Echoes in the Desert: The Forgotten Frontier of Presidio San Bernardino

In the rugged, sun-baked southeastern corner of Arizona, where the Chiricahua Mountains pierce the sky and the border with Mexico is a mere whisper across the vast Chihuahuan Desert, lies a landscape steeped in a history few remember. Here, amidst mesquite and creosote, on the banks of a life-giving cienega, stand the ghostly echoes of Presidio San Bernardino. It was a place of ambition and despair, a bold declaration of Spanish colonial power at the very edge of its empire, and a poignant testament to the ephemeral nature of human endeavor against the relentless forces of nature and conflict.

Today, the site is part of the Leslie Canyon National Wildlife Refuge, a sanctuary for endangered species and a haven of biodiversity. But beneath the tranquil surface, buried under centuries of dust and forgotten by most, lie the foundations of a fort that was once a critical, if short-lived, component of Spain’s grand strategy to control its northern frontier. Its story is one of audacious vision, brutal realities, and ultimate abandonment, offering a unique window into the trials of frontier life in 18th-century North America.

The Grand Strategy: Spain’s Presidio System

To understand Presidio San Bernardino, one must first grasp the broader context of the Spanish presidio system. Far from being mere military outposts, presidios were the lynchpins of Spanish colonial expansion and defense. They were strategic fortifications, often built around a central plaza, housing soldiers, their families, artisans, and sometimes even indigenous allies. Their primary functions were to protect mission settlements, secure trade routes, and, crucially, to assert Spanish sovereignty over vast, often hostile, territories.

By the late 18th century, Spain’s hold on its northern frontier, particularly in what would become Arizona, was tenuous. Constant raids by Apache and other indigenous groups threatened Spanish settlements and prevented effective colonization. The Spanish Crown, under King Charles III, launched a series of reforms aimed at strengthening its defenses. This initiative, often referred to as the "New Regulations of 1772," called for a more integrated chain of presidios stretching across the northern borderlands, from the Gulf of California to Texas.

It was into this strategic framework that Presidio San Bernardino was conceived.

Birth on the Border: A Bold Declaration of 1776

The year 1776 resonates deeply in North American history, primarily for events far to the east. Yet, thousands of miles away, in the remote Arizona desert, another act of sovereignty was being declared. It was in this year that Hugo O’Conor, an Irish officer in the Spanish army known as "The Red Captain" due to his ruddy complexion and fiery temperament, personally selected the site for Presidio San Bernardino. O’Conor, then Inspector General of the Interior Provinces, was instrumental in implementing the New Regulations. His vision was to establish a strong defensive line against the Apaches, securing the crucial overland routes to Sonora and New Mexico.

The chosen location was strategic: a vast, fertile cienega (wetland) fed by natural springs, providing abundant water and pasture in an otherwise arid landscape. This cienega, the headwaters of the San Bernardino River, was a magnet for wildlife and, consequently, for the Apache bands who hunted them. Establishing a presidio here was a direct challenge to their traditional hunting grounds but offered a vital resource for Spanish forces.

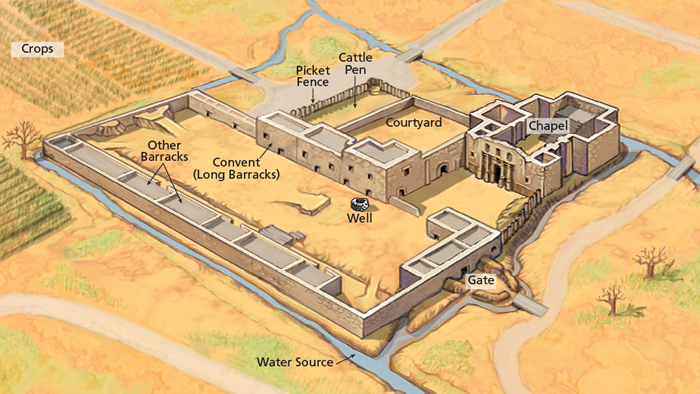

Construction began, likely in 1776 or shortly thereafter, under the supervision of Captain Pedro de la Page. The presidio was laid out as a square, approximately 200 feet on each side, with adobe walls, defensive towers (baluartes) at the corners, and an interior plaza. Barracks, a chapel, a commandant’s house, and other essential structures would have been built within its protective confines. For the soldiers and their families, San Bernardino was meant to be a permanent home, a bastion of Spanish culture and authority in the wilderness.

