Echoes in Adobe: Unearthing the Complex Legacy of California’s Missions

For generations, the California Missions have occupied a cherished, almost mythical space in the Golden State’s collective consciousness. Their red-tiled roofs, whitewashed adobe walls, and tranquil courtyards evoke images of serene spiritual havens, pioneering resilience, and a romanticized genesis for what would become a global economic powerhouse. Schoolchildren across California build sugar cube replicas, and tourists flock to their hallowed grounds, often perceiving them as quaint historical landmarks.

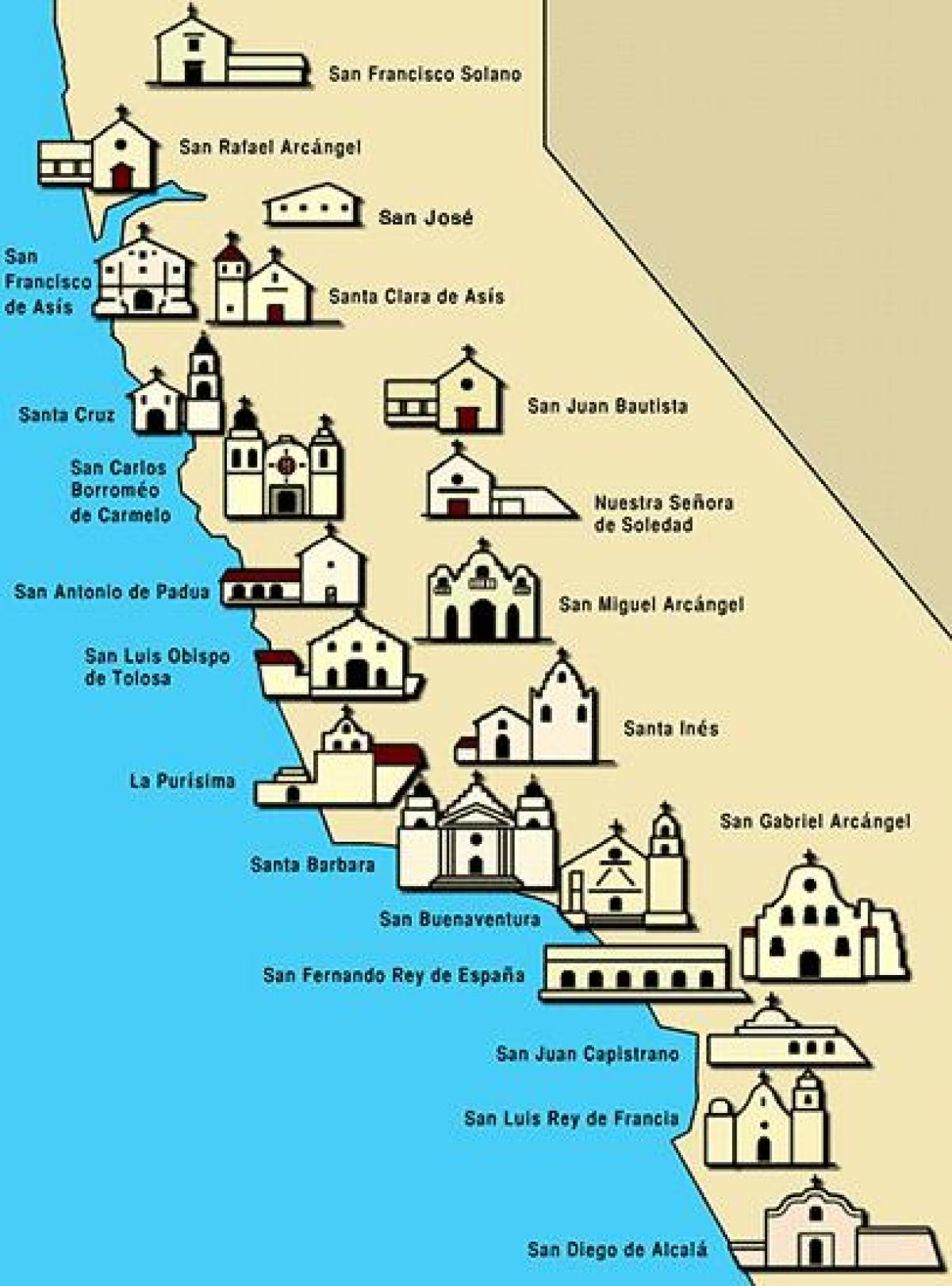

But behind the sun-drenched facades and carefully manicured gardens lies a far more complex, often painful, and fiercely debated history. The 21 missions, strung along El Camino Real like a string of pearls from San Diego to Sonoma, are not merely architectural relics; they are living testaments to a brutal collision of cultures, a crucible of forced assimilation, and the enduring legacy of Spanish colonialism that shaped California irrevocably. To truly understand these iconic structures is to peel back layers of myth and confront the uncomfortable truths of their origins and impact.

The Spanish Imperative: God, Gold, and Geopolitics

The story of the California Missions begins not with spiritual enlightenment alone, but with the pragmatic ambitions of the Spanish Empire. By the mid-18th century, Spain’s hold on its vast American territories was being challenged. Rumors of Russian encroachment from the north (via Alaska and the Pacific Northwest) and the growing presence of other European powers spurred a desperate need to solidify its claim on Alta California, a territory largely unexplored and populated by hundreds of diverse indigenous nations.

The strategy was tripartite: presidios (military forts) for defense, pueblos (civilian towns) for settlement, and missions for evangelization and the "civilizing" of the native population. The Franciscan friars, led by the indefatigable Father Junípero Serra, were the spearhead of this expansion. Serra, a diminutive but iron-willed man, arrived in 1769, establishing Mission San Diego de Alcalá, the first of the 21 missions. His zeal was unquestionable; his methods, however, are the subject of intense modern scrutiny.

