Echoes in the Earth: The Enduring Mystery of the Mogollon People

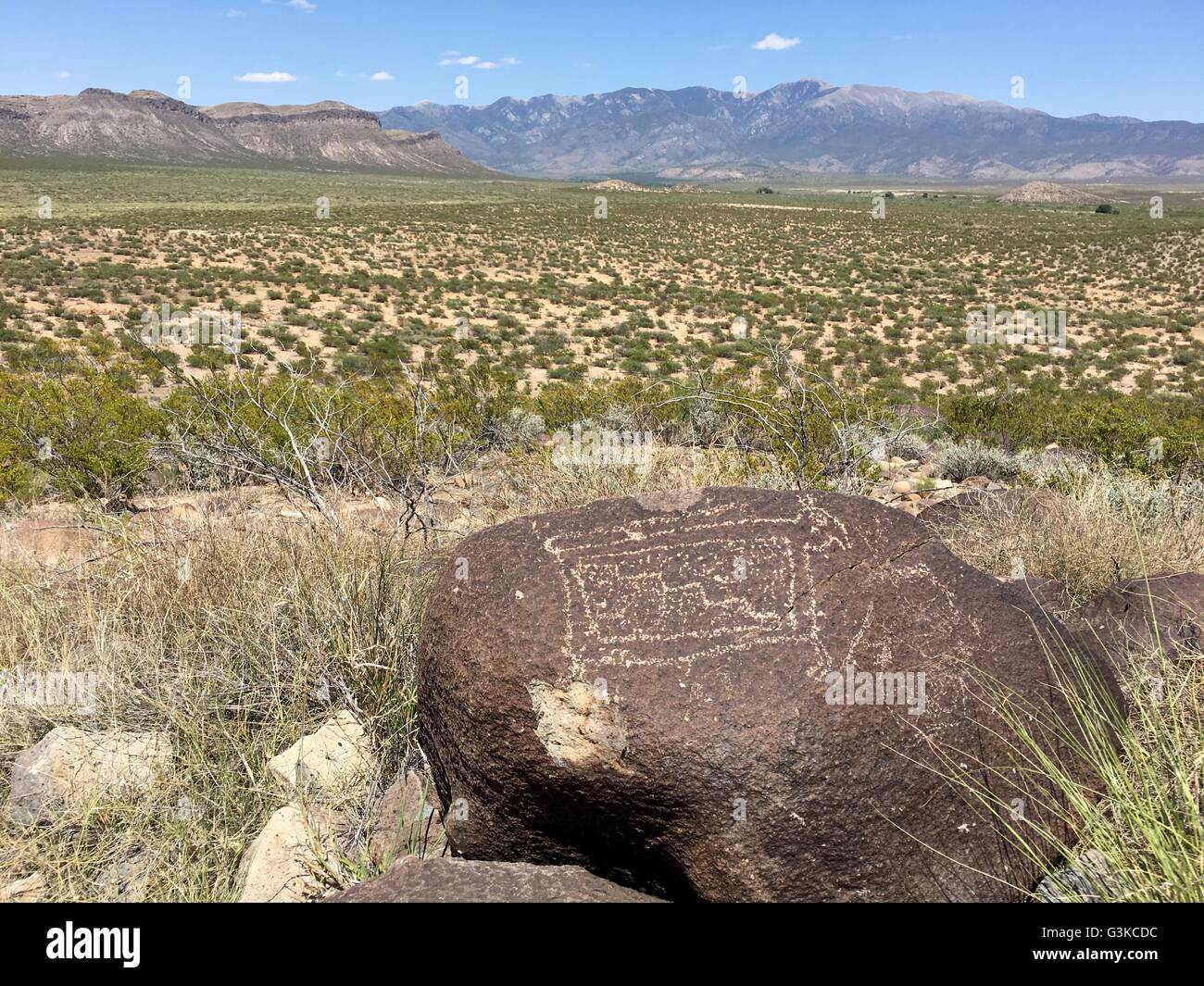

In the vast, sun-drenched landscapes of the American Southwest, where time seems to stretch infinitely across canyons and mesas, the echoes of forgotten cultures whisper on the wind. Among the most enigmatic of these ancient peoples are the Mogollon, a sophisticated and resilient society that thrived for over a millennium before their distinct cultural identity faded into the annals of prehistory around 1450 AD. Their story, pieced together painstakingly by archaeologists from fragments of pottery, remnants of dwellings, and the faint imprints of their lives on the earth, is one of ingenuity, adaptation, and a profound, enduring mystery.

