Echoes in the Adobe: Unearthing the Enduring Legacy of Tumacácori Mission

The Arizona sun, a relentless artist, paints the ancient adobe walls of Tumacácori Mission in hues of ochre and rust, casting long, dramatic shadows across the dusty ground. Here, amidst the quiet hum of the Sonoran Desert, stands a sentinel of history – a place where cultures collided, faiths intertwined, and a new world was forged on the ashes of the old. Tumacácori National Historical Park, a testament to endurance and a crucible of human stories, is far more than just a picturesque ruin; it is a living classroom, an open book etched in stone and mud, waiting to tell tales of missionaries, indigenous resilience, and the relentless march of time.

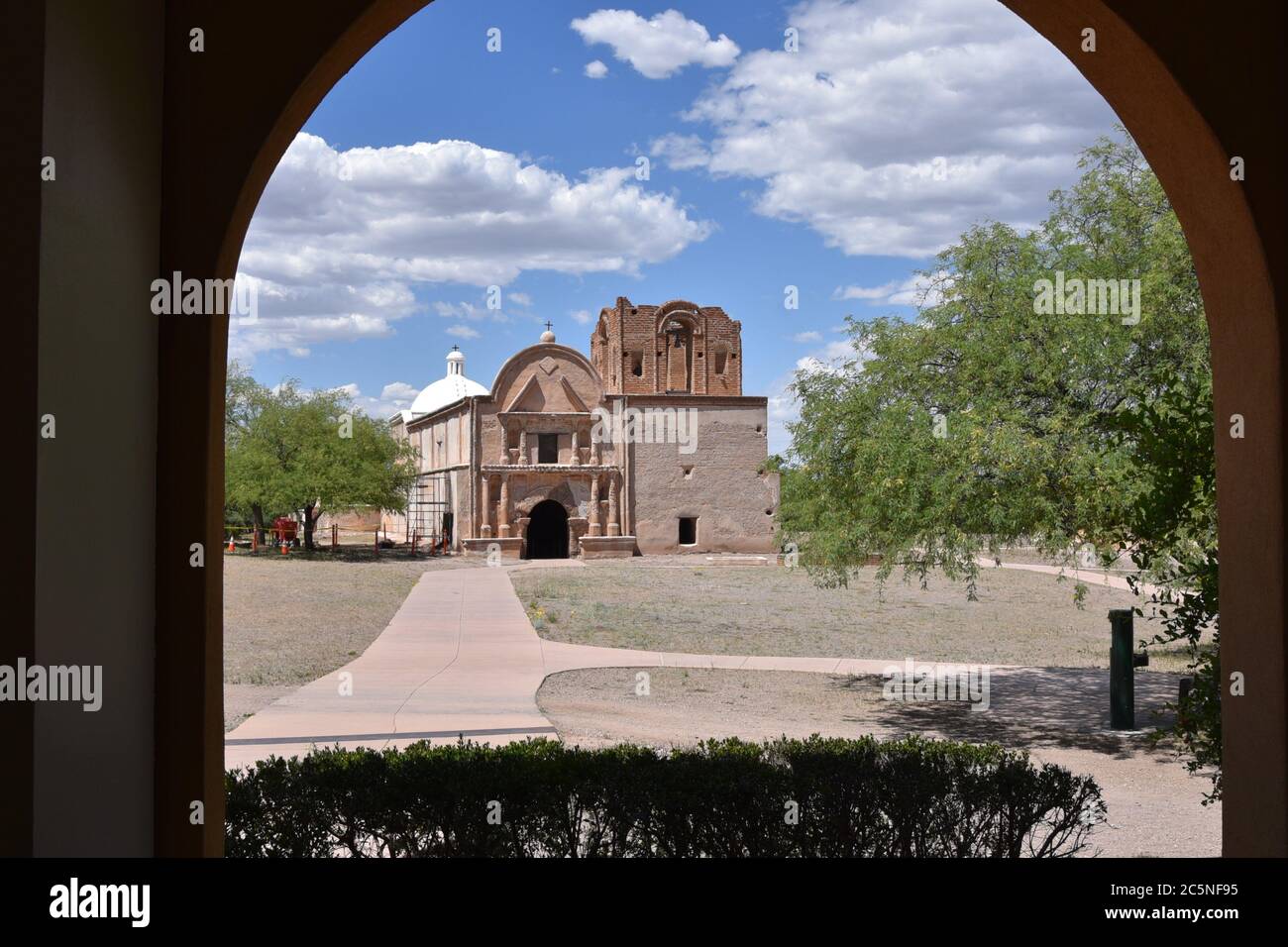

To walk through the arched gateway into the mission grounds is to step back centuries. The air, thick with the scent of creosote and old earth, seems to hum with the echoes of Spanish hymns, the murmur of O’odham prayers, and the distant hoofbeats of colonial horses. This isn’t merely a site of historical interest; it’s a profound journey into the heart of the Spanish colonial frontier, a place where the grand ambitions of empire met the stark realities of the desert and the deep-rooted cultures of its native inhabitants.

The Genesis: Black Robes and Ancient Lands

The story of Tumacácori begins long before the impressive church structure we see today. It started in the late 17th century with the arrival of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, a charismatic Jesuit missionary whose vision stretched across the vast, unexplored territory then known as Pimería Alta. Kino, often called the "Black Robe," was an explorer, cartographer, and evangelist who established a chain of missions and visitas (visiting stations) along the Santa Cruz River Valley. His aim was to convert the indigenous O’odham people (often referred to as Pima by the Spanish) to Christianity, and to introduce European farming techniques and livestock.