Life on the Edge: The Brutal Realities of Frontier Existence

Life at Presidio San Bernardino was anything but easy. The isolation was profound. The nearest Spanish settlements, like Tucson or Janos (in modern-day Chihuahua), were weeks away by horseback, through dangerous terrain. Supplies were scarce, often delayed, and always expensive. The soldiers, primarily mestizos and indigenous auxiliaries, were poorly paid, if at all, and their uniforms were often ragged.

Their daily routine was a relentless grind of drills, patrols, and the constant vigilance against Apache raids. "The desert offered no quarter," remarked one historian, encapsulating the harsh environment. "Every journey was a risk, every sunrise a potential battle." The soldiers were not just guardians; they were farmers, builders, hunters, and often their own doctors. Disease, hunger, and the psychological toll of constant threat were as formidable adversaries as any raiding party.

Despite the hardships, the presidio represented a vibrant, if precarious, community. Families lived within its walls, children were born, and the rhythms of Spanish life, including religious observances and social customs, were maintained as best as possible. It was a testament to human resilience, an attempt to replicate the familiar world in an utterly alien environment.

A Short-Lived Dream: Decline and Abandonment

The grand vision for Presidio San Bernardino, however, was destined for a short and troubled existence. Despite its strategic location, the fort faced insurmountable challenges. The Apache resistance proved fiercer and more relentless than anticipated. While the presidio offered a measure of protection, it also served as a focal point for conflict, drawing attacks rather than completely deterring them.

Perhaps the most significant factor in its demise was the shifting political and economic landscape of the Spanish Empire. Resources were continually stretched thin, diverted to more pressing concerns elsewhere. By the turn of the 19th century, Spain’s grip on its vast American colonies was loosening. Mexico’s independence movement was gaining momentum, culminating in 1821. With the new Mexican government focused on consolidating its power and dealing with internal strife, the remote and costly presidios of the far north became a low priority.

San Bernardino was among the first casualties of this neglect. By the early 1800s, perhaps as early as 1790-1800, and certainly by 1821, it had been effectively abandoned. The adobe walls, once a symbol of Spanish power, began to crumble under the harsh desert sun and the infrequent but torrential rains. The wind became its only resident, whistling through empty doorways where soldiers once stood guard. The dream of a permanent Spanish presence at San Bernardino dissolved back into the desert from which it had briefly emerged.

From Ruins to Refuge: Rediscovery and Preservation

For decades, even centuries, the ruins of Presidio San Bernardino lay largely forgotten, a faint whisper in the vastness of the Arizona desert. The land passed through various hands, notably becoming part of the famous Slaughter Ranch in the late 19th century, owned by legendary cattleman John Horton Slaughter. Slaughter himself was said to have used some of the presidio’s crumbling adobe walls as foundations for his own ranch buildings, further integrating the historical layers of the landscape.

