Echoes from the Ice Age: The Enduring Mystery of the Clovis Culture

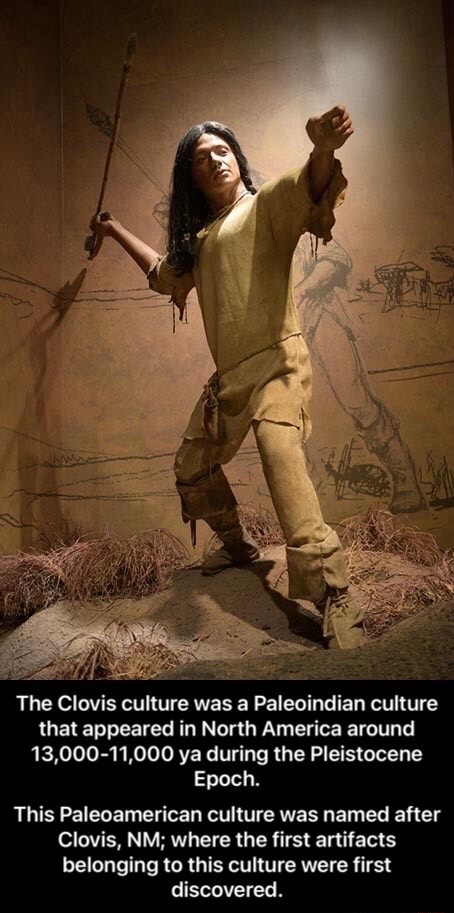

Imagine a vast, untamed North America, some 13,000 years ago. Glaciers still clung to the northern reaches, but a corridor of ice-free land stretched south, a gateway to a continent brimming with colossal beasts – mammoths, mastodons, giant bison, and saber-toothed cats. Into this prehistoric arena stepped a people whose ingenuity and adaptability would leave an indelible mark on the archaeological record: the Clovis culture. For decades, they were celebrated as the continent’s first pioneers, the trailblazers who charted humanity’s initial course into the Americas. Yet, like the glaciers that shaped their world, the understanding of Clovis has proven to be a dynamic and shifting landscape, constantly reshaped by new discoveries and evolving theories.

The story of Clovis begins, quite literally, with a point. Not just any point, but a remarkably crafted, bi-facially flaked stone projectile point, typically 3 to 5 inches long, characterized by a distinctive "flute" or channel removed from the base on both faces. This flute allowed the point to be securely hafted onto a spear shaft, creating a deadly weapon capable of piercing the thick hides of megafauna. These iconic Clovis points, often made from high-quality chert, obsidian, or jasper, are an unmistakable signature, found across a vast swathe of North America, from New England to the Pacific Northwest, and as far south as Central America.

The discovery of these points in association with extinct megafauna in Blackwater Draw, New Mexico, in the 1930s, alongside subsequent finds at other sites like the Dent site in Colorado (where points were found with mammoth skeletons), cemented the idea of the "Clovis First" paradigm. This theory proposed that the Clovis people were the initial human inhabitants of the Americas, arriving via the Bering land bridge (Beringia) from Asia around 13,500 to 13,000 years ago (calibrated radiocarbon years). They were envisioned as highly mobile, big-game hunters, rapidly spreading across the continent, their distinctive technology allowing them to thrive in diverse environments.

For a long time, the "Clovis First" model was almost archaeological dogma. The widespread distribution of Clovis points, their consistent dating, and the apparent absence of older, unambiguous archaeological sites provided a compelling, straightforward narrative. "The elegance of the Clovis First model was its simplicity," explains Dr. Melinda Smith, an archaeologist specializing in early American cultures. "One wave of people, one unique technology, one path of dispersal. It fit the evidence we had at the time perfectly." This narrative painted a picture of a single, highly successful cultural group, mastering their environment with a sophisticated tool kit, colonizing an empty continent with remarkable speed. Their ability to hunt megafauna, particularly mammoths, was seen as a key to their success, providing ample resources for their nomadic lifestyle.