In 1691, Kino established the first visita at a site known to the O’odham as "Tu-Ma-Ka-Kor," meaning "the place of the flat-nosed one" or "rocky place," which would later be Hispanized to Tumacácori. This initial settlement, San Cayetano de Tumacácori, was not the grand edifice we see today, but a humble chapel and dwelling built of perishable materials. The O’odham, who had long cultivated crops like corn, beans, and squash along the fertile banks of the Santa Cruz River, were initially receptive, seeing potential benefits in the new agricultural methods and goods the Spanish brought.

However, the exchange was far from one-sided. The Spanish brought not only faith and farming but also disease and demands for labor. The colonial project, though often framed by missionaries as salvation, inherently disrupted traditional ways of life. This tension simmered beneath the surface, occasionally boiling over into open conflict, most notably during the Pima Revolt of 1751, which saw several missionaries and Spanish settlers killed. Tumacácori itself was briefly abandoned and then re-established a few miles north of its original location, at the site of the current mission.

The Franciscan Era: Ambition in Adobe

The year 1767 marked a pivotal shift when King Charles III of Spain, suspicious of the Jesuits’ growing power, expelled them from all Spanish territories. The Franciscans, another mendicant order, stepped in to take over the missions of Pimería Alta. It was under their stewardship, particularly from the late 18th century into the early 19th, that the monumental church building we admire today began to take shape.

