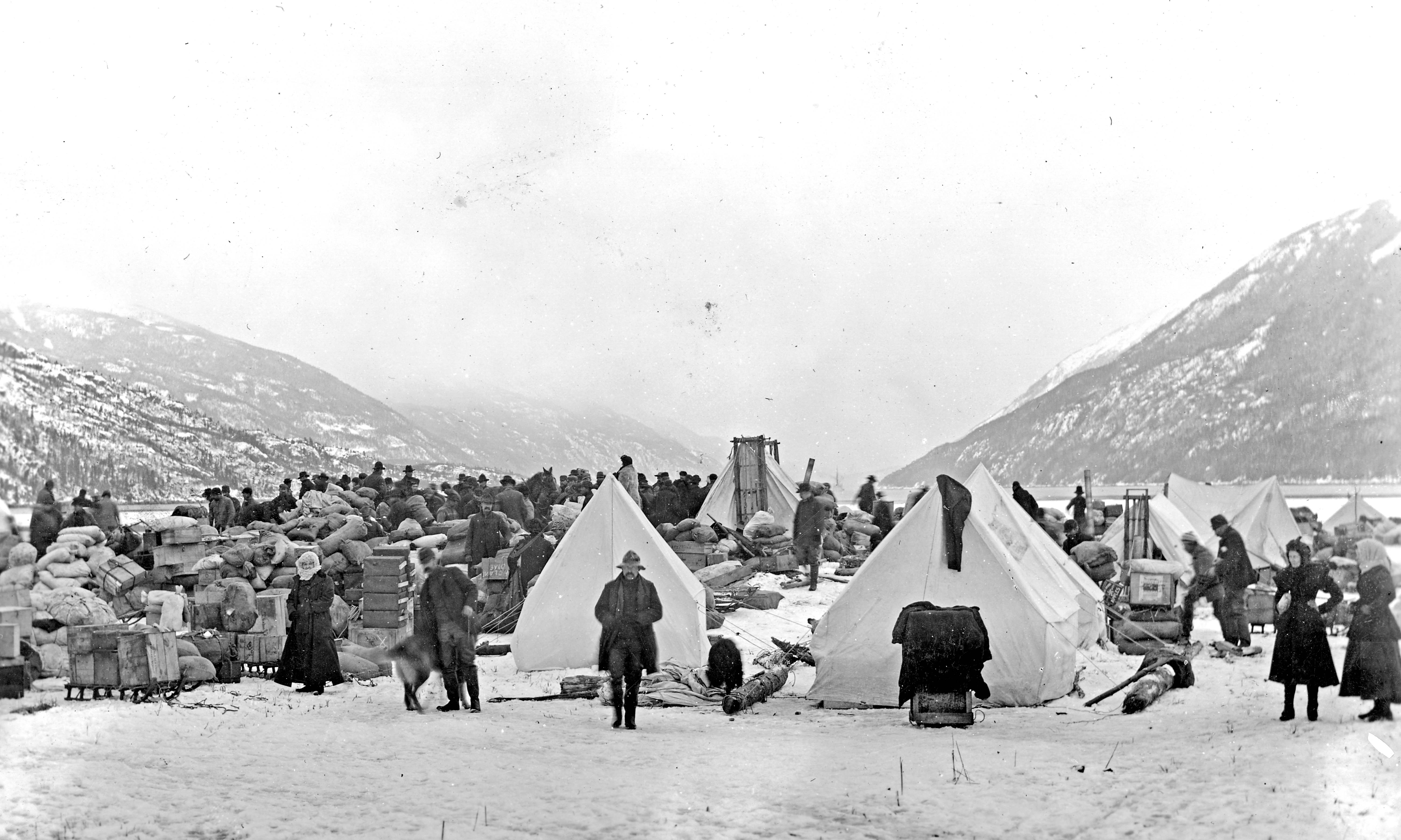

Dyea’s strategic advantage was its proximity to the Chilkoot Trail, historically the most direct and, at the time, perceived as the most navigable route to the Yukon River system. Within months of the gold discovery, Dyea transformed from a sleepy Tlingit fishing camp and a handful of white trading posts into a sprawling boomtown. Its population swelled from a few dozen to an estimated 8,000-10,000 people at its peak in late 1897 and early 1898.

The waterfront became a chaotic jumble of docks, warehouses, and makeshift shanties. Steamships crammed with hopeful prospectors, supplies, and animals jostled for space. "The air was thick with the smell of pine, horse manure, and human sweat," one eyewitness account described. "Every man seemed to be in a hurry, every transaction a desperate gamble."

