Echoes in the Canyons: The Enduring Mystery of Carbon County’s Ghost Towns

The wind, a constant sculptor of Utah’s rugged landscape, whispers through empty window frames and rust-eaten machinery in Carbon County. It carries not just the scent of sagebrush and red dust, but the faint, persistent echoes of lives lived, fortunes sought, and dreams abandoned. This is a land shaped by coal, a black gold that fueled a nation and, in turn, birthed a constellation of vibrant, if fleeting, communities. Today, many of these once-bustling towns stand as silent sentinels, their skeletal remains a haunting testament to the boom-and-bust cycles of the American West.

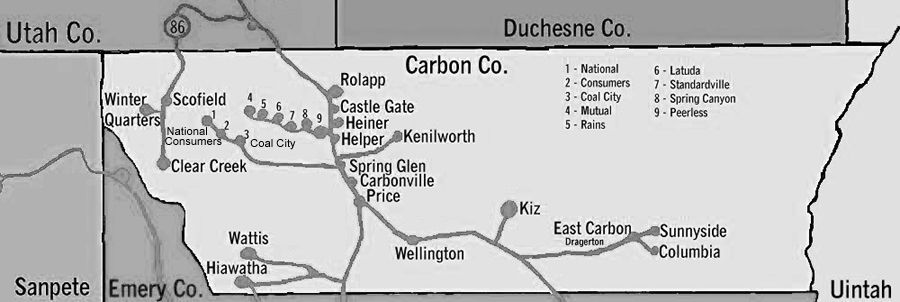

Carbon County, named for the vast coal deposits beneath its surface, was a crucible of industry and human endeavor. From the late 19th century through the mid-20th, its canyons and mesas teemed with miners, railroad workers, and their families, drawn by the promise of steady work and a better life. Immigrants from across Europe – Greeks, Italians, Slavs, Finns, Welsh – alongside Japanese and Mexican laborers, forged a diverse, resilient society in a harsh, unforgiving environment. They built homes, schools, churches, and company stores, transforming barren landscapes into thriving, albeit often isolated, bastions of industry.

But the very forces that gave life to these towns – the insatiable demand for coal and the whims of the market – would ultimately seal their fate. The stories of Carbon County’s ghost towns are not merely tales of abandonment; they are poignant narratives of human resilience, catastrophic tragedy, technological advancement, and the relentless march of economic change.

The Rise and Fall: A Symphony of Coal and Iron

The genesis of Carbon County’s towns was inextricably linked to the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad. As the railroad snaked its way through the formidable canyons of eastern Utah in the 1880s, it unearthed vast seams of high-quality coal, essential for fueling locomotives and smelting operations. This discovery sparked a frenzied period of development. Towns like Winter Quarters, nestled high in the mountains, became some of the earliest and most productive coal camps.

Winter Quarters, however, would also become the site of one of Utah’s most devastating industrial disasters. On May 1, 1900, a massive explosion ripped through the mines, killing at least 200 men, many of them Finnish and Italian immigrants. The disaster left entire families decimated and cast a long shadow over the nascent coal industry. Though the mine eventually reopened, the tragedy profoundly impacted the community. Today, little remains of Winter Quarters beyond a cemetery where the victims lie, their headstones a stark reminder of the perils of their profession. The adjacent town of Scofield, which served as the supply hub for Winter Quarters, also suffered a significant decline in its wake, though it never fully became a ghost town. The silence that pervades these valleys now is a heavy one, laden with the weight of that immense loss.

As the demand for coal surged, so did the number of company towns. These were not independent municipalities but rather entities wholly owned and operated by the mining companies. From the miner’s shack to the company store, the schoolhouse to the doctor’s office, every aspect of life was managed by the coal magnates. This system, while providing essential services in remote areas, also exerted immense control over the workers. Towns like Standardville, Kenilworth, and Hiawatha sprang up, meticulously planned and efficiently run.

Standardville, founded in 1912 by the Standard Coal Company, was once considered one of Utah’s most modern coal camps. It boasted electricity, indoor plumbing, a large company store, a school, and even a gymnasium. For a time, it was a model community, home to hundreds of families. Miners toiled deep underground, extracting coal that fueled homes and industries across the West. An old newspaper clipping from the 1920s might boast of Standardville’s "unparalleled prosperity and progressive spirit." But its fate was tied directly to the fortunes of the coal market. When the Standard Coal Company ceased operations in the late 1950s, the town quickly emptied. Today, a few concrete foundations, rusted pipes, and the remnants of the old company store are all that bear witness to its vibrant past.