The Mogollon culture emerged in the mountainous regions of what is now southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, as well as parts of northern Chihuahua and Sonora in Mexico, roughly around 200 AD. They are typically categorized alongside the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) to their north and the Hohokam to their west as one of the three major prehistoric cultural traditions of the American Southwest. Yet, unlike their more famous neighbors, the Mogollon often feel like the quiet achievers, their legacy less monumental in scale but no less intricate in detail.

The Cradle of Culture: From Hunter-Gatherers to Farmers

The earliest Mogollon people were primarily hunter-gatherers, skillfully exploiting the diverse resources of their environment. They hunted deer, rabbits, and other small game, and gathered a wide array of wild plants, berries, and nuts. However, by the early centuries AD, a pivotal shift occurred: the adoption of agriculture. Maize, beans, and squash – the "Three Sisters" of Native American agriculture – became the cornerstones of their diet, allowing for more settled lifestyles and the development of permanent villages.

Their early dwellings were characteristic pit houses, structures excavated partly into the ground, providing natural insulation against the region’s extreme temperatures. These semi-subterranean homes, often circular or oval, featured a central hearth and a roof supported by wooden posts and covered with brush and earth. As time progressed, these pit houses became more complex, sometimes incorporating antechambers or specialized storage areas, reflecting a growing architectural sophistication and a deeper commitment to settled community life.

"The Mogollon were masters of adaptation," notes Dr. Sarah Miller, an archaeologist who has spent decades studying the region. "They weren’t just surviving; they were thriving in a challenging environment, learning to coax life from the soil and construct durable homes with the materials at hand. Their early pit houses are a testament to human ingenuity and a deep understanding of their local ecology."

Adapting to the Arid Lands: Resourcefulness and Community

Life for the Mogollon revolved around their relationship with the land and the rhythms of the seasons. Their agricultural practices were sophisticated, often involving small-scale irrigation systems to channel precious water to their crops. Beyond farming, they continued to hunt and gather, maintaining a diversified economy that buffered them against agricultural failures. This dual reliance on cultivated crops and wild resources highlights their pragmatism and resilience.

Mogollon communities were generally small, consisting of a few dozen to a few hundred people. Social structures likely emphasized cooperation and communal effort, essential for tasks like farming, hunting, and constructing dwellings. While evidence for highly stratified societies is scarce, the presence of larger communal structures, such as great kivas in later periods, suggests a level of social organization and shared ritual practices. These kivas, often much larger than typical dwellings, served as gathering places for ceremonies, councils, and community events, underscoring the importance of collective identity.

Their toolkits were crafted from stone, bone, and wood, reflecting their practical needs. They produced well-made projectile points for hunting, grinding stones for processing corn, and various scraping and cutting tools. But it is in their pottery that the Mogollon truly distinguished themselves, leaving behind an artistic legacy that continues to captivate and puzzle scholars today.

The Artistic Heartbeat: The Mimbres Mogollon

While all Mogollon groups produced pottery, it is the Mimbres Mogollon, flourishing in the Mimbres Valley of southwestern New Mexico between approximately 1000 and 1130 AD, who achieved an unparalleled level of artistic expression. Their black-on-white pottery, particularly their bowls, is world-renowned for its intricate and often whimsical designs.

Mimbres bowls are characterized by striking geometric patterns, often complex and perfectly symmetrical, but also by their iconic anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures. These images depict a rich tapestry of life: humans engaged in daily activities or ritualistic poses, various animals (birds, fish, rabbits, bighorn sheep, insects), and mythical creatures that blend features of different animals. The designs are often incredibly dynamic, capturing movement and narrative in a static form.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Mimbres pottery, especially the bowls found in burial contexts, is the presence of a "kill hole" – a small, deliberately punched hole in the center of the bowl. The exact meaning of these holes remains a subject of debate among archaeologists. Some theories suggest they were ritualistically "killed" to release the spirit of the bowl, allowing it to accompany the deceased into the afterlife. Others propose they were simply practical, to "kill" the vessel to prevent looting or reuse, or to signify its ceremonial retirement. Regardless of its precise meaning, the "kill hole" adds another layer of intrigue to these already remarkable artifacts.