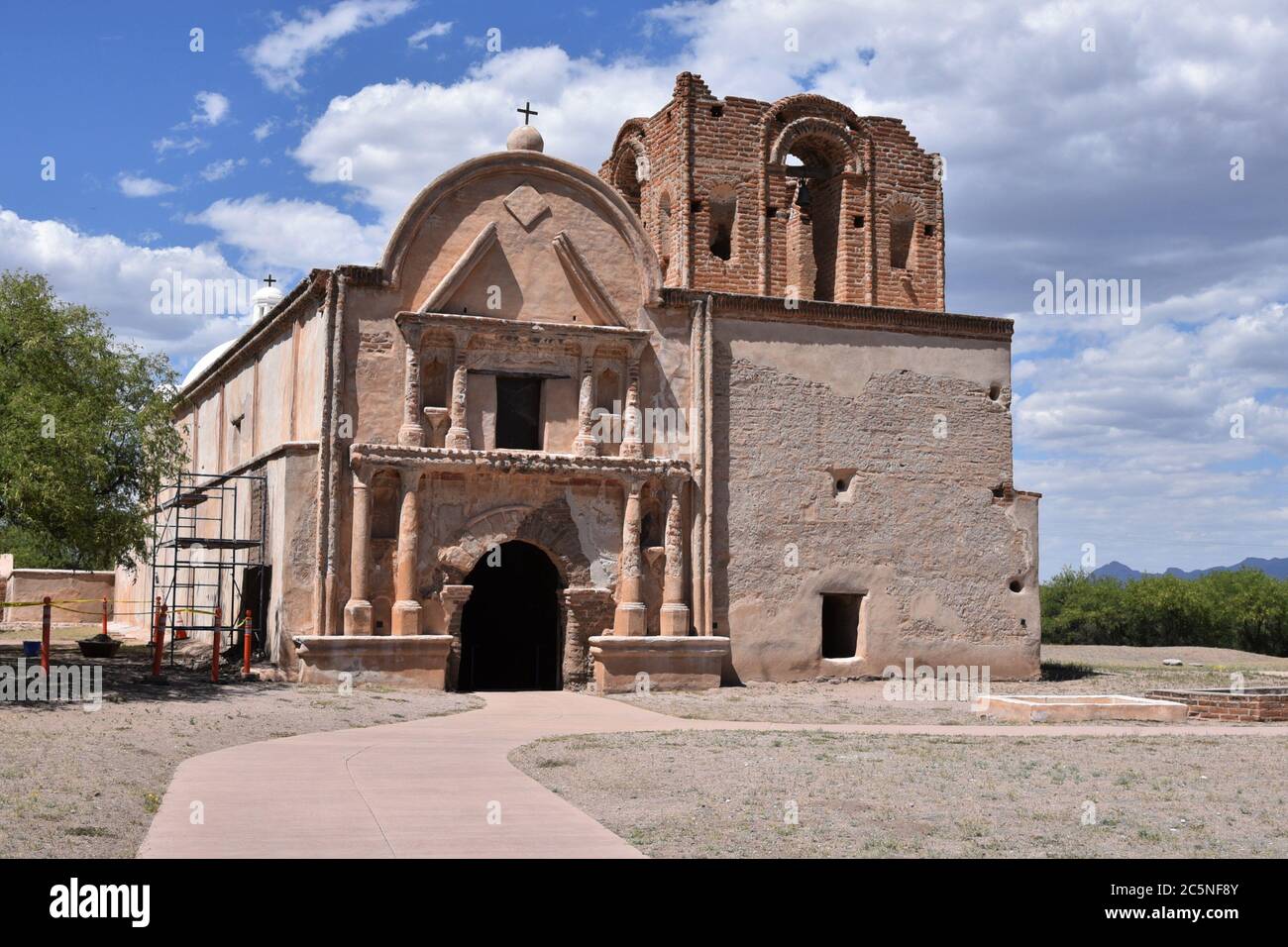

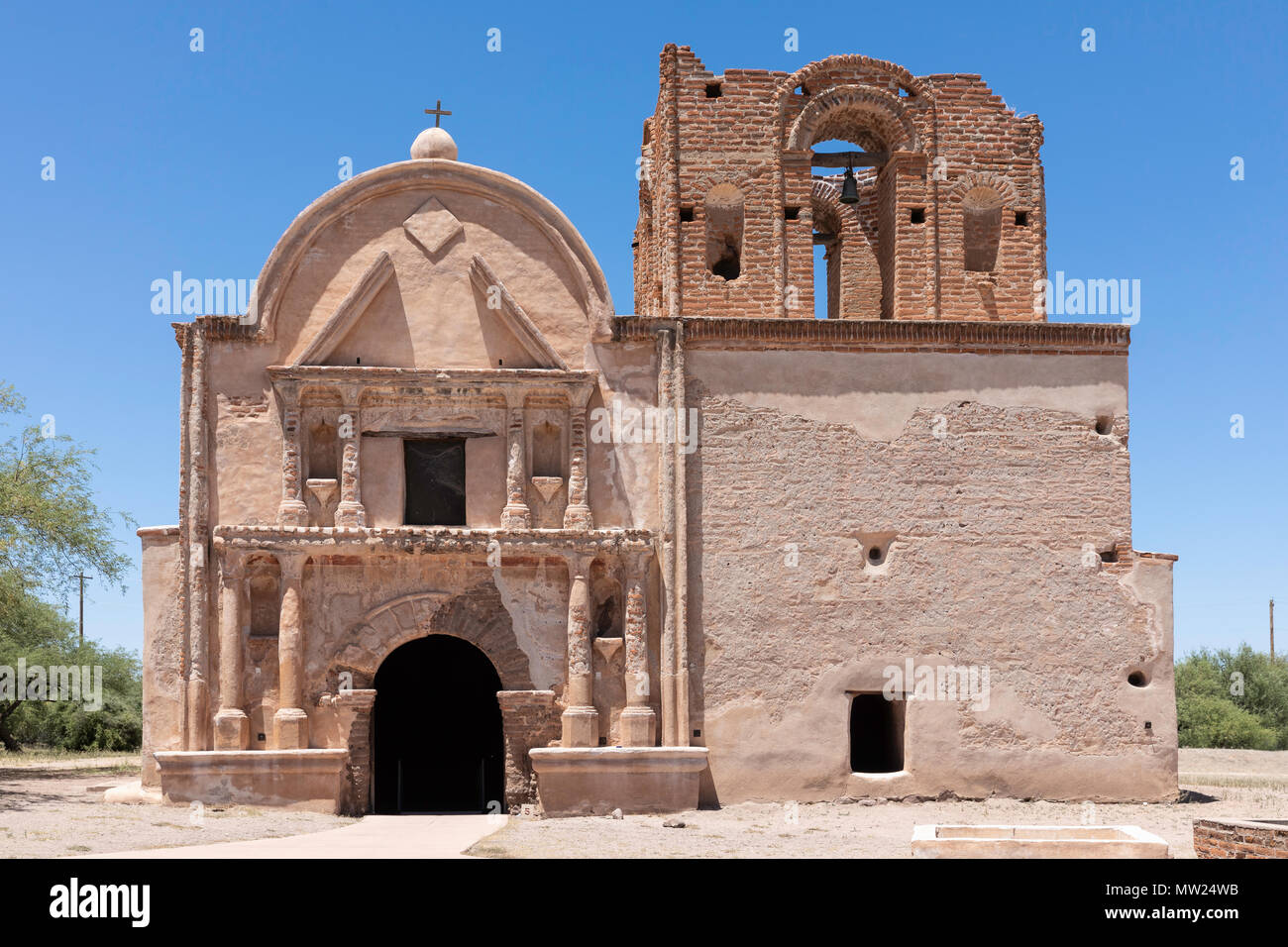

Friar Narciso Gutiérrez initiated the construction of the current church around 1800. This was an ambitious undertaking, especially for a remote frontier outpost. The church was designed in the elegant, if somewhat restrained, Baroque style common to mission architecture, featuring a grand façade, a soaring dome over the sanctuary, and an imposing bell tower that was never fully completed.

"The architecture itself tells a story of aspiration and limitation," explains Maria Sanchez, a park ranger and historian at Tumacácori. "They were trying to replicate the grand cathedrals of Spain in a desert outpost, using local materials and indigenous labor. The unfinished bell tower, for instance, isn’t a sign of failure, but a testament to the harsh realities of the frontier – constant Apache raids, dwindling resources, and political instability."

The mission compound became a vibrant, if tightly controlled, community. Indigenous neophytes lived and worked within its walls, learning European crafts like carpentry, weaving, and blacksmithing, alongside religious instruction. They tended fields, raised livestock, and built the very structures that housed them. The mission’s self-sufficiency was vital, as it lay along El Camino Real, "The Royal Road," a crucial supply route connecting Mexico City to the northernmost outposts of New Spain.

