Echoes in the Cypress: Fort Cooper and the Enduring Ghosts of Florida’s Second Seminole War

In the heart of Florida’s Citrus County, where the whisper of wind through cypress trees now dominates the soundscape, lies a place steeped in a forgotten, yet vital, chapter of American history: Fort Cooper. A temporary bastion forged in the brutal crucible of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842), this unassuming historical site, now a state park, offers a poignant window into a conflict that shaped Florida and left an indelible mark on the nation’s conscience. Far from the grand, stone fortresses of legend, Fort Cooper was a crude, hastily constructed outpost, yet its story is one of resilience, strategic necessity, and the profound human cost of expansion.

The very existence of Fort Cooper is inextricably linked to the Second Seminole War, a conflict born from a collision of cultures and an insatiable hunger for land. Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the U.S. government sought to relocate all Native American tribes east of the Mississippi River to territories in the west. In Florida, this policy targeted the Seminole people, a diverse group descended from Creek Indians who had migrated south, as well as runaway slaves who found refuge among them. Treaties, often signed under duress or by unrepresentative factions, called for their removal, but the majority of Seminoles, led by charismatic figures like Osceola and Micanopy, vehemently refused to abandon their ancestral lands and the unique, interwoven culture they had built in the Florida wilderness.

The war ignited in December 1835 with the Dade Massacre, a devastating ambush that saw nearly all of Major Francis L. Dade’s 100-man command wiped out by Seminole warriors. This event galvanized public opinion and signaled the beginning of a brutal, protracted guerrilla war unlike any the U.S. Army had ever faced. Florida’s dense swamps, thick hammocks, and labyrinthine waterways became the Seminoles’ formidable allies, turning the sun-baked peninsula into a strategic nightmare for the conventional American forces.

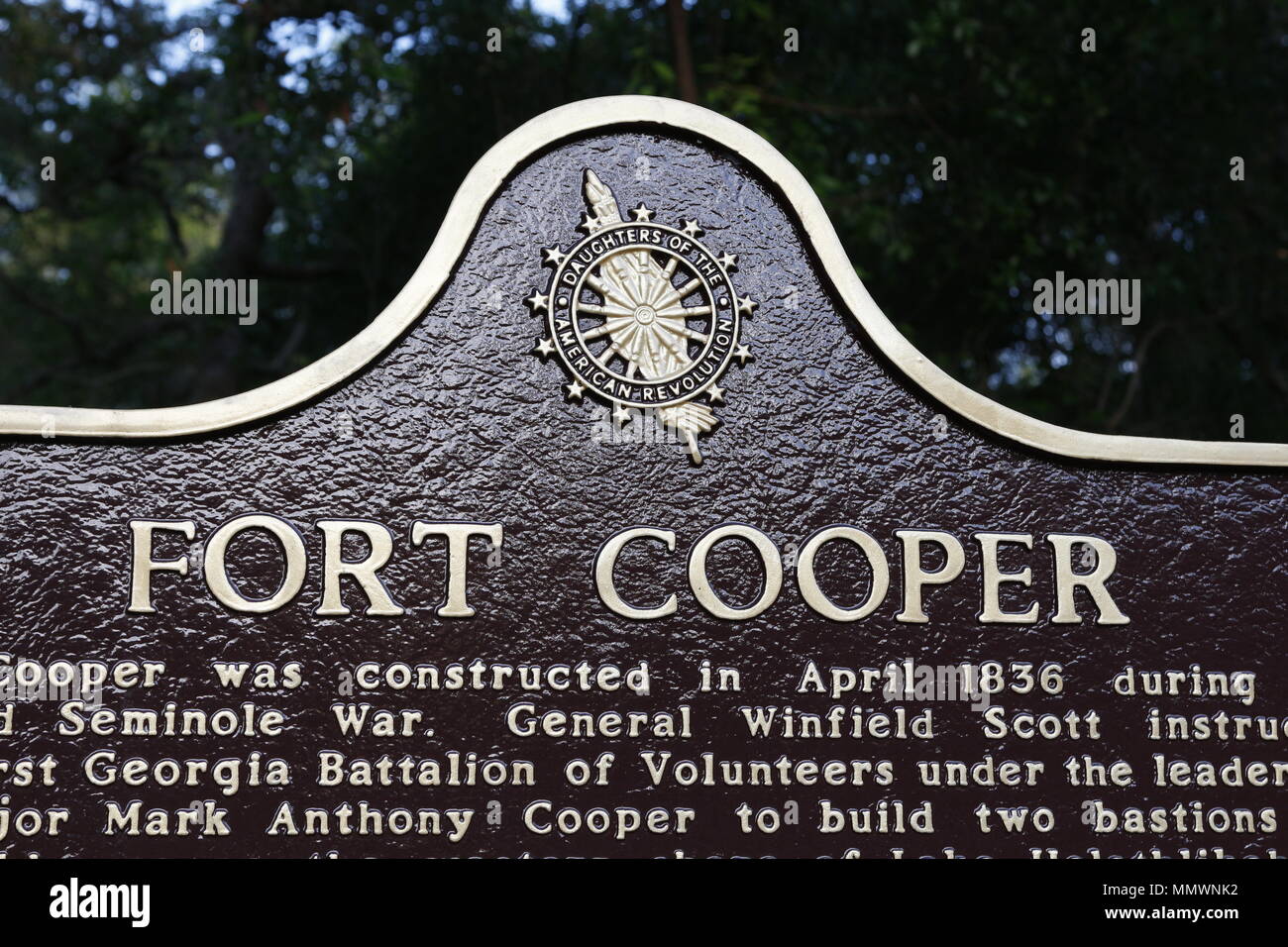

It was into this volatile landscape that Fort Cooper was born. In the spring of 1836, Major G.W. Cooper of the Georgia Volunteers, under the command of General Winfield Scott, was tasked with establishing a supply depot and defensive position deep within Seminole territory. The chosen site, near the picturesque Lake Holathlikaha, was strategically vital. It offered access to water, a relatively defensible position on higher ground, and served as a crucial link in the chain of forts being established to contain and track the elusive Seminole warriors.

