Echoes in the Earth: The Enduring Legacy of Kanaka Jack’s Mine, California

Deep within California’s Sierra Nevada foothills, where the whisper of pine trees carries the weight of history, lie countless scars etched into the earth. These are not just geological formations but testaments to an era of unbridled ambition, backbreaking labor, and the relentless pursuit of gold. Among the myriad of forgotten diggings and faded claims, a name like "Kanaka Jack’s Mine" stands out, not for its singular fame, but for its profound symbolic power. It embodies the global tapestry of the California Gold Rush, the environmental cost of unchecked extraction, and the often-overlooked stories of those who chased the golden dream from across oceans.

Kanaka Jack’s Mine, like so many others, is less a monument and more a ghost – a collective memory of the rugged individualism and collective struggle that defined mid-19th century California. To understand its legacy is to delve into the very heart of the Gold Rush, to explore the lives of the "49ers" and their diverse origins, and to confront the lasting impact of humanity’s insatiable hunger for wealth.

The Golden Allure: A World Converges on California

The year 1848 marked a seismic shift in American history. James Marshall’s discovery of gold flakes at Sutter’s Mill ignited a global frenzy, transforming California from a sparsely populated frontier into a magnet for dreamers, desperadoes, and entrepreneurs from every corner of the globe. From Europe, South America, Asia, and the Pacific Islands, people poured into the burgeoning territory, driven by the siren call of instant riches. This was the "Mother Lode," a vast belt of gold-bearing quartz veins stretching some 120 miles through the Sierra Nevada, promising untold wealth to those brave or desperate enough to claim it.

The journey itself was an epic undertaking – by sea around Cape Horn, by treacherous land routes across the continent, or via the Isthmus of Panama. Those who arrived found a landscape of rugged beauty and stark contrasts, where fortunes could be made and lost in a single day, and where the rule of law was often supplanted by the rough justice of the mining camps. It was a chaotic, vibrant, and often brutal society, forged in the crucible of gold fever.

Who Was Kanaka Jack? The Global Face of the Gold Rush

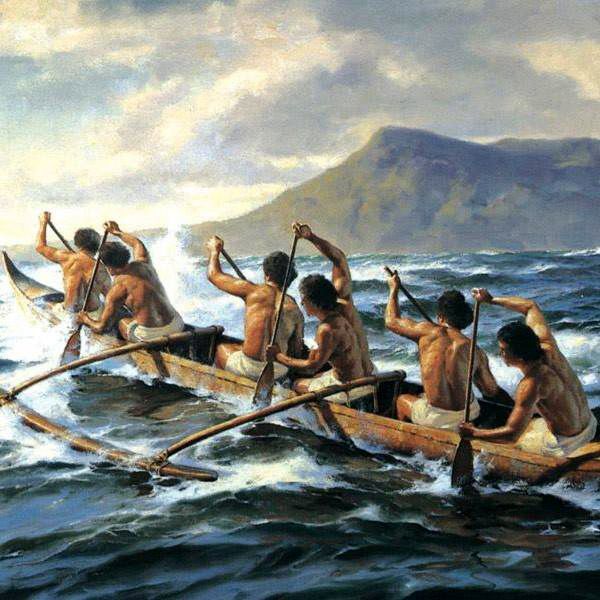

The name "Kanaka Jack" itself offers a crucial window into this diverse historical landscape. "Kanaka" was a term, often used with varying degrees of respect and derision, for Pacific Islanders, particularly Hawaiians, who played a significant but often unacknowledged role in the early development of the American West. Long before the Gold Rush, Hawaiians were skilled sailors, whalers, and laborers, frequently employed on ships navigating the Pacific. Many had settled along the Pacific Northwest coast, working in the fur trade and timber industries.

When news of gold reached the Hawaiian Islands, it sparked its own mini-rush. Lured by the promise of quick wealth and established trade routes, thousands of Hawaiians made their way to California. They brought with them unique skills, a strong work ethic, and a resilience born of their maritime heritage. They joined the melting pot of cultures in the mining camps, working alongside Americans, Chinese, Mexicans, Chileans, and Europeans. Kanaka Jack, therefore, represents not just one individual, but the collective experience of these often-marginalized islanders who contributed to the California dream.

"The Gold Rush wasn’t just an American story; it was a global phenomenon," explains Dr. Eleanor Vance, a historian specializing in trans-Pacific migration during the 19th century. "Figures like ‘Kanaka Jack’ remind us that people came from everywhere, bringing their cultures, their labor, and their hopes. They faced the same hardships as other miners, but often also the additional burden of racial prejudice and cultural misunderstanding."

While the specific details of Kanaka Jack’s life remain shrouded in the mists of time – as do those of countless other independent miners – his mine likely resembled many small-scale operations of the era. It could have been a placer mine, where gold was extracted from riverbeds using pans, sluice boxes, or rocker cradles. Or, as the easier surface gold dwindled, it might have transitioned to hard-rock mining, digging shafts and tunnels into quartz veins, a far more dangerous and labor-intensive endeavor.