Dyea’s main street, a muddy thoroughfare, teemed with life. Saloons, hotels, dance halls, general stores, brothels, banks, and assay offices sprang up like mushrooms after a rain. Everything imaginable could be bought, from canned goods and tools to warm clothing and pack animals. Merchants, far from the gold fields, often made their fortunes simply by supplying the gold-seekers. Law enforcement was rudimentary at best, and the town was a hotbed of vice, opportunism, and occasional violence.

The "Ton of Goods" and the Golden Staircase

The Canadian government, wise to the harsh realities of the Arctic wilderness, imposed a strict requirement: every prospector entering the Yukon Territory had to carry a year’s supply of provisions – approximately one ton of goods. This regulation, designed to prevent starvation and maintain order, became the defining challenge of the Chilkoot Trail.

From Dyea, the trail ascended steeply, a mere 33 miles, but miles that would test the limits of human endurance. Prospectors, unable to afford expensive pack horses (which often failed on the steeper sections), or simply choosing to save money, became human pack animals. They would "pack" their ton of goods in stages, moving 50-75 pound loads repeatedly up the trail, often making dozens of round trips. This meant traversing the entire 33 miles potentially 20-30 times, carrying a combined weight of 2,000 pounds.

The most infamous section was the "Golden Staircase," a nearly vertical ascent of 1,500 feet over a mile, often covered in ice and snow. Here, prospectors would cut steps into the frozen face, forming a human chain, slowly inching their way upwards. "The line of men stretched for miles, a black ribbon against the white snow, moving with the agonizing slowness of a glacier," recalled one stampeder. The physical toll was immense, the psychological strain even greater. Many gave up, their dreams crushed by the sheer brutality of the Chilkoot. Yet, thousands persevered, driven by the elusive promise of gold.

The Rivalry and the Railroad’s Betrayal

While Dyea thrived, a fierce rivalry brewed just a few miles down Lynn Canal. Skagway, the starting point for the White Pass Trail, was also booming. The White Pass, though longer and initially even more challenging for pack animals (earning it the moniker "Dead Horse Trail"), offered a critical advantage: it was less steep and more amenable to modern transportation.

This proved to be Dyea’s undoing. In 1898, construction began on the White Pass & Yukon Route railway from Skagway. This ambitious project, blasting through solid rock and scaling the formidable White Pass, represented the future of transportation. For Dyea, whose Chilkoot Trail was too steep and rugged for a conventional railway, it was a death knell.

As sections of the railroad were completed, allowing prospectors and supplies to be transported by train to the interior, the Chilkoot Trail quickly became obsolete. The agonizing multi-trip ascent was replaced by a comfortable, if expensive, train ride. Prospectors, ever practical, abandoned Dyea in droves for the convenience of Skagway.

By the summer of 1899, Dyea was in rapid decline. Businesses shuttered, buildings were abandoned, and the docks lay silent. The population dwindled to a few hundred, then to a mere handful. The dreams that had brought thousands to its muddy streets had evaporated, carried away by the whistle of a train.

The Ghost Town’s Legacy: A Reminder of Fleeting Fortunes

By 1900, Dyea was effectively a ghost town. The great gold rush had largely played out, and what remained of the traffic went through Skagway. Nature, with its slow, inexorable force, began to reclaim what man had briefly wrested from it. Buildings collapsed, docks rotted, and the forest crept in, obscuring the scars of human endeavor.

Today, Dyea is part of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, meticulously preserved not as a reconstructed town, but as an archaeological site and a testament to the past. Visitors can walk along the faint outlines of its former streets, explore the remnants of old buildings, and read interpretive signs that bring the bustling past to life. The Dyea townsite serves as the modern trailhead for those who still dare to tackle the Chilkoot Trail – now a world-renowned backpacking route, attracting adventurers seeking to retrace the steps of the stampeders.

The cemetery, a quiet clearing in the woods, is perhaps the most poignant reminder of Dyea’s brief, intense life. Simple wooden crosses and weathered headstones mark the graves of those who succumbed to disease, accident, or despair, their dreams of gold buried with them in the frozen earth. Each name is a story, a life cut short, a testament to the brutal realities of the gold rush.

Dyea, Alaska, stands as a powerful symbol of the Klondike Gold Rush itself: a sudden, explosive burst of hope and ambition, followed by an equally swift and absolute collapse. It is a cautionary tale of boom and bust, of human endurance pushed to its limits, and of the relentless march of progress that can render an entire town obsolete overnight. Yet, in its quiet solitude, Dyea also celebrates the enduring spirit of adventure, the willingness to risk everything for a dream, no matter how distant or elusive. It reminds us that even in ruin, history whispers, and the echoes of those who passed this way still resonate in the heart of the Alaskan wilderness.