"The Mimbres pottery isn’t just art; it’s a window into their cosmology, their worldview, and perhaps even their deepest fears and aspirations," explains Dr. Anya Sharma, an art historian specializing in pre-Columbian cultures. "Each vessel tells a story, whether it’s about hunting, agriculture, or the spiritual connection between humans and the natural world. They possess a sophistication and narrative quality rarely seen in other contemporary Southwestern pottery traditions."

Architectural Evolution and Societal Shifts

Around 1000 AD, coinciding with the peak of Mimbres pottery production, Mogollon architecture began to shift dramatically. While pit houses remained in use, there was a gradual transition towards above-ground masonry pueblos, multi-room structures built with stone and adobe. This change may have been influenced by interactions with the Ancestral Puebloans to the north, who were renowned for their multi-story cliff dwellings and pueblos.

These larger, more complex settlements suggest a growing population and potentially more intricate social organization. Trade networks also flourished, connecting Mogollon communities with their neighbors. Mogollon pottery, shells from the Gulf of California, and other goods moved across the Southwest, indicating a vibrant exchange of ideas and resources. This period represents a high point of cultural interaction and development for the Mogollon.

The Vanishing Act: A Profound Mystery

Then, around 1450 AD, the distinct Mogollon cultural identity began to fade. Their unique pottery styles ceased, their village sites were abandoned, and their way of life, as archaeologists understand it, seemingly dissolved. Unlike the dramatic collapses of some other ancient civilizations, the "disappearance" of the Mogollon was likely a gradual, complex process, and its causes are still debated.

Several hypotheses attempt to explain this cultural transformation:

- Climate Change and Environmental Degradation: The Southwest experienced significant climatic shifts, including prolonged droughts, during the late prehistoric period. Such droughts would have severely impacted agricultural yields and water resources, making sustained settlement difficult.

- Resource Depletion: Intensive farming and increasing population pressure might have led to the depletion of local resources, forcing communities to relocate or adopt new subsistence strategies.

- Warfare and Social Unrest: While not as extensively documented as in some other regions, evidence of conflict (e.g., defensive site locations, burned villages) exists in the Southwest. External pressures or internal strife could have contributed to the breakdown of Mogollon communities.

- Assimilation and Migration: Perhaps the most widely accepted theory is that the Mogollon did not vanish but rather assimilated into neighboring, larger cultural groups, particularly the Ancestral Puebloans. As environmental and social pressures mounted, Mogollon people may have migrated to more stable regions, adopting the customs, languages, and identities of their new neighbors. Their unique cultural markers simply ceased to be produced.

- Disease: While less likely for pre-Columbian times, any outbreaks of disease could have severely impacted smaller communities.

"To speak of the Mogollon ‘disappearing’ is perhaps too simplistic," suggests Dr. Liam O’Connell, a cultural anthropologist. "Cultures don’t vanish into thin air; they transform, they merge, they adapt in ways we are only beginning to comprehend. The Mogollon’s legacy likely lives on, not in a direct lineage, but woven into the complex cultural tapestry of the modern Pueblo peoples and other indigenous groups of the Southwest."

A Legacy of Ingenuity and Art

Today, the silence of the ancient Mogollon sites speaks volumes. Their abandoned pit houses and pueblo ruins, the scattered shards of their exquisite Mimbres pottery, and the faint traces of their agricultural fields are all that remain of a people who once thrived in the heart of the Southwest. Yet, their story is far from over. Ongoing archaeological research continues to unearth new insights, slowly piecing together a more complete picture of their lives, their beliefs, and the challenges they faced.

The Mogollon remind us of the incredible resilience and adaptability of human cultures, capable of transforming landscapes, developing sophisticated art forms, and building enduring communities in demanding environments. Their ultimate fading into the larger currents of Southwestern prehistory serves as a powerful testament to the dynamic and ever-changing nature of human civilization. Though their distinct voice is now silent, the echoes of the Mogollon people resonate through the canyons and across the mesas, a timeless reminder of the rich and complex human story etched into the earth.