Echoes from the Edge: The Enduring Spirit of the Chimariko Tribe

In the rugged, serpentine canyons of Northwestern California, where the Trinity River carves its path through ancient redwood and fir forests, lies a story both profoundly unique and tragically universal. It is the story of the Chimariko, a Native American tribe whose very existence, let alone their survival, is a testament to an extraordinary resilience. Once numbering perhaps only a few hundred, they were a linguistic island, a cultural enigma, and a people pushed to the absolute precipice of extinction. Yet, from the brink, their echoes persist, whispering tales of a deep connection to the land and an indomitable will to endure.

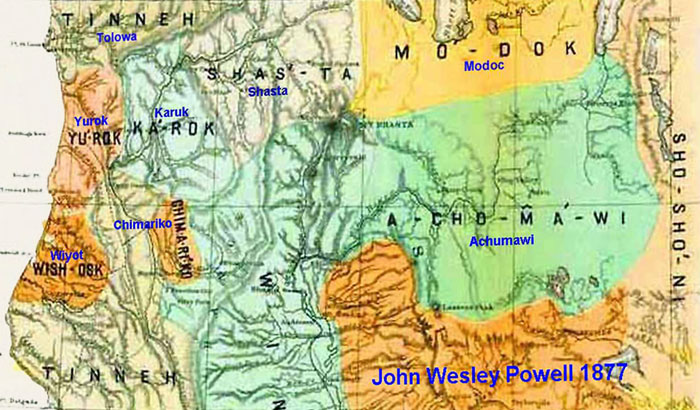

The Chimariko are not widely known, even among those familiar with California’s diverse indigenous tapestry. Their obscurity is, in part, a consequence of their historical isolation and the devastating impact of colonization that nearly erased them from the historical record. Their traditional territory was confined to a relatively small stretch of the Trinity River, primarily around the confluence of the Trinity and New Rivers, a region now part of Trinity County. This geographical remoteness fostered a distinct culture and, most notably, a language so unique it defies classification.

A Linguistic Enigma: The Chimariko Language

Perhaps the most striking feature of the Chimariko people is their language. Chimariko is a linguistic isolate, meaning it has no demonstrable genetic relationship to any other known language family in the world. This stands in stark contrast to most other indigenous languages of California, which often fall into larger families like Hokan, Penutian, or Uto-Aztecan. For linguists, Chimariko has long been a source of fascination and frustration – a puzzle piece that doesn’t fit into any existing framework.

"The Chimariko language represents a unique branch of human linguistic evolution," explains Dr. Lyle Campbell, a leading authority on Native American languages. "Its isolation suggests an incredibly deep history, perhaps representing the linguistic remnant of a much older population stratum in California."

By the early 20th century, the Chimariko language was critically endangered, teetering on the edge of silence. Anthropologists and linguists, recognizing its profound importance, scrambled to document it. Figures like Roland Dixon, Alfred Kroeber, and crucially, J.P. Harrington, spent countless hours working with the last fluent speakers, meticulously recording vocabulary, grammar, and narratives. These efforts, while heroic, were often a race against time, capturing the final breaths of a living tongue. The last known fluent speaker, Sally McLendon, passed away in the 1930s, leaving behind a profound linguistic legacy but also a gaping void in the community. Today, the language is considered extinct in terms of native speakers, though revitalization efforts draw upon the invaluable documentation preserved in archives.

A Life Woven with the Land: Traditional Culture

Before the cataclysmic arrival of Euro-American settlers, the Chimariko lived a life deeply interwoven with the rhythms of their riverine and forest environment. Their existence was one of intimate knowledge of their surroundings, providing sustenance and spiritual connection. Like many California tribes, they were hunter-gatherers, their diet rich in salmon from the Trinity River, deer, elk, and a variety of nuts, berries, and acorns.

Basketry was a highly developed art form, with intricate designs and functional uses for storage, cooking, and gathering. Their social structure was likely organized around kinship groups and villages, with a deep respect for elders and traditional knowledge keepers. Spiritual beliefs centered on a profound reverence for the natural world, understanding the interconnectedness of all living things, and acknowledging the presence of spirits in the landscape. Oral traditions, passed down through generations, conveyed their history, moral codes, and explanations of the world around them.