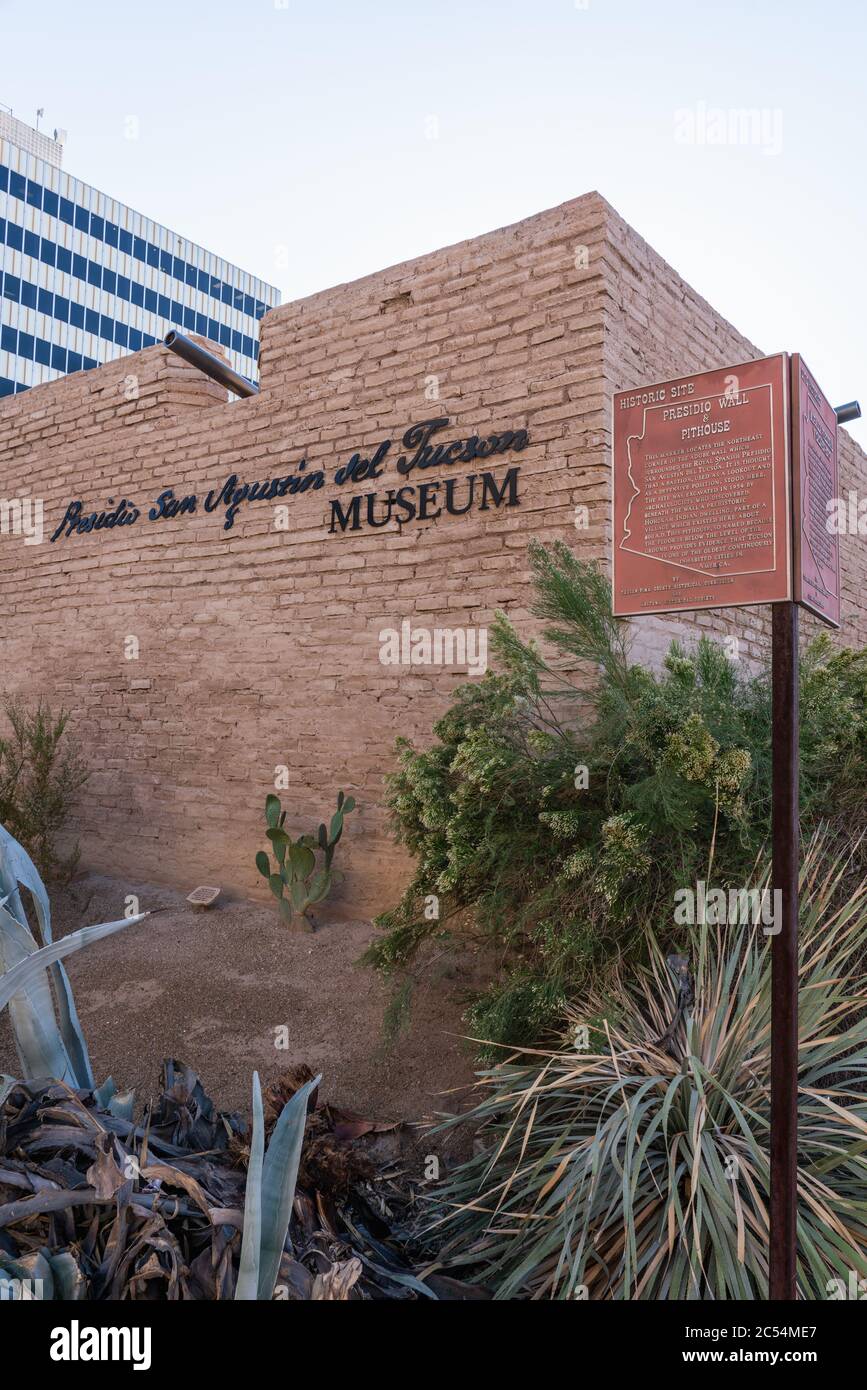

It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that serious archaeological interest in the site began to emerge. Researchers recognized the importance of San Bernardino as one of the best-preserved, albeit ruined, examples of a late-18th-century Spanish presidio in Arizona. Archaeological excavations, particularly those led by the National Park Service and other institutions, have since revealed much about the presidio’s layout, construction, and the daily lives of its inhabitants.

Artifacts unearthed include fragments of Spanish pottery, military buttons, musket balls, and tools, offering tangible links to the past. These finds provide invaluable insights into the material culture of the frontier soldiers and their families, shedding light on their diet, their trade networks, and their constant struggle for survival. The archaeological work continues to piece together the narrative of this remote outpost, adding detail and nuance to its brief but significant history.

Today, the site is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as part of the Leslie Canyon National Wildlife Refuge, which encompasses the critical San Bernardino Cienega. This modern designation highlights a continuity with the past: the very water resources that drew the Spanish to establish a presidio here are now vital for the survival of endangered fish species and migratory birds. The historical importance of the presidio is recognized, and efforts are made to protect the fragile ruins and interpret their significance for visitors.

The Enduring Legacy

Presidio San Bernardino, despite its short lifespan, remains a powerful symbol. It represents the ambitions and challenges of European colonialism in North America, the complex interactions between different cultures, and the enduring power of the natural world. It stands as a physical manifestation of a crucial, often overlooked, chapter in Arizona’s history – a time when the desert was a battleground, a crucible where empires clashed and individual lives were forged in the fires of hardship.

Walking among the subtle depressions and faint outlines that mark the former walls of the presidio today, one can almost hear the echoes of a distant past: the clatter of Spanish sabers, the shouted commands, the quiet murmur of a soldier’s prayer, and the ever-present rustle of the wind, carrying the ghosts of a forgotten frontier. Presidio San Bernardino is more than just a ruined fort; it is a profound historical marker, reminding us that even in the most desolate landscapes, human stories of courage, struggle, and eventual relinquishment leave an indelible mark on the land. It stands as a silent sentinel, guarding the memory of a pivotal moment when a distant empire tried, and ultimately failed, to tame the wild heart of the Arizona desert.