However, the beauty of archaeology lies in its constant evolution, its willingness to challenge established truths in the face of new data. Over the past few decades, the solid foundations of the "Clovis First" paradigm have begun to show cracks, eventually giving way to a more complex and nuanced understanding of the peopling of the Americas. The first significant challenges emerged from sites that presented evidence of human occupation before the accepted Clovis timeline.

One of the most pivotal sites in this paradigm shift is Monte Verde in Chile. Excavated by Tom Dillehay and his team, Monte Verde revealed remarkably preserved evidence of a human settlement dating back approximately 14,500 years ago – a full millennium before the earliest accepted Clovis sites. The site yielded wooden structures, tools, medicinal plants, and even mastodon meat, all preserved in a peat bog. The initial skepticism surrounding Monte Verde was immense, but after rigorous review by a panel of leading archaeologists in 1997, its pre-Clovis age was widely accepted, effectively dismantling the "Clovis First" wall. "Monte Verde forced us to confront the uncomfortable truth that our timeline was wrong," Dillehay noted in an interview, "It was a game-changer, opening up entirely new possibilities for how and when people arrived."

Since Monte Verde, other pre-Clovis sites have emerged, further bolstering the argument for an earlier human presence. The Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania, for instance, has yielded evidence of human occupation dating back as far as 16,000 years ago, though its earliest levels remain a subject of debate among some scholars due to the challenges of dating. More recently, sites like the Paisley Caves in Oregon have provided compelling evidence of human presence around 14,300 years ago, not through stone tools but through coprolites (fossilized feces) containing human DNA, alongside extinct camel and horse bones. The Gault Site in Texas, while a rich Clovis site, also contains clear evidence of pre-Clovis occupation, including distinct tool types beneath the Clovis layers, pushing back the local timeline.

These discoveries have led to a complete re-evaluation of the peopling of the Americas. The Bering land bridge, while still a viable route, is no longer considered the only or even the primary path. The "coastal migration theory" has gained significant traction. This hypothesis suggests that early peoples, adapted to marine environments, followed the "kelp highway" along the Pacific coast of North America, using boats or other watercraft. This route would have offered abundant resources, such as fish, shellfish, and marine mammals, and would have been accessible even when interior land routes were blocked by glaciers. Genetic evidence from modern Indigenous populations, showing closer ties to specific Asian groups and patterns of genetic diversification that align with a rapid coastal spread, further supports this theory.

The decline and eventual disappearance of the distinct Clovis culture around 12,900 years ago is another fascinating puzzle. This period coincides with a dramatic climatic event known as the Younger Dryas, a sudden return to near-glacial conditions that plunged parts of the Northern Hemisphere back into an ice age for over a thousand years. This rapid cooling would have severely impacted the ecosystems that Clovis people relied upon, potentially leading to a decline in megafauna populations. While the exact cause of the megafauna extinction remains debated – a combination of climate change, human overhunting (the "overkill hypothesis"), and perhaps even a cometary impact event – it is clear that the world of the Clovis people was undergoing profound transformations.

The disappearance of Clovis as a distinct archaeological culture does not mean the people vanished. Instead, it is more likely that they adapted, diversified, and evolved into the myriad post-Clovis cultures that subsequently flourished across North America. Their iconic fluted points gave way to a wider array of projectile point styles, reflecting regional adaptations and innovations. The descendants of Clovis, alongside those who arrived earlier, formed the foundation of the continent’s rich and diverse Indigenous heritage.

Today, the Clovis culture stands as a testament to human ingenuity and resilience, not as the "first" Americans, but as one of the earliest and most distinctive cultural expressions in the continent’s deep history. Their ability to craft advanced tools, navigate vast landscapes, and hunt formidable prey remains a remarkable achievement. The ongoing archaeological quest to understand Clovis, and the broader narrative of the peopling of the Americas, continues to push the boundaries of our knowledge, challenging assumptions and revealing the incredible complexity of our shared human journey. Every new dig, every unearthed artifact, every piece of genetic evidence adds another layer to this captivating story, reminding us that the past is never truly settled, always waiting for another echo from the Ice Age to reveal its secrets.