Kenilworth, established in 1906 by the Independent Coal and Coke Company, followed a similar trajectory. Known for its extensive underground workings and a surface plant that processed thousands of tons of coal daily, Kenilworth was a bustling hub. Like Standardville, it offered amenities to attract and retain workers. Yet, as mechanization increased and the demand for coal declined, particularly with the advent of natural gas and oil, its population dwindled. By the 1960s, it was largely deserted, its buildings eventually razed to prevent vandalism, leaving only faint scars on the landscape.

Hiawatha, another significant company town founded by the United States Fuel Company in 1911, was unique for its ethnically diverse population and its impressive scale. It had multiple mines, a large tipple, a hospital, and even a baseball field. For decades, it was a beacon of employment in the region. However, the same forces of economic decline that impacted its neighbors eventually caught up with Hiawatha. While a few structures and residences remain today, the once-thriving heart of the town is a shadow of its former self, its main streets now quiet pathways to overgrown ruins.

The Unforgiving Hand of Progress and Nature

The decline of Carbon County’s ghost towns was a complex interplay of factors. The most significant was the changing energy landscape. The widespread adoption of natural gas, oil, and eventually nuclear and renewable energy sources dramatically reduced the demand for coal. What coal was still needed could be extracted more efficiently and with fewer workers due to advancements in mining technology. Machines replaced men, leading to mass layoffs and the exodus of families seeking work elsewhere.

Labor disputes and strikes, which were common throughout the early 20th century in these company-controlled environments, also played a role. Miners, often living in substandard conditions and paid in company scrip redeemable only at the company store, frequently organized to demand better wages and safer working conditions. These sometimes violent confrontations, while occasionally leading to improvements, also created instability and hardship for the communities.

Natural disasters, beyond the 1900 explosion, also contributed to the impermanence of these settlements. Flash floods, rockslides, and harsh winters made life precarious, forcing some smaller, more remote camps to close prematurely. The very ruggedness of the terrain that protected the coal also made sustained human habitation a constant battle against the elements.

The Allure of the Abandoned

Today, the ghost towns of Carbon County hold a profound allure for historians, photographers, and curious travelers. There’s a tangible sense of stepping back in time, a quiet reverence for the lives once lived here. Visitors might stumble upon:

- Rusted mining equipment: Haunting relics of heavy industry, slowly succumbing to the elements.

- Concrete foundations: The skeletal remains of homes, stores, and community buildings, now overgrown with sagebrush and tumbleweeds.

- Cemeteries: Often the best-preserved part of a ghost town, with weathered headstones telling tales of diverse origins, short lives, and tragic ends.

- Faint traces of roads or rail lines: Pathways that once pulsed with activity, now barely discernible.

- Mine portals: Dark, foreboding openings into the earth, sealed off for safety but hinting at the vast underground networks where men toiled.

One might imagine a seasoned local historian, perhaps a descendant of a Carbon County miner, saying, "You can feel the ghosts here, not in a spooky way, but like echoes of hard work and deep community. Every piece of rusted metal tells a story if you listen closely enough." These sites are open-air museums, demanding imagination to fill in the missing pieces. The wind becomes the voices of children playing, the creaking of timbers becomes the rumble of a coal cart, and the silence is punctuated by the phantom whistle of a distant train.

While some towns, like Helper, managed to adapt and survive, shedding their company-town skin to become independent municipalities, many others faded into the landscape. Helper, often referred to as the "Hub of Carbon County," served as a crucial railroad junction and supply center. Its ability to diversify beyond direct mining operations allowed it to weather the decline of its neighbors, serving as a living reminder of the era while its once-thriving peers became spectral figures.

Lessons from the Dust

The ghost towns of Carbon County are more than just ruins; they are powerful historical markers. They remind us of the immense human cost of industrial progress, the precarious nature of economic booms, and the extraordinary resilience of those who sought a better life in challenging circumstances. They illustrate the rapid pace of technological change and its profound impact on communities.

These desolate places also serve as a poignant reflection on our relationship with the land and its resources. They underscore the cyclical nature of human endeavors – the relentless search for new resources, the creation of vast infrastructures, and their eventual abandonment when the resource is depleted or demand wanes.

As the sun sets over the red rock canyons, casting long shadows across the remains of Standardville or Hiawatha, the silence deepens. It’s a silence that speaks volumes, carrying the weight of a century of dreams, disasters, and an unwavering human spirit. The ghost towns of Carbon County are not merely forgotten places; they are silent sentinels, forever whispering their tales of a bygone era, urging us to remember the lives etched into the very fabric of Utah’s coal country. They are a profound and enduring mystery, waiting for those who pause long enough to listen to their echoes.