Serra and his fellow Franciscans believed they were saving "heathen" souls by bringing them into the fold of Catholicism and Spanish colonial society. Their vision was to transform hunter-gatherer societies into sedentary agricultural communities, teaching them Spanish language, crafts, and farming techniques. "The missions were not merely churches," notes Dr. Elena Rodriguez, a historian specializing in California Native American studies. "They were comprehensive economic and social units, designed to be self-sufficient and to serve as centers of Spanish control."

A Forced Utopia: The Indigenous Experience

For the estimated 300,000 Native Americans living in California prior to European contact, the arrival of the Spanish heralded an unprecedented catastrophe. They were not "empty lands" waiting to be discovered, but vibrant, complex societies with sophisticated ecological knowledge, rich spiritual traditions, and diverse languages. From the Kumeyaay in the south to the Ohlone, Chumash, and Miwok in the central and northern regions, these peoples had thrived for millennia.

The missions, however, dismantled this ancient way of life. Native Americans, often lured by promises of food and protection during times of drought or inter-tribal conflict, or forcibly rounded up by Spanish soldiers, were brought into the mission system. Once baptized, they were known as neophytes and were forbidden from leaving. Their traditional religions and languages were suppressed, replaced by Catholic dogma and Spanish. They were forced to labor in fields, construct buildings, weave textiles, and tend livestock, all under the strict supervision of the friars and soldiers.

Life in the missions was harsh. Punishments for perceived transgressions – attempting to flee, practicing traditional ceremonies, or failing to meet work quotas – ranged from flogging to imprisonment. More devastating than any physical punishment, however, was disease. Native Americans had no immunity to European illnesses like smallpox, measles, and influenza. Overcrowded and unsanitary mission conditions became breeding grounds for epidemics. The demographic collapse was staggering: the native population in the mission areas plummeted from an estimated 150,000 in 1769 to just 15,000 by 1832, a decline of 90%.

"My ancestors were survivors," states Manuel Reyes, a descendant of the Ohlone people whose ancestors were at Mission San Juan Bautista. "But the missions took everything – our land, our language, our spiritual connection to the earth, and tragically, so many lives. To call them places of salvation ignores the immense suffering."