Constructing a fort in the Florida wilderness was a Herculean task. Imagine soldiers, many unaccustomed to the harsh subtropical climate, toiling under a relentless sun, battling swarms of mosquitoes and other biting insects, and constantly wary of unseen Seminole eyes. They felled cypress and pine trees, stripping bark and shaping logs to form a rectangular stockade. Within its walls, crude barracks, a small hospital, a powder magazine, and a blockhouse for elevated defense were erected. It was not a place of comfort, but of stark necessity, designed for survival and projection of military power.

Life within Fort Cooper was a grueling existence. The pervasive heat and humidity were constant companions, and disease, rather than direct combat, often proved the more formidable enemy. Malaria, dysentery, and other fevers ravaged the ranks, decimating units far more effectively than any Seminole arrow or musket ball. Food supplies were often meager, consisting of salt pork, hardtack, and whatever game could be hunted or foraged from the surrounding, often hostile, environment. The constant vigilance required to guard against surprise attacks took a heavy toll on morale. Sentries peered into the dense foliage, their nerves frayed, knowing that the Seminoles’ mastery of camouflage and silent movement meant danger could emerge from any shadow.

While Fort Cooper did not witness any major pitched battles, it was a site of frequent skirmishes and tense patrols. Soldiers venturing out for reconnaissance, to gather supplies, or to pursue Seminole bands often found themselves ambushed. The Seminoles, adept at hit-and-run tactics, would strike swiftly and vanish back into the swamp, leaving the American forces frustrated and demoralized. These encounters, though perhaps small in scale, highlighted the brutal nature of the conflict and the Seminoles’ unwavering determination.

From the Seminole perspective, Fort Cooper, like all the American forts, was an unwelcome intrusion, a symbol of the encroaching world that sought to dispossess them. Their resistance was not an act of wanton aggression but a desperate fight for their very existence, for their homes, their culture, and their sacred ancestral lands. Their knowledge of the terrain, their resilience, and their ability to live off the land allowed them to wage a war that confounded and infuriated the technologically superior U.S. Army for seven long years. It was a testament to their spirit that this small, determined people could hold off the might of a burgeoning nation for so long.

Fort Cooper’s active service was remarkably brief. By the summer of 1836, the focus of the war had shifted further south, and the need for a major supply depot at Lake Holathlikaha diminished. The fort was abandoned, its timbers left to the mercy of the elements and the relentless Florida wilderness. For decades, it faded into the verdant embrace of the ecosystem, its purpose obscured by time and encroaching vegetation. Its memory persisted only in military records and the fading oral traditions of the region.

It was only through the dedication of local historians, archaeologists, and the foresight of state park initiatives that Fort Cooper began its journey back from obscurity. In the latter half of the 20th century, archaeological investigations began to pinpoint the fort’s exact location, unearthing remnants of its original structure and artifacts that spoke of the lives lived and lost within its walls. These efforts culminated in the establishment of Fort Cooper State Park, a testament to the importance of preserving even the most ephemeral chapters of history.

Today, Fort Cooper State Park is a sanctuary where history and nature intertwine. Visitors can explore a meticulously reconstructed portion of the fort, offering a tangible sense of what the outpost might have looked like in 1836. Interpretive signs provide context, detailing the fort’s role, the challenges faced by its inhabitants, and the broader narrative of the Second Seminole War. "It’s more than just a fort," explains Sarah Miller, a park ranger at Fort Cooper State Park. "It’s a place where you can truly connect with the struggles of the past. You stand here, surrounded by the same natural beauty and the same challenges of the climate, and you can almost hear the echoes of the soldiers and the Seminoles who once walked this land."

Beyond the historical reconstruction, the park offers a rich natural experience. Miles of hiking trails wind through ancient oak hammocks, pine flatwoods, and along the shores of Lake Holathlikaha, providing opportunities for birdwatching, wildlife viewing, and peaceful contemplation. Alligators glide silently through the waters, ospreys soar overhead, and deer graze in the clearings – a vibrant ecosystem that mirrors the one that existed during the war, albeit without the constant threat of human conflict. The annual Fort Cooper Days festival brings history to life with reenactments, demonstrating military drills, camp life, and Seminole cultural presentations, bridging the gap between past and present for new generations.

The enduring legacy of Fort Cooper lies not in its physical grandeur, for it had none, nor in being the site of a decisive battle, for it wasn’t. Its significance is more profound and subtle. It serves as a powerful reminder of the human cost of expansion, the brutal realities of frontier warfare, and the unwavering spirit of those who fought to defend their homes. It tells a story of strategic imperatives, environmental challenges, and the stark contrast between two cultures locked in a desperate struggle.

Fort Cooper, then, is more than just a collection of reconstructed logs and interpretive signs. It is a portal to a pivotal, often painful, chapter of American history. It invites us to reflect on the complexities of national identity, the tragic consequences of forced displacement, and the enduring resilience of both the land and its people. As the cypress trees continue to stand guard over Lake Holathlikaha, their silent witness to centuries of change, Fort Cooper ensures that the echoes of Florida’s Second Seminole War, and the profound lessons they hold, will not be forgotten. It is a testament to the idea that even the smallest, most temporary outposts can hold immense historical weight, offering invaluable insights into the forces that shaped a nation.