The Brutality of the Diggings: Life at the Mine

Life at a mine like Kanaka Jack’s was a relentless grind. Days began before dawn, fueled by meager rations and the constant hope of striking it rich. The work was physically demanding: digging, shoveling, blasting, and hauling heavy loads of earth and rock. Accidents were common – cave-ins, explosions, and injuries from primitive tools. Disease, often exacerbated by poor sanitation and nutrition, swept through the camps with deadly efficiency. Cholera, dysentery, and scurvy claimed more lives than any claim dispute.

The landscape around the mine would have been a hive of activity, constantly reshaped by human hands. Trees were felled for timber to shore up tunnels and build cabins. Rivers were diverted, their beds churned over in search of elusive flakes. The air would have been thick with dust, the clang of picks, the shouts of men, and the ever-present hum of mosquitoes.

As the surface gold became scarcer, more advanced and destructive methods emerged. Hydraulic mining, though not likely practiced by individual miners like Kanaka Jack due to its immense capital requirements, dramatically altered the landscape of the Mother Lode. It involved directing powerful jets of water at hillsides to wash away gold-bearing gravel, leaving behind colossal scars known as "monitor pits." While incredibly efficient, it ravaged the environment, silting up rivers, destroying agricultural land downstream, and creating vast, barren landscapes that persist to this day. This method, eventually banned by the landmark Sawyer Decision of 1884, became a symbol of the environmental recklessness of the era.

Boom, Bust, and the Shifting Sands of Fortune

For every miner who struck it rich, hundreds toiled in vain. The vast majority of those who came to California seeking their fortune found only hardship, disappointment, and debt. Boomtowns sprang up overnight around promising claims, only to be abandoned just as quickly when the gold ran out. These ephemeral settlements, with their saloons, gambling dens, and makeshift stores, were microcosms of the Gold Rush dream – fleeting, intense, and often ending in desolation.

The social fabric of these camps was complex. While a veneer of equality sometimes existed in the initial rush, racial and ethnic tensions simmered beneath the surface. The "Foreign Miner’s Tax," aimed primarily at Chinese and Mexican miners but often applied to any non-white individual, was a discriminatory measure designed to protect the interests of American miners and extract revenue from "foreigners." Hawaiians, like Kanaka Jack, often faced similar prejudices, navigating a landscape where their labor was valued but their presence was often unwelcome.

"The dream of California gold was universal, but the reality of access and opportunity was anything but," notes Dr. Vance. "The laws and social norms of the time often ensured that the hardest labor and the least reward fell to those who were not considered ‘American.’"

The Lingering Scars: Environmental and Historical Legacy

Today, the physical remnants of Kanaka Jack’s Mine, like many small diggings, are likely subtle – a collapsed shaft, a spoil pile slowly being reclaimed by nature, a faint indentation where a cabin once stood. The true legacy, however, is far more profound and widespread.

Environmentally, the Gold Rush left an indelible mark. The hydraulic mining operations created monumental landscapes of erosion and sediment, forever altering river systems and ecosystems. Even smaller-scale placer mining contributed to siltation and habitat destruction. The long-term effects on water quality, biodiversity, and land stability are still being felt and studied today. The "ghost forests" of ancient trees buried under layers of mining debris stand as stark reminders of the massive scale of human intervention.

Historically, the Gold Rush cemented California’s place in the American imagination and economy. It accelerated statehood, fueled westward expansion, and laid the groundwork for the state’s incredible growth. But it also left a legacy of displacement for indigenous populations, environmental devastation, and a complex narrative of racial and ethnic relations that continues to inform Californian identity.

Remembering the Unsung: A Call for Preservation and Understanding

Kanaka Jack’s Mine, though perhaps not a prominent historical landmark, serves as a powerful symbol. It represents the countless untold stories of the Gold Rush, particularly those of the diverse populations who flocked to California from across the globe. It reminds us that history is not just about famous figures and grand events, but also about the cumulative impact of ordinary people pursuing extraordinary dreams.

Today, efforts are underway to preserve and interpret the broader history of the Gold Rush. Historical societies, museums, and state parks work to protect remnants of mining camps, interpret the stories of all who participated, and educate the public about the environmental consequences of that era. These efforts seek to move beyond the romanticized image of the lone prospector and embrace the full, complex, and often harsh reality of the period.

The legacy of Kanaka Jack’s Mine, therefore, is not just about gold, but about human ambition, resilience, and the sometimes-devastating cost of progress. It invites us to look closer at the scarred earth, to listen to the whispers of history carried on the wind, and to remember the faces of all those who, like Kanaka Jack, sought their fortune in the golden hills of California, leaving behind a story as rich and complex as the veins of quartz they tirelessly pursued. It stands as a timeless reminder that even in the pursuit of wealth, there are always deeper treasures to be found in the understanding of our shared past.