Abandonment and Decay: The Desert Reclaims Its Own

The early 19th century brought a new wave of turmoil. Mexico’s War of Independence from Spain (1810-1821) severed the lifeline of support and protection that the missions had relied upon. The newly independent Mexican government, grappling with its own internal struggles, had little interest or resources to dedicate to distant frontier missions. In 1828, a decree secularized all missions, effectively stripping them of their religious authority and communal lands.

Without the padres and the Spanish military presence, Tumacácori became increasingly vulnerable. Apache raids, a persistent threat throughout the colonial period, intensified. The O’odham population, decimated by disease and cultural disruption, dwindled, and many sought refuge in more secure areas. By the mid-1840s, Tumacácori Mission was effectively abandoned. Its magnificent adobe walls, once echoing with prayers and industry, fell silent, left to the mercy of the elements.

The desert, which had reluctantly yielded to the mission’s construction, slowly began to reclaim it. Wind and rain eroded the adobe, and vegetation took root in cracks and crevices. Accounts from American travelers and explorers after the Gadsden Purchase of 1854, which brought the region into U.S. territory, paint a picture of a romantic ruin, a ghost of its former glory. J. Ross Browne, an artist and writer who visited in the 1860s, described it as "a magnificent temple, now crumbling into ruin, and surrounded by a few decayed huts."

Preservation and Reconciliation: A National Treasure

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw growing recognition of Tumacácori’s historical significance. Early preservation efforts began, culminating in its designation as a National Monument by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908. This marked a turning point, safeguarding the mission from further decay and ensuring its protection for future generations. In 1990, its status was elevated to a National Historical Park, reflecting its broader importance not just as a mission, but as a site encompassing multiple cultural layers and historical narratives.

Today, the National Park Service meticulously cares for Tumacácori. Stabilization projects ensure the integrity of the fragile adobe, while archaeological digs continue to unearth secrets from beneath the earth. The park also strives to tell a more complete, nuanced story, one that moves beyond a purely European-centric view. The voices of the O’odham, Yaqui, and other indigenous peoples who lived and labored here are central to the interpretation, acknowledging both the spiritual solace found by some and the cultural trauma experienced by others.

"Tumacácori is a powerful place because it forces us to confront the complexities of history," says Dr. Robert Johnson, a historian specializing in the American Southwest. "It’s not a simple narrative of good versus evil, but a deeply human story of ambition, faith, resistance, and adaptation. Understanding Tumacácori helps us understand the very foundations of the American Southwest and the enduring impact of colonial encounters."

The park’s museum offers a deeper dive into these narratives, displaying artifacts, maps, and interpretive exhibits that illuminate the lives of all who called this place home. Beyond the main mission church, visitors can explore the ruins of the older San Cayetano de Tumacácori site and the nearby mission of Guevavi, adding layers to the understanding of the mission chain.

Tumacácori Today: A Bridge to the Past

Tumacácori National Historical Park is more than just a collection of old buildings; it’s a vibrant space that fosters cultural exchange and understanding. Annually, it hosts La Fiesta de Tumacácori, a colorful celebration of the diverse cultures of the Santa Cruz Valley, featuring music, dance, traditional crafts, and food from O’odham, Yaqui, Mexican, and Anglo traditions. This event beautifully embodies the park’s mission to connect the past with the present, and to celebrate the shared heritage of the borderlands.

As the sun dips below the horizon, painting the sky in fiery oranges and purples, the silence returns to Tumacácori. The mission stands, solid and stoic, a silent witness to centuries of human endeavor. It is a place of profound beauty and poignant lessons, reminding us that history is not a static collection of facts, but a dynamic, unfolding story of interconnected lives. Tumacácori beckons, inviting all who visit to listen closely to the echoes in the adobe, and to ponder the enduring legacy of a place where worlds met, and continue to resonate, across time.