Architectural Resilience and Economic Powerhouses

Despite the human cost, the missions were undeniably feats of engineering and organization. Built largely by indigenous labor, often under duress, using local materials like adobe bricks, timber, and fired clay tiles, they stand as enduring monuments to a particular architectural style. Each mission typically featured a church, living quarters for friars, workshops, storerooms, and agricultural fields. They were designed to be self-sufficient and, indeed, became the economic powerhouses of Alta California, producing vast quantities of grain, wine, olive oil, cattle hides, and tallow.

The iconic red tile roofs, often seen as quintessentially Californian, were a practical innovation, offering better protection against rain and fire than traditional thatched roofs. The thick adobe walls provided insulation against the region’s temperature extremes. Many missions boast impressive bell towers, elaborate altars, and beautiful frescoes, again, often created by indigenous artisans whose traditional artistic skills were adapted to European forms.

Secularization, Decline, and Romantic Revival

The mission era lasted just over 60 years. Following Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821, the new government viewed the missions as vestiges of colonial power and a hindrance to economic development. In 1833-34, the Mexican government enacted secularization laws, intending to redistribute mission lands to the neophytes and other Mexican citizens.

In practice, this often led to chaos and further disenfranchisement for Native Americans. Mission lands and assets were frequently seized by wealthy Californios (Mexican settlers) or fell into disrepair. The indigenous population, often lacking land titles, resources, and protection, scattered or were forced into servitude on private ranches. By the time California became part of the United States in 1848, many missions were crumbling ruins.

The mid-19th century saw little interest in their preservation. It wasn’t until the late 1800s that a romanticized view of the missions began to emerge. Writers like Helen Hunt Jackson, whose influential 1884 novel Ramona depicted a tragic love story set against the backdrop of mission life, sparked a wave of nostalgia. While Jackson was also a fierce advocate for Native American rights (her earlier work, A Century of Dishonor, exposed U.S. government injustices), Ramona inadvertently contributed to the myth of the missions as idyllic, benevolent institutions.

This romantic revival fueled the "Mission Revival" architectural movement and led to significant restoration efforts in the early 20th century, often driven by organizations like the California Landmarks Club. These restorations, while preserving the physical structures, frequently prioritized aesthetic appeal over historical accuracy, sometimes erasing evidence of indigenous construction or later modifications.

The Ongoing Dialogue: Reconciliation and Reinterpretation

Today, the California Missions remain powerful, often contradictory, symbols. They are popular tourist destinations, active Catholic parishes, and vital educational sites. Yet, they are also battlegrounds in a fierce debate over historical memory, cultural appropriation, and the ongoing struggle for Native American recognition and justice.

The 2015 canonization of Father Junípero Serra by Pope Francis ignited a firestorm of protest. While the Vatican hailed Serra as a saintly evangelist, many Native American groups and their allies condemned the act, arguing it glorified a figure responsible for immense suffering and cultural destruction. Statues of Serra have been toppled or defaced in recent years, a stark manifestation of this unresolved tension.

"The missions represent a legacy of trauma for our people," says Reyes. "We are not asking for them to be torn down, but for the full truth to be told. For the stories of our ancestors, their resilience, and their suffering to be central, not just an afterthought."

Many missions are now making efforts to incorporate more indigenous perspectives into their exhibits, acknowledging the forced labor and devastating impact. Some are working with tribal communities on repatriation of ancestral remains and artifacts. This shift reflects a broader societal movement towards decolonizing history and giving voice to previously marginalized narratives.

The California Missions are more than mere relics; they are living testaments to the complex, often brutal, and deeply intertwined history of California. They embody the conflicting ideals of faith and conquest, the clash of civilizations, and the enduring resilience of indigenous peoples. As California continues to grapple with its past, the missions stand as a potent reminder that history is rarely simple, and understanding it fully requires confronting its uncomfortable truths, listening to all its voices, and committing to an ongoing dialogue of reconciliation and reinterpretation. Only then can these adobe walls truly echo with the full story of the Golden State’s origins.