"Their stories, as far as we’ve been able to reconstruct them, speak of a world alive with meaning," notes Dr. Jan T. Luthin, a scholar of indigenous California cultures. "Every rock, every stream, every animal held a narrative significance, guiding their interactions with their environment and each other." While detailed ethnographic accounts of Chimariko traditional life are sparse due to their rapid decline, the fragments available paint a picture of a resilient and adaptable people, masters of their specific ecological niche.

The Gold Rush: A Cataclysmic Shift

The relative isolation that once protected the Chimariko from external pressures became their undoing with the advent of the California Gold Rush in 1849. The Trinity River region, previously untouched by large-scale Euro-American incursions, became a magnet for thousands of prospectors. This sudden influx of miners, driven by greed and often exhibiting overt hostility, brought with it a swift and brutal wave of destruction.

"The Gold Rush was not just an economic phenomenon; it was an ecological and human catastrophe for California’s indigenous peoples," states historian Albert L. Hurtado. "For tribes like the Chimariko, it meant the almost immediate decimation of their food sources, the invasion of their sacred lands, and an unprecedented onslaught of violence and disease."

Miners dammed and diverted rivers, destroying salmon runs. Forests were clear-cut, disrupting hunting grounds. Perhaps most devastating was the direct violence: massacres, enslavement, and forced displacement became common occurrences. Diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza, to which Native Americans had no immunity, swept through communities, often wiping out entire villages.

The Chimariko, already small in number, were particularly vulnerable. Estimates suggest their population, once numbering in the low hundreds, plummeted to mere dozens by the turn of the 20th century. Survivors were often forced into servitude, assimilated into other tribes, or fled into the most remote corners of their ancestral lands, struggling to maintain their cultural identity amidst overwhelming pressure. The vibrant culture and unique language that had flourished for millennia were pushed to the brink of oblivion in a matter of decades.

Resilience and Reclaiming Identity

Despite the profound losses, the story of the Chimariko is not solely one of tragedy; it is also a powerful narrative of resilience and the quiet, determined struggle for cultural survival. Even after the last fluent speaker passed, descendants of the Chimariko people never forgot their heritage. They maintained connections, albeit often through intermarriage with neighboring tribes like the Hupa, Karuk, and Wintu.

In recent decades, there has been a significant movement among Chimariko descendants to reclaim and revitalize their cultural identity. This includes painstaking efforts to learn about their language from the archived recordings and notes of early linguists. While a full return to fluency is an immense challenge, the act of studying the language, even if only through word lists and grammatical structures, is a profound act of cultural affirmation. It connects current generations to their ancestors and reinforces their unique place in the world.

"Every word we recover, every phrase we learn, is like bringing a piece of our history back to life," says a descendant involved in language revitalization efforts, who preferred not to be named, emphasizing the communal nature of the work. "It’s not just about speaking; it’s about understanding how our ancestors thought, how they saw the world."

Beyond language, contemporary Chimariko descendants are also working to revive traditional practices, arts, and spiritual understandings. This includes basket weaving, traditional ecological knowledge, and engaging in cultural gatherings that reinforce community bonds. They participate in broader inter-tribal initiatives for cultural preservation and advocate for their rights and recognition. While they do not have a federally recognized tribal government, their identity as Chimariko endures through family lines and a shared commitment to their heritage.

A Future Woven from the Past

The Chimariko story serves as a poignant microcosm of the broader indigenous experience in California and across the Americas. It highlights the devastating impact of colonization, the near-erasure of unique cultures, and the incredible strength required to survive such historical traumas. Yet, it also offers a glimmer of hope: that even when a language falls silent and a population dwindles to a whisper, the spirit of a people can persist.

The challenges remain formidable. Issues of land rights, poverty, and the ongoing struggle against historical erasure continue to affect indigenous communities. For the Chimariko, the fight for recognition and resources to sustain their revitalization efforts is an ongoing journey.

As the Trinity River continues its timeless flow, carrying the echoes of millennia, the descendants of the Chimariko tribe stand as living testaments to an unbroken chain. Their quiet determination to reclaim their heritage, to speak the fragments of a language once thought lost, and to honor their ancestors is a powerful reminder that culture is not static, and identity, though challenged, can never be truly extinguished. Their story is a vital chapter in the ongoing narrative of survival, resilience, and the enduring